Delphinapterus leucas, Pallas, 1776

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6602871 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6602716 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/0A1287D0-6B7F-9030-FAD8-8CBB73DA13A0 |

|

treatment provided by |

Diego |

|

scientific name |

Delphinapterus leucas |

| status |

|

2. View Plate 21: Monodontidae

Beluga

Delphinapterus leucas View in CoL

French: Béluga / German: \WeilRwal / Spanish: Beluga

Other common names: Beluga Whale, Sea Canary, White Whale

Taxonomy. Delphinus leucas Pallas, 1776 ,

“die im Obischen Meerbusen” (= mouth of Ob River), North-eastern Siberia, Russia.

This species is monotypic.

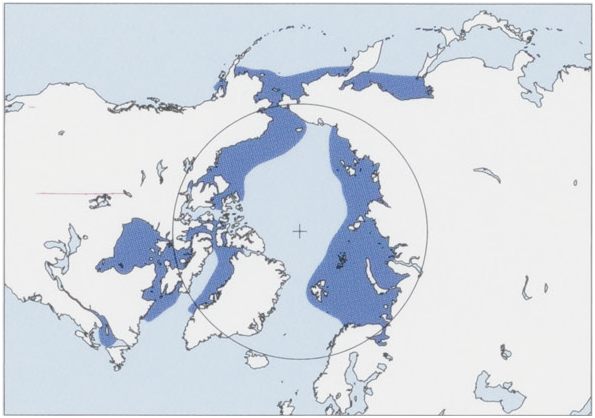

Distribution. Arctic and subarctic waters S to ¢.50° N, Greenlandic and E European populations have their S distributional limits farther to the N at c.64° N. Young Belugas occasionally stray S of their normal distribution, and they have been seen near Long Island, New York, USA, and in the Seine River, France. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Total length 300-450 cm; weight 500-1600 kg. Male Belugas are heavier and larger than females. Size varies geographically, with larger individuals in Arctic regions than in subarctic regions. Belugas are rotund, with bulging midsections when fat. They have visible neck regions, which in healthy adults and particularly males give the appearance of shoulders. Unlike most other whales, cervical vertebrae of Belugas are not fused, and they can move their head quite well, probably an adaptation to life in shallow waters and under jumbled sea ice. They have small blunt heads with short beaks, and their mouths curve upward toward the eyes. Belugas have 8-11 blunt, uniform-looking teeth on both sides of upper and lower jaws, up to 40 in total. Their rostrums have globe-like melons, lumps offatty tissue that are used as acoustic lens to focus echolocation signals. Blowhole opens behind the melon just above the eyes. Dorsal ridge runs along mid-back, starting well behind head and flattening before tailstock. Belugas are born pink, white, or gray and become slate-gray in their first month. They progressively whiten over the entire body with age. Adult Belugas are entirely white, except for edges of fins, tail flukes, and dorsal ridges, which retain some dark pigment. In spring and early summer, Belugas may appear yellow when they are shedding epidermal skin during annual molt. This is most apparent in the Hudson Bay region where skin molt is rapid. Such a rapid molt has not been observed for Belugas elsewhere and may simply be more gradual in other parts of their distribution.

Habitat. Coastal areas in summer and offshore water in open pack ice or heavier ice cover, with expanses of seawater that remain open, in winter. Thousands of Belugas may be seen in or around certain estuaries in June-September. They occupy these estuarine waters for periods that vary from a few weeks to three months, depending on latitude. Subarctic Belugas tend to remain in estuaries longer than their more northern counterparts. Belugas can form aggregations of several thousand individuals in a single estuary. In estuaries with high tidal amplitude, such as Churchill or Seal River estuaries of Canada, they move upstream to the shallowest parts of the estuary or even into the river outflow with rising tides and recede downstream with lowering tides. Females and their offspring are generally found farther upstream of the estuary or river outflow than males. In some cases, Belugas may become stranded in a tidal pool when they linger too long on an ebbing tide. Movement in and out of estuaries is not uncommon, and Belugas may use more than one estuary during summer. Function of coastal aggregations of Belugas has been the subject of much debate. It has been suggested that they use estuaries to benefit from warm water, which would promote growth of newborns during early lactation. Shallow estuaries would also serve as havens against the main predator of Belugas, the Killer Whale (Orcinus orca), when young Belugas are most susceptible to predation. Summer aggregation in estuaries also coincides with skin molt, and it has been suggested that warm and fresh water promotes rapid skin molt. Finally, in some estuaries, Belugas may find an abundance of prey fish, like capelin (Mallotus villosus), eulachon (Thaleichthys pacificus), whitefish (Coregonus sp.), or various salmon species. It is plausible that estuaries serve more than one function, and variation occurs across regions. It is noteworthy that in some regions, like Svalbard, Belugas do not occupy estuaries in summer and do not show signs of rapid molt. The need for warm water by newborn Belugas was questioned when it was shown that they have sufficient insulation at birth to withstand cold Arctic waters. It is also notable that some shallow bays used in summer or fall by Beluga herds (e.g. Millut Bay, Baffin Island, and Bethune Inlet, Devon Island) have glacial-fed river mouths and consequently their waters are colder than surrounding seawater. Some subarctic populations of Belugas (e.g. Gulf of Saint Lawrence, Cumberland Sound, Cook Inlet, and Anadyr Bay) are sedentary, remaining in or near their summer range in winter. Belugas in more northern regions spend a shorter time in estuaries than their more southern counterparts, usually confining their mass occupation to the early part of the season. These Belugas have been tracked to areas with depths of several hundred meters, where they were diving to the bottom. The difference in duration of estuarine occupation could be due to the fact that northern Belugasstill find shelter from Killer Whales in residual pack ice in summer, while in subarctic waters, where pack ice disappears earlier, Belugas can only find shelter in estuaries and shallow bays. In winter, Belugas avoid coastal fast ice and seek offshore waters, generally over banks less than 500 m deep. Their wintering areas are covered with open pack ice or, in heavier ice cover, with leads or “polynyas” (expanses of seawater that remain open in winter due to the effect of currents and winds). In these areas, Belugas frequently dive all the way to the seabed, presumably to feed.

Food and Feeding. Belugas eat a variety of pelagic and benthic fish and invertebrates. Small Arctic cod ( Boreogadus saida and Arctogadus glacialis, both Gadidae ) and Greenland halibut ( Reinhardtius hippoglossoides, Pleuronectidae ) are eaten throughout the year. Gonatid squid (Gonatus fabricii) probably are eaten mostly in winter. They also prey on fish species found in estuaries or adjacent coastal waters, such as osmerids capelin and eulachon, and salmonids, salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.), charr (Salvelinus sp.), and whitefish. During autumn migration, Belugas have been seen taking advantage of large swarms of Arctic cod and shrimps (e.g. Pandalus montagui). In winter, they are known to eat redfish ( Sebastes marinus, Sebastidae ), other shrimp species (e.g. northern shrimp, Pandalus borealis , Pandalidae ), and squid. Belugas actively feed in springtime, diving under edges of the fast ice, presumably foraging for Arctic cod and possibly for coregonid fish in some areas.

Breeding. Belugas mate in late winter or early spring, either in their winter home ranges or during migration to their summer home ranges. Females reach sexual maturity at 9-12 years, males later. Gestation is c.14 months. A single offspring is born in spring to late summer, with peaks in late June-August. Neonates are c.150 cm in length and 35-85 kg in weight at birth. Young are suckled for six months to two years, and they may remain with their mothers for several years after that. Gestation of over a year followed by a prolonged suckling period precludes having an offspring every year. A biennial birth rate is more likely for young female Belugas; with age, females tend to give birth less frequently. Overall, Beluga populations probably have an average birth rate of one young every three years, but this may vary slightly among populations. Maximum recorded age is ¢.80 years.

Activity patterns. While in estuaries, Belugas have been observed rubbing on the bottom and surfacing with mud on their heads. This behavior is thought to accelerate sloughing of molting skin in early summer. In estuaries, they are often seen spy-hopping, tail-slapping, and chasing and rubbing against each other. During these social activities, many vocalizations can be heard. Rosette formations have also been described where several Belugas quietly face each other with their bodies radiating out. Most dives in coastal areas are shallow but, when offshore, Belugas of both sexes frequently dive through the water column down to the seabed to depths of at least 500 m; some dives even go down to 800 m. Young are unable to make these deep dives and remain near the surface while their mothers forage. Adult male Belugas are capable of deeper dives; a record dive of ¢.1000 m has been measured. Both sexes make dives that last 10-25 minutes. Winter dives are longer, on average, than summer dives because of deeper seabeds in their wintering areas.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Many populations of Belugas are migratory. They alternate between large ice-covered seas in winter and summer ranges that center closer to coastal areas. Their migrations can cover 1500-4000 km between summering and wintering areas and last 2-3 months. Genetic and tracking studies document considerable diversity of mtDNA types (haplotypes), and comparisons of haplotypes suggest that Beluga populations have a strong fidelity to the areas where they summer. Chromosomal or nDNA is inherited from both parents and shows less diversity than mtDNA. This suggests that there is interbreeding between neighboring summer stocks of Belugas, presumably due to overlapping wintering ranges. Beluga populations in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, James Bay, and Cumberland Sound of Canada, Cook Inlet of Alaska, and Anadyr Bay and White Sea of Russia are non-migratory. They reside in and near large estuaries, bays, or enclosed seas throughout the year. Their summer ranges are further inshore than their winter ranges, but their seasonal ranges overlap. Belugas are presumably responding to changing ice conditions and prey availability by extending their distributions in winter. Both summer and winter home range sizes of Belugas vary with population size. Generally, small (less than 10,000 individuals), sedentary subarctic populations of Belugas have small home ranges of a few thousand to a few tens of thousand square kilometers, and larger populations (greater than 10,000 individuals), all of which are migratory, have summer and winter home ranges of 50,000-120,000 km*. Winter ranges are broader than summer ranges, presumably because Belugas occupy ice-covered waters and have to spread out more widely to find open water. Belugas often form pods of 2-10 individuals, usually segregated by sex and age: pods of females and offspring, pods of juveniles, or pods of adult males. Single individuals are usually adult males. In summer, Belugas form large mixed aggregations of several hundred to several thousand individuals in estuaries and shallow coastal bays. The largest estuarine herd on record numbered more than 7000 Belugas in Hudson Bay’s Seal River Estuary. Females and offspring are usually found farther upstream of estuaries than males, which tend to be more peripheral. Large herds are also seen in autumn and spring during migrations to and from wintering areas.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Near Threatened on The IUCN Red List, but Cook Inlet subpopulation classified as Critically Endangered. Belugas have a circumpolar distribution, with highest numbers in Canadian Arctic and Alaskan waters. A number of potential threats have been suggested for Belugas. The major concern relates to intensive hunting of small or declining populations, particularly in Canada and Greenland. Less easily quantifiable concerns are fisheries competition and bycatch, habitat loss or disturbance due to industrial activity and increased vessel traffic, environmental contaminants, and climate-induced ecosystem changes in their seasonal habitats, such as increased competition with other marine species and increased predatory pressure from Killer Whales. Numbers of Belugas worldwide are high, in excess of 150,000 individuals in total, and it is not considered threatened. Genetic information and data on the seasonal distribution of Beluga populations serve as the basis for population conservation and management around the world. There are at least 16 management units in Arctic and subarctic regions, and probably more than one-half of the units represent reproductively isolated populations. Declines of some Canadian Beluga populations (Saint Lawrence Estuary, Cumberland Sound, Eastern Hudson Bay, and Ungava Bay) have been documented, and there are proposed or enacted listings of threatened or endangered status under the Species at Risk Act (SARA) in Canada. Listing under SARA requires responsible government departments to design and implement a recovery plan to reverse the risk factors affecting the population, including protecting critical habitat. In the USA, the Alaskan Cook Inlet population of Belugas is also listed under the US Endangered Species Act, a listing that has similar requirements for recovery planning and implementation. In Greenland, the observed decline of the Beluga population that winters in Davis Strait has resulted in the establishment of new regulations on hunting of West Greenland Belugas. Populations of Belugas elsewhere in the world appear to be stable, although many Beluga populations near Russia have not been assessed. Small numbers of Belugas in the Okhotsk Sea are live-captured annually for the aquarium trade. The export of those captures from Russia 1s regulated under CITES.

Bibliography. Alvarez-Flores & Heide-Jorgensen (2004), Angliss & Outlaw (2005), Bailey & Zinger (1995), Barber & Richard (1992), Barber et al. (2001), Béland et al. (1993), Birkeland et al. (2005), Boltunov & Belikov (2002), Bourdages et al. (2002), Brennin (1992), Brennin et al. (1997), Brodie (1967 1970, 1971, 1972), Brown Gladden, Ferguson & Clayton (1997), Brown Gladden, Ferguson, Friesen & Clayton (1999), Burns & Seaman (1985), Caron & Smith (1990), COSEWIC (2004), De Guise et al. (1995), DFO (2009), Dietz et al. (1994), Doan & Douglas (1953), Doidge (1990a, 1990b, 1990c), Drinnan & Sadleir (1981), Erbe (2000), Erbe et al. (1999), Finley (1982, 1990b), Finley & Renaud (1980), Finley, Hickie & Davis (1987), Finley, Miller, Allard et al. (1982), Finley, Miller, Davis & Greene (1990), Fish & Mowbray (1962), Fraker (1980), Fraker et al. (1979), Francis (1977), Frost & Lowry (1990), Frost, Lowry & Burns (1983), Frost, Lowry & Carroll (1993), Frost, Lowry & Nelson (1984, 1985), Gjertz & Wiig (1994), Gosselin (2005), Gosselin, Lesage & Hammill (2009), Gosselin, Lesage, Hammill & Bourdages (2002), Gosselin, Lesage & Robillard (2001), Gurevich (1980), Hammill (2001), Hammill et al. (2004), Harwood, Innes et al. (1996), Harwood, Norton et al. (2000, 2002), Hazard (1988), Heide-Jorgensen (1990, 1994, 2009), Heide-Jargensen & Acquarone (2002), Heide-Jargensen & Laidre (2006), Heide-Jorgensen & Rosing-Asvid (2002), Heide-Jorgensen & Teilmann (1994), Heide-Jorgensen & Wiig (2002), Heide-Jorgensen, Dietz, Laidre & Richard (2002), Heide-Jergensen, Dietz, Laidre, Richard et al. (2003), Heide-Jergensen, Hammeken et al. (2001), Heide-Jergensen, Jensen et al. (1994), Heide-Jorgensen, Laidre, Borchers et al. (2010), Heide-Jorgensen, Richard, Dietz et al. (2003), Heide-Jorgensen, Richard, Ramsay & Akeeagok (2002), Heide-Jorgensen, Richard & Rosing-Asvid (1998), Helbig et al. (1990), Hobbs, Laidre et al. (2005), Hobbs, Rugh et al. (1998), Hohn & Lockyer (1999), Huntington et al. (1999), Innes & Stewart (2002), Innes, Heide-Jorgensen et al. (2002), Innes, Muir et al. (2002), JCNB (2004, 2006), Jefferson et al. (2008a), Jonkel (1969), Kilabuk (1998), Kingsley (2000, 2002), Kingsley & Gauthier (2002), Kingsley et al. (2001), Kleinenberg & Yablokov (1960), Koski et al. (2002), Krahn et al. (1999), Laidre et al. (2000), Laurin (1982), Lawrence et al. (1990), Lebeuf et al. (2004), Lesage & Kingsley (1998), Lesage et al. (1999), Lewis, A.E. et al. (2009), Lewis, PN.B. & Pike (2004), Lockyer et al. (2007), Leno & Qynes (1961), Loseto et al. (2006), Lowry & Frost (1981, 1998), Lowry, Burns & Nelson (1987), Lowry, DeMaster & Frost (1996, 1999), Lowry, DeMaster, Frost & Perryman (1999), Luque etal. (2007), Lydersen et al. (2001), de March & Maiers (2001), de March & Postma (2003), de March, Maiers & Friesen (2002), de March, Stern & Innes (2004), Martin & Smith (1992, 1999), Martin, Hall & Richard (2001), Martin, Smith & Cox (1993, 1998), Martineau, Béland et al. (1987), Martineau, Lemberger et al. (2002), Michaud (1993), Mitchell & Reeves (1981), Moore & DeMaster (2000), Moore et al. (2000), Muir (1990), Muir, Ford, Rosenberg et al. (1996), Muir, Ford, Stewart et al. (1990), NAMMCO (2000, 2006), NMFS (2002, 2006), O'Corry-Crowe (2009), O'Corry-Crowe & Lowry (1997), O'Corry-Crowe, Dizon et al. (2002), O'Corry-Crowe, Suydam et al. (1997), Ognetov (1981, 1985, 1999), Orr et al. (1998), Palsbell et al. (2002), Recchia (1994), Reeves & Katona (1980), Reeves & Mitchell (1984, 1987 1989), Reeves et al. (2011), Remnant & Thomas (1992), Richard (1991b, 2005, 2010b), Richard & Pike (1993), Richard & Stewart (2008), Richard, Heide-Jergensen, Orr et al. (2001), Richard, Heide-Jergensen & St. Aubin (1998), Richard, Martin & Orr (1997 2001), Richard, Orr, Dietz & Dueck (1998), Richard, Orr & Postma (1990), Ridgway et al. (1984), Robeck et al. (2005), Rosenberg (2003), Schlundt et al. (2000), Seaman et al. (1982), Sergeant (1973), Sergeant & Brodie (1969a, 1969b, 1975), Shelden et al. (2003), Sjare & Smith (1986a, 1986b), Smith & Hammill (1986), Smith & Martin (1994), Smith & Sjare (1990), St. Aubin, DeGuise et al. (2001), St. Aubin, Smith & Geraci (1990), Stewart, B.E. & Stewart (1989), Stewart, D.B. et al. (1995), Stewart, R.E.A. (1994), Stewart, R.E.A. et al. (2006), Stirling (1980), Stirling & Cleator (1981), Suydam (2009), Suydam et al. (2001), SWG-JCNB (2005), Thomsen (1993), Tomilin (1957), Van Parijs et al. (2003a), Vergara (2011), Vladykov (1946), Wagemann et al. (1996), Welch et al. (1993).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Delphinapterus leucas

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2014 |

Delphinus leucas

| Pallas 1776 |