Catasticta cerberus Godman and Salvin, 1889

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1080/00222931003633227 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03F66F7D-AA13-BC08-FE02-FBB2FE71FC97 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Catasticta cerberus Godman and Salvin, 1889 |

| status |

|

Catasticta cerberus Godman and Salvin, 1889 View in CoL

This species ( Figure 22 View Figures 14–23 ) is endemic to Costa Rica and western Panama where it is restricted largely to Cordillera de Talamanca, generally in cloud forest at elevations above 2500 m ( DeVries 1987). It has also been recorded from Volcán Irazú in Cordillera Central ( DeVries 1987). The life history of C. cerberus has not previously been recorded. The following observations were made in Costa Rica, mainly at Cerro de la Muerte (3100 m a.s.l.) near Villa Mills and at Estación Biológica in Cordillera de Talamanca during 1998–2004. Additional observations were made at a site near Vara Blanca, Heredia Province, in Cordillera Central (2000 m a.s.l.), which represents a new locality and lower altitude limit for the species.

Immature stages

Egg

See Figures 109–111 View Figures 109–125 ; 1.0 mm high, 0.7 mm wide; deep bright yellow when laid, later changing to dull orange; barrel-shaped, with base flattened and much narrower in width than middle; chorion with numerous (approx. 28–30) longitudinal ribs, and a series of finer transverse lines between longitudinal ribs; apical rim with eight prominent paler nodules.

First-instar larva

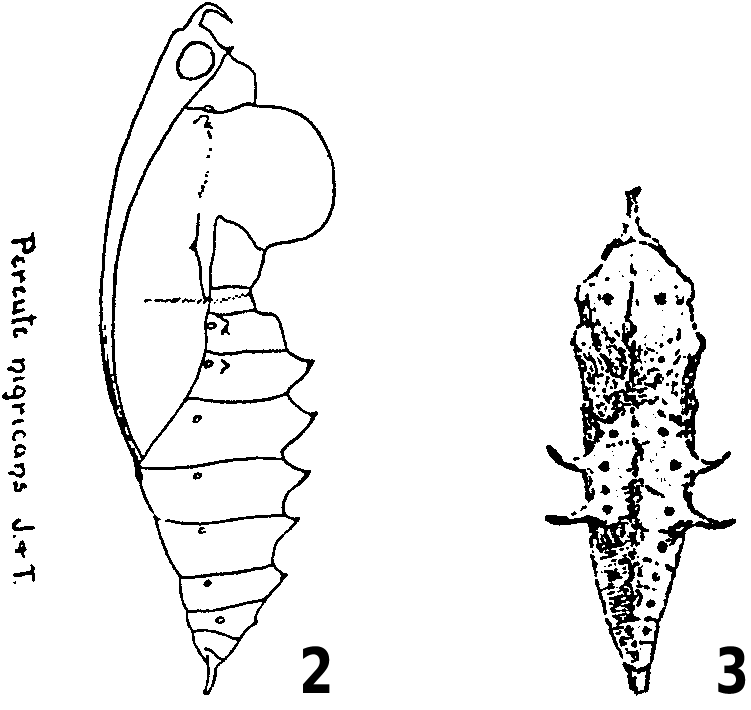

See Figures 112, 113 View Figures 109–125 ; 3.5 View Figures 2–3 mm long; head black, with a few primary colourless setae; body yellow, with numerous long, fine colourless primary setae; paired long black dorsal setae on meso- and metathorax and abdominal segments 1–8; prothorax with three subdorsal setae, two dorsolateral setae (one of which is black) and a lateral seta; mesothorax to abdominal segment 9 each with four setae (1 subdorsal, 1 dorsolateral, 2 lateral); abdominal segment 10 with reddish dorsal plate bearing setae.

Second-instar larva

See Figure 114 View Figures 109–125 ; 7 View Figures 4–13 mm long, head capsule 0.8 mm wide (n = 2); similar to first instar but body green, with primary setae white and arising from white protuberances; each segment with numerous short white secondary setae; prothorax with a broad reddish dorsal plate bearing six long white setae (in two groups, three on either side of middorsal line); abdominal segment 10 with a brown dorsal plate bearing several long white setae.

Third-instar larva

See Figure 115 View Figures 109–125 ; 10 View Figures 4–13 mm long, head capsule 1.2 mm wide (n = 6); similar to final instar.

Fourth-instar larva

See Figure 116 View Figures 109–125 ; 20 View Figures 14–23 mm long, head capsule 1.9 mm wide (n = 3); similar to final instar.

Fifth-instar larva

See Figures 117–121 View Figures 109–125 ; 28 View Figures 24–33 mm long, head capsule 3.0 mm wide (n = 4); head black, with numerous cream panicula from which arise white setae; body green, with numerous cream panicula from which arise white setae, and numerous very short brown secondary setae; prothorax with a dark brown rectangular-shaped dorsal plate bearing numerous setae; abdominal segment 10 with a dark brown dorsal plate bearing numerous setae.

Pupa

See Figures 122–125 View Figures 109–125 , 226, 227 View Figures 218–235 ; 18 View Figures 14–23 mm long, 5 mm wide (n = 19); predominantly reddish-brown, but with patches of black on thorax, scarlet on abdominal segment 9 and cremaster, and white in lateral areas of abdominal segments 4–9; head with a prominent orange anterior projection rounded apically, and a rounded subdorsal protuberance; prothorax with a pronounced longitudinal dorsal ridge; mesothorax with a pronounced cream longitudinal dorsal ridge (ending with black posteriorly), a double rounded scarlet lateral protuberance at base of fore wing, and a broad cream lateral ridge posterior to lateral protuberance; abdominal segment 2 with a rounded scarlet dorsolateral protuberance; abdominal segment 3 with a double rounded scarlet dorsolateral protuberance; abdominal segments 3–7 each with a middorsal ridge, more pronounced anteriorly; dorsal ridges scarlet anteriorly and white posteriorly.

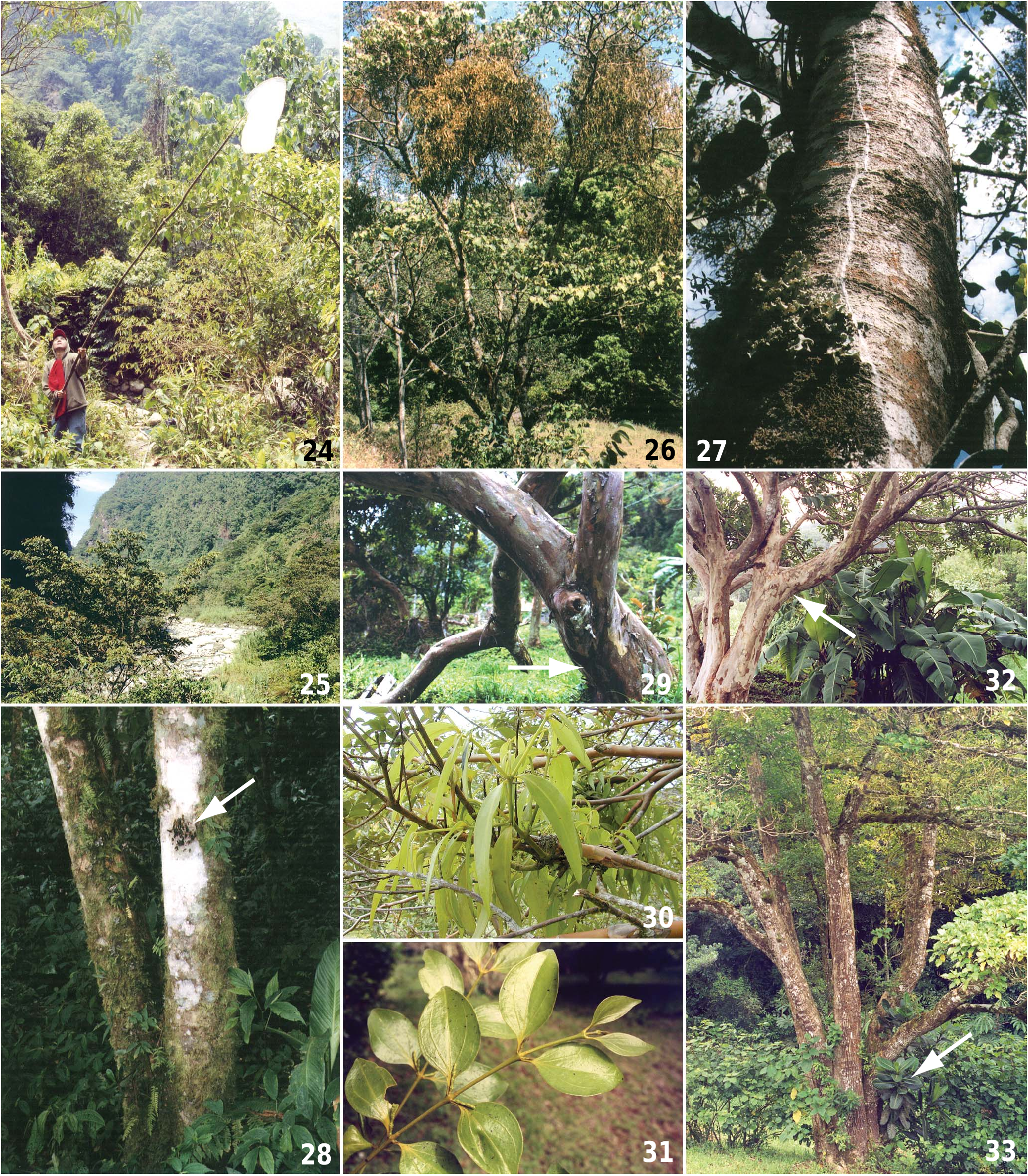

Larval food plants

In Costa Rica, many cohorts of the immature stages were found on the foliage of the mistletoe Dendrophthora costaricensis Urb. parasitizing a range of host trees ( Appendix 1), including Quercus costaricensis Liebm. (Fagaceae) , Pernettya prostrata (Cav.) DC. (Ericaceae) and Myrsine coriacea (Sw.) R. Br. ex Roem. and Schult. (Myrsinaceae) growing in montane cloud forest at elevations between 2000 m and 3100 m ( Figure 36 View Figures 34–44 ). In most cases, the preferred sites for breeding comprised the edge of the habitat (such as along tracks), rather than the shaded interior of the forest, where the larval food plants grew in the understorey 1–5 m from ground level in sheltered microhabitats, but where the canopy was slightly more open allowing filtered sunlight to penetrate.

Biology

Eggs were laid in small, loose clusters on the upper- or underside of leaves of the larval food plant, usually on the new terminal soft growth, with clutch sizes ranging from 7 to 17 eggs per cohort (x- = 10.3, n = 9 cohorts). The larvae of a given cohort emerged synchronously and, after hatching, the first-instar larvae proceeded to devour part of the chorion. The larvae fed gregariously in small groups on the underside of leaves, as well as on the flowers and, in the early instars, they closely resembled new developing flower buds. During wet, cool (<15ºC) weather, conditions typical of most afternoons, the larvae were noticed not to feed but remained at rest; in the late instars they typically rested on the underside of mature leaves where they were more protected and less exposed to rain. Pupae were not located on the larval food plant; however, on four occasions individual final-instar larvae were found either descending to the ground on silken threads, or were at rest or wandering on non-host substrates some distance from the food plant itself. These observations suggest that the larvae disperse from the food plant to pupate elsewhere. In captivity, all larvae pupated vertically with head oriented upwards, attached by the cremaster and a central silken girdle. The pupae were brightly coloured and resembled epiphylls, lichens, moss or fungi growing on the bark of the host tree. In captivity, adults took about 24 h to dry and fully harden their wings after emergence when reared at constant temperature (16–18°C).

Adults ( Figure 22 View Figures 14–23 ), unlike most species of Catasticta , flew fast with rapid wing beats similar to graphiine papilionids. Males were regularly observed to fly rapidly over the canopy and around the crowns of the tallest trees, 10–15 m high. Occasionally they settled at the tops of these trees, or sometimes lower down on Chusquea , where they basked in the sun for short periods, with wings opened at an angle of about 125º. They were not, however, observed to perch in the canopy and establish territories (cf. DeVries 1987). Females flew somewhat slower than that of the males. DeVries (1987) noted that adults are most active during the morning, a few hours after sunrise, and this agrees with our observations. At Cerro de la Muerte, adults were observed mainly during the morning between 09:30–12:30 h when conditions were sunny and temperatures reached their daily maximum (c. 15ºC). On most days, however, adults were active for only a few minutes and rarely more than 30 min owing to limited availability of sunlight and warmer temperatures – by mid- to late morning conditions were typically foggy and overcast owing to rising cloud, which later transpired to mist and then ultimately rain during the afternoon. Both sexes readily descended from the canopy to feed on flowers of plants growing in the ground or shrub layer, including Ageratina and Senecio (Asteraceae) , Pernettya prostrata (Ericaceae) , Gaiadendron punctatum (Ruiz and Pav.) G. Don (Loranthaceae) , Monoquitum (Melastomaceae), Fuchsia paniculata (Onagraceae) and Solanum (Solanaceae) .

The life cycle and number of generations completed annually is not fully understood, but adults appear to be very seasonal. DeVries (1987) remarked that the species is rare in collections, but adults are most common from February to April coinciding with the dry season. At Cerro de la Muerte, adults and eggs were recorded commonly in February and March, but adults were not observed on the wing again until August–October during the wet season when they were less abundant and more sporadic. When reared in captivity at constant temperature (16– 18°C), the larval and pupal stages took 36 d and 21–23 d, respectively, to complete development. However, these rearing conditions are well above the average temperature of 10.9ºC experienced at altitudes of 3100 m at Cerro de la Muerte, with nights falling below 0°C (minimum of –3ºC) during the dry season ( Kappelle 1996), so that development is undoubtedly substantially longer. Furthermore, conditions are frequently wet; the area receives a yearly annual rainfall of more than 2800 mm and heavy rains are common during the protracted wet season ( Kappelle 1996). Therefore, it is likely that larvae feed for only a few hours each day because of inclement weather in which conditions are frequently cold as well as wet. Indeed, two cohorts monitored in the field during July–September 2001 took more than 10 weeks (c. 75 d) to complete just the egg and first-instar larval stages. Hence, the life cycle from egg to adult probably takes many months to complete in the field and the adults are probably long-lived.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.