Dendrophidion clarkii Dunn

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.282529 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:2D771791-67EB-48A2-BB44-FD4B7F428723 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5628553 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03F4852C-5454-FFCE-FF1F-820DFE2DFB03 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Dendrophidion clarkii Dunn |

| status |

|

Figs. 4–11 View FIGURE 4 View FIGURE 5 View FIGURE 6 View FIGURE 7 View FIGURE 8 View FIGURE 9 View FIGURE 10 View FIGURE 11 , 14 View FIGURE 14 , 22 View FIGURE 22 B, 23A, 25, 28

Drymobius dendrophis (part). Boulenger 1894: 16 (specimen from “Quito”, Ecuador; BMNH 1892.2.26.8). Peracca 1896: 5 (“foreste del Río Cianati” [Darién, Panama]). Amaral “1929 ” [1930]: 154. Rendahl and Vestergren 1940: 3 (specimens from the western Cordillera of Colombia).

Dendrophidion dendrophis (part). Taylor 1951: 92

Dendrophidion clarkii . Dunn 1933: 78 (holotype: MCZ 34878; type locality: El Valle de Antón, Panama). Smith 1958b: 223. Lieb 1988: 166 –169 (synonym of D. nuchale ). Perez-Santos and Moreno 1988: 133. McCranie 2011: 105 –107 (part). Peters and Orejas-Miranda 1970: 80.

Dendrophidion nuchalis . Savage 1973a: 17 (part). Savage 1980: 17, 92 (part). Savage and Villa 1986: 17, 148, 169 (part). Lieb 1988 (part). Villa et al. 1988: 63 (part). Hayes et al. 1989: 49 (part). Ibáñez and Solís “1991 ”[1993]: 30. Pounds and Fogden 2000: 539 (part).

Dendrophidion nuchale . Scott et al. 1983: 372 (part). Almendáriz 1991: 216. Lieb 1991 (part). Pérez-Santos et al. 1993: 116 (part). Auth 1994: 15 (part). Pérez-Santos 1999: 99, 102 (part). Stafford 2003 (part). Goldberg (2003). Savage and Bolaños 2009: 14 (part). Bolaños et al. 2010 (part). Cadle 2012a (part).

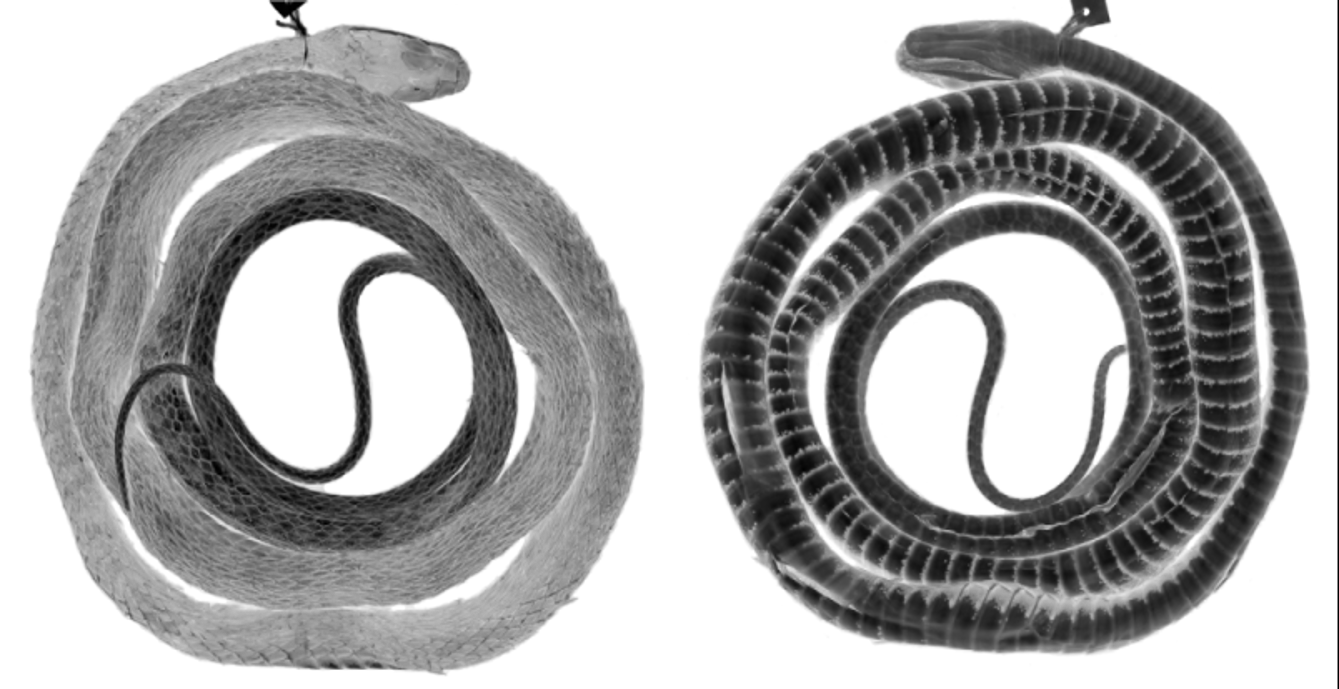

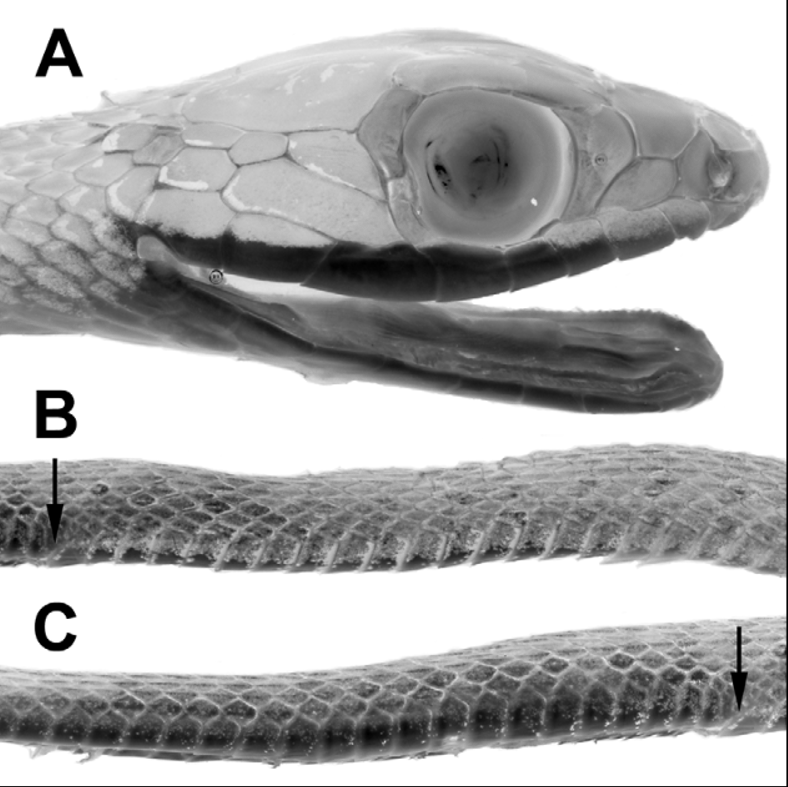

Holotype, MCZ 34878 ( Figs. 4–6 View FIGURE 4 View FIGURE 5 View FIGURE 6 ). Our scutellation and measurement data for the holotype ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 ) are essentially identical to those of Dunn (1933) given individual differences in methods of counting and measurement. The holotype is an adult male, 1078 mm total length, 406 mm tail length (672 mm SVL); 163 ventrals + 2 preventrals (Dunn: 165 ventrals), 141 subcaudals (Dunn: 142); dorsal scales in 17–17–15 rows, the posterior reduction at ventrals 92–93 by fusion of rows 3 + 4 (Dunn: loss of row 4). The anal plate is single, as reported by Dunn, but there is a partial division on its anterior edge. The dorsocaudal reduction from 8 to 6 occurs at subcaudal 42. Preoculars 1/1, postoculars 2/2; temporals 2 + 2 each side (upper right secondary divided); 9/9 supralabials with 2–3 contacting the loreal, 4–6 contacting the eye on each side; 10/10 infralabials. The last supralabial broadly contacts the lower primary temporal ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 A; supralabial/temporal pattern G of Cadle 2012b). Our maxillary tooth counts are 41/43 with the last four enlarged, which is the only significant departure from Dunn (1933), who reported 35 maxillary teeth.

Coloration. Dunn (1933:78) described the life colors of the holotype: “Head and anterior half green above; a black collar on temporals and behind parietals; upper lip white; posteriorly brown above; color of dorsum reaches onto ends of ventrals and on posterior half forms a narrow bar across anterior end of ventrals; belly white; tail lightbrown above, pinkish-white below.”

The coloration of the preserved holotype recorded in 2011 is as follows: Top of head and anterior body dark gray, grading to grayish brown and then more brown on posterior body. Tail pale brown or tan. Dark gray head cap down to upper edges of supralabials (covers slightly less than half of penultimate supralabial, slightly more than half of last supralabial). No evidence of the dark nuchal collar but the head cap is very dark and Dunn (1933) indicated a distinct black collar on the temporals and posterior to the parietal scales. Venter whitish with fairly uniform grayish lateral edges to ventral scales. Gular region and about the anterior 150 mm of head/body length immaculate other than this lateral pigment; posterior to this each ventral plate has a narrow transverse dark line on its anterior edge. Anteriorly, these lines are only at the lateral edges of the ventrals (broken midventrally), but on the posterior half or slightly more of the body the lines are continuous across the ventrals. The transverse lines rather abruptly peter out at the vent. Anterior subcaudals with a few small spots in more or less transverse rows along suture lines but most subcaudals are immaculate. Subcaudals with light lateral stippling but no distinct markings. No posteriolateral stripe or other distinct dorsal markings on the body or tail ( Figs. 5 View FIGURE 5 B, 5C). A few small pale flecks are visible on the posterior body in the positions where ocelli are usually present in the nuchale complex (dorsal rows 3 and 4) but these are very indistinct. No pale vertebral stripe.

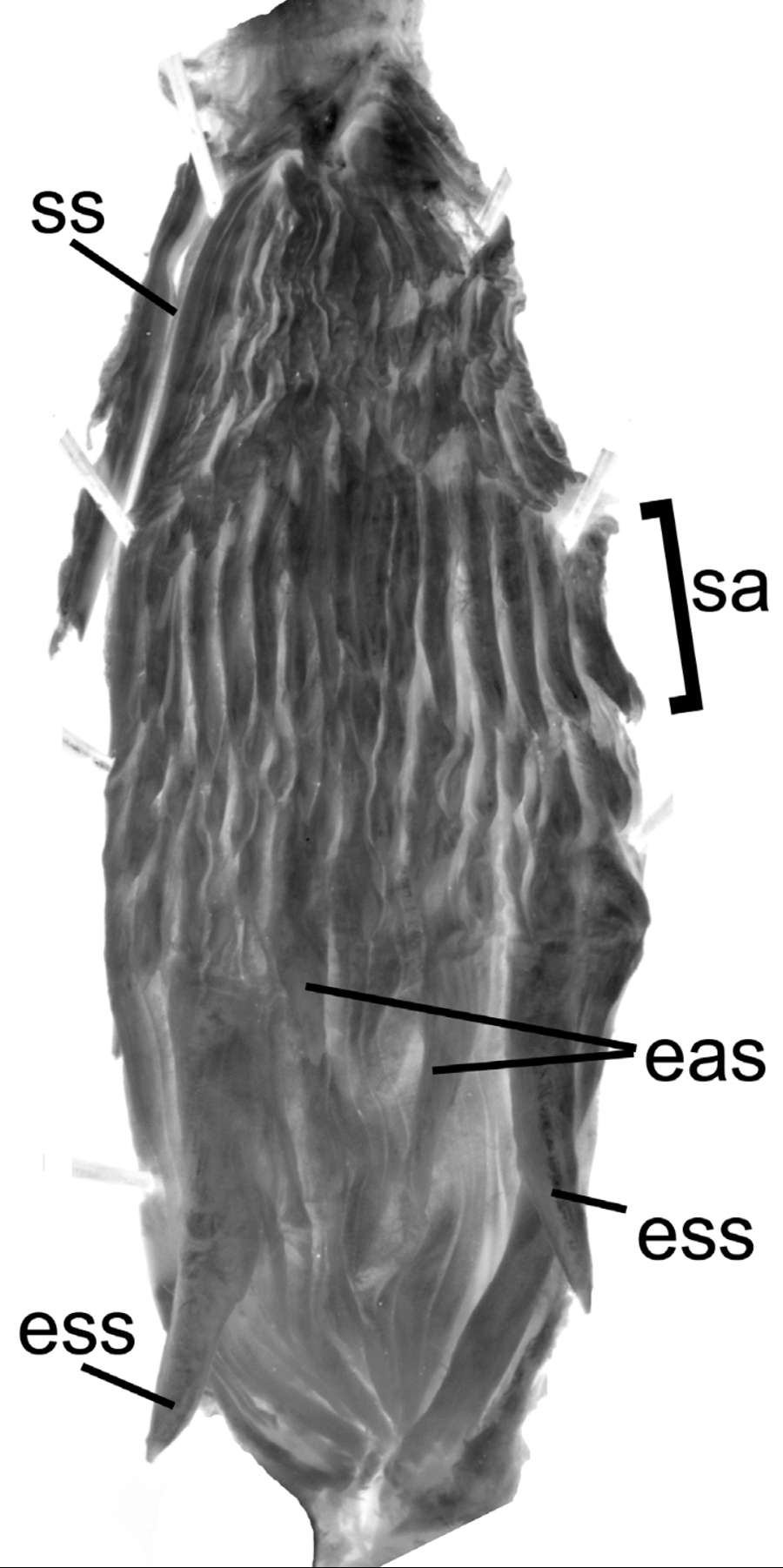

Hemipenis ( Fig. 6 View FIGURE 6 ). Retracted hemipenes of the holotype are asymmetrical in length. The left hemipenis extends to the middle or distal half of subcaudal 9; the right to the suture between subcaudals 7 and 8. Major retractors of both organs have a short proximal division and both have been severed. The asymmetry in lengths of the hemipenes may be related to the severing of the retractor muscles (e.g., if one was severed before, one after, preservation).

The left hemipenis has been slit on the lateral side mostly through the sulcus spermaticus except distally; it is apparently the hemipenis described by Dunn (1933). The sulcus spermaticus is simple, in the dorsolateral and lateral wall, and extends virtually to the tip of the organ. Most Dendrophidion sulci spermatici have flared tips (divergent lips); it was not possible to discern with certainty the condition of the D. clarkii type because of previous damage to the sulcus but the lips appeared somewhat divergent.

The proximal portion of the hemipenis is in longitudinal folds, smooth, and we detected no minute spines in this area. Distal to this is a broad area ornamented with enlarged spines, at the proximal edge of which are four spines much larger than any others (these are the “basal hooks” of Dunn [1933] and others); the lateral and the medial spines (with respect to the tail) are larger than the other two. Because the hemipenis was slit through the sulcus, the lateral and medial spines are the enlarged sulcate spines on the everted organ, i.e. those nearest the sulcus spermaticus; the two large spines between them are slightly more distally placed and correspond to the enlarged asulcate spines on the everted organ (see later hemipenial descriptions). Measurements of these spines, lateral to medial and measured along their distal surfaces (= superior surfaces in the everted organ) are 7.1 mm, 2.9 mm, 4 mm, 4.7 mm. Distal to these enormous spines are much smaller spines of uniform size in about three irregular rows on the sulcate and asulcate sides, two rows in between. The distalmost row of spines is a very regular (linear) row of 15 larger, relatively straight (hooked at the tip), robust spines; these are much larger than spines in the preceding rows but smaller than the proximal enormous spines. In everted organs described later the spines in this distal row form a morphologically distinct ring of large spines delimiting the distal border of the spine array; we refer to this row as the spinose annulus. The number of enlarged spines on the hemipenis is 15 (spinose annulus) + 33 smaller spines + 4 enormous proximal spines (= 52 total spines). A few other small spines are nestled among the spines of the annulus and adjacent to the sulcus.

Distal to the spines are two undulating flounces with embedded spinules. In the proximal flounce are a few small spines incorporated into the flounce wall, producing robust and somewhat protuberant spinules. There are moderately developed longitudinal connections between the flounces, especially on the lateral and asulcate sides (probably retain some calyxlike structure when everted). In addition, one (perhaps two) well developed calyces are adjacent to the sulcus spermaticus between the two flounces (because the organ was slit through the sulcus, a second calyx is possibly present but damaged); these two calyces have embedded spinules well developed in the longitudinal walls, whereas in most of the other longitudinal connections between the flounces the spinules are fewer in number and more poorly formed. Distal to the flounces are two or three rows of shallow calyces. These calyces extend to nearly to the tip of the organ on the asulcate side but stop short of the tip near the sulcus. Except for the distalmost calyces, these calyces also have embedded spinules. There are apical nude areas on each side of the distal portion of the sulcus.

Etymology. Dendrophidion clarkii is named after Herbert C. Clark, first director of the Gorgas Memorial Laboratory in Panama and overseer of the Panamanian Snake Census, which contributed immensely to knowledge of the snake fauna of Panama (see Dunn 1949, Myers 2003).

Diagnosis. Dendrophidion clarkii is characterized by (1) Dorsocaudal reduction from 8 to 6 occurring posterior to subcaudal 25 (range, 27–65); (2) anal plate usually divided (single in 8 of 45 specimens, partially divided in 1); (3) subcaudal counts> 135 in males and females; (4) head and anterior body of adults bright green, grading to brown posteriorly; (5) blackish or dark brown nuchal collar present in adults (less distinct or absent in juveniles); (6) posterior body brownish and having dark crossbands with embedded pale ocelli; tail brown to deep reddish, and either uniform (without crossbands) or with crossbands similar in overall pattern to posterior body; (7) ventral scutes in adults marked with narrow dark brown transverse lines across the anterior edge of each scute ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 ); (8) total number of enlarged spines on the hemipenis relatively few (<60); spines in the distal row uniform in size and numbering ≤ 15 (10–15).

No species of Dendrophidion except D. clarkii has a bright green head and anterior body combined with a black nuchal collar, so the adult coloration is diagnostic and distinguishes this species from all others. Dendrophidion clarkii differs from species of the D. percarinatum group in having a more distal dorsocaudal reduction (typically proximal to subcaudal 25 in the percarinatum group compared to> 25 in D. clarkii ). Single anal plates occur in the D. percarinatum group only in some individuals of D. paucicarinatum . Three species in the D. percarinatum group ( D. brunneum , D. bivittatum , and a new Ecuadorian species described by Cadle 2012b) can have a green head or anterior body but these lack a blackish nuchal collar and have different patterns on the posterior body ( Cadle 2010, 2012b). Dendrophidion boshelli has 15 dorsal scale rows at midbody (17 in D. clarkii ).

In addition to coloration, Dendrophidion clarkii differs from species of the D. dendrophis group as follows. The three species of the D. vinitor complex ( D. vinitor , D. apharocybe , D. crybelum ; Cadle 2012a) have distinct pale bands on the neck in adults and fewer subcaudals (<130) than D. clarkii (> 135). Dendrophidion dendrophis has a longer tail (> 70% of SVL in adults) and more subcaudals (≥ 150) than D. clarkii (<70% and usually <160, respectively). Dendrophidion atlantica lacks a nuchal collar and is brown on the anterior body.

Dendrophidion clarkii has previously been confused with the two other species of the nuchale complex, D. nuchale and D. rufiterminorum . Dendrophidion nuchale is allopatrically distributed from D. clarkii and both species have a blackish nuchal collar. Dendrophidion nuchale differs from D. clarkii in color pattern (anterior body never bright green in D. nuchale ) and usually has fewer ventrals than D. clarkii ( Table 1 View TABLE 1 ). Lieb (1988) mentioned that D. nuchale differed from D. clarkii in having dorsal scale row 1 unkeeled on the posterior body; while true of some individuals, others have keels on all rows, as in D. clarkii . The ranges of D. clarkii and D. rufiterminorum overlap in Costa Rica. The last species lacks a nuchal collar, has a reddish head and tail, and lacks extensive bright green on the anterior body. The tail of D. clarkii is deep red in some individuals but seemingly never in combination with a red head.

The dark nuchal collar and ventral markings are less distinct or absent in juveniles of D. nuchale and D. clarkii , and the red head and tail of D. rufiterminorum are less distinct or absent in juveniles. Thus, juveniles of these three species can be easily confused. The head of juvenile D. rufiterminorum is usually reddish brown and paler than the adjacent portions of the body (see Fig. 17 View FIGURE 17 ; the same individual is portrayed in Savage 2002: pl. 414 and Solórzano 2004: fig. 56); however, in photographs of D. rufiterminorum we have seen the tail is dull brown similar to the posterior body, lacking the reddish coloration and contrast seen in adults. The heads and tails of juvenile D. nuchale and D. clarkii are not differentiated in color (except greenish heads in D. clarkii ). The dorsocaudal reduction of D. rufiterminorum is distal to subcaudal 45 (<55 in D. nuchale and D. clarkii ; Table 1 View TABLE 1 ).

Description (27 males, 23 females). Table 1 View TABLE 1 summarizes size, body proportions, and meristic data for Dendrophidion clarkii throughout its geographic range. Largest specimen (USNM 150138 from Panama) a female 1550+ mm total length, 942 mm. Largest male (CAS 119604 from Colombia) 1521 mm total length, 909 mm SVL. Tail 34–40% of total length (52–68% of SVL) in males; 34–41% of total length (52–69% of SVL) in females. Dorsal scales usually in 17–17–15 scale rows, the posterior reduction usually by fusion of rows 2 + 3 (N = 26), 3 + 4 (N = 18), or loss of row 3 (N = 8) at the level of ventrals 83–115. Ventrals 158–175 (averaging 165) in males, 163–172 (averaging 167.2) in females; usually two preventrals anterior to ventrals (occasional specimens have one preventral). Anal plate divided in 35 out of 44 specimens (80%), single in 8 (17.8%), and partially divided in 1 specimen. Six of the specimens with a single anal plate are from Costa Rica and western Panama (one is from Ecuador, one probably from Colombia; the partially divided anal plate is in an Ecuadorian specimen). Subcaudals 139–161 (averaging 148.4) in males, 139–159 (averaging 148.9) in females. Dorsocaudal reduction at subcaudals 27–65 in males (mean 49.5), 28–63 in females (mean 51). Preoculars 1, postoculars 2 (rarely 3), primary temporals 2 (rarely 1), secondary temporals 2 (rarely 1), supralabials usually 9 with 4–6 bordering the eye (low frequency of other patterns; Table 1 View TABLE 1 ), infralabials usually 10 or 9 (low frequency of 8, 11, or 12). Maxillary teeth 36–52 (averaging 44.4), typically with 3 or 4 (occasionally 5) posterior teeth enlarged. Enlarged teeth are ungrooved, not offset, and there is no diastema.

Two apical pits present on dorsal scales. In most specimens all dorsal rows are keeled at mid- and posterior body (about 14% of specimens lack keels on row 1 at midbody and only 2 specimens lacked keels on row 1 posteriorly). Fifty-six percent of specimens lacked keels on dorsal row 1 on the neck, 32% had all neck rows keeled, and the remainder had 2 or 3 unkeeled rows on the neck. Fusions or divisions of temporal scales were infrequent (counting each side separately): upper primary or secondary divided (11% and 5%, respectively), lower primary or secondary divided (6%), other patterns (3%). Fifty-two percent of scorings for the supralabial/temporal pattern were G, 27% were P (the remaining were ambiguous or irregular). The only statistically significant differences between males and females were the number of ventral scales (greater in females) and the point at which the reduction in the dorsal scales occurred (more posterior in females) ( Table 1 View TABLE 1 ). In both cases the mean character differences were small.

Hemipenis unilobed, bulbous; overall morphology “robust morphotype” ( Cadle 2012b). Four enormous spines at the proximal edge of the spinose region (two on the sulcate side, two others toward the asulcate side). Spinose region followed distally by calyces/flounces in which the longitudinal walls are poorly developed. Apex with low rounded ridges, otherwise nude. Sulcus spermaticus simple, centrolineal, extending to the center of the apex, and having a slightly flared tip in everted organs.

Coloration in life. We are aware of only two previous color photographs of Dendrophidion clarkii in print media. Savage (2002: pl. 415) illustrated a specimen from Puntarenas province, Costa Rica (that specimen is now UCR 7421 and was published in black and white in Lieb [1991]). Ortega-Andrade et al. (2010: 148) illustrated a specimen from western Ecuador. Specimens from Panama and western Colombia are shown in Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 . Various websites we encountered feature photographs of this species, mainly from northwestern Ecuador where the species seems not uncommon.

Brief notes on the coloration in life of the holotype ( Dunn 1933) were quoted in the above description of the holotype. Dendrophidion clarkii as we conceive it is characterized, in adults, by a distinct black or dark brown nuchal collar, a bright green anterior dorsum in life (grading to greenish brown and then brown on the posterior body), dark crossbands with inset pale ocelli on the posterior dorsum, and narrow dark lines across the anterior edge of each ventral scute. The extent of the anterior green coloration in photographs we have seen varies from about one third to two thirds of the body length and the posterior region with dark crossbands is correspondingly longer or shorter (in a photograph of one specimen from western Panama it appeared that virtually the entire body, but not the tail, was bright green). There is usually a general darkening of the dorsal ground color posteriorly, and the posterior body can be nearly blackish. The tail in some photographs is deep red, similar to that in some specimens of D. rufiterminorum , but we have seen no D. clarkii with reddish pigment on the head. Juveniles are similar to adults in having a green head and anterior body ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 B) but there is seemingly variable expression of the dark nuchal collar in juveniles. For example, of two Panamanian specimens (225 and 256 mm SVL) for which color notes are quoted below, the smaller one had an indistinct nuchal collar but the larger one lacked a collar. Crossbars are usually evident on the anterior body in juveniles and they may be reddish brown to black.

Because further systematic partition of Dendrophidion clarkii may ultimately be warranted and because coloration characters seem especially significant within this complex, we provide the following color notes (paraphrased) for individual specimens, which may prove useful for future investigations.

LACM 148554 (male, 454 mm SVL; Las Cruces Biological Station, Puntarenas province, Costa Rica), from field notes of Carl S. Lieb for CRE 8675. Overall appearance is a bicolored snake (fore and aft) with a black nuchal collar. Top of head dark green with wide black collar extending from behind eyes to unite behind parietals. Labials cream. Iris dark brown, dorsal segment gold. Chin white. Anterior quarter of the dorsum uniform leaf green; second quarter dark reddish brown with very indistinct black crossbands; dorsal pattern then grading to dark brown with prominent black crossbands 1–1.5 dorsal rows wide. Pale ocelli present but indistinct within the dark bands. Interscale areas blue-green (turquoise). Posterior dorsum very dark walnut brown, with dark crossbands bearing more distinct yellowish ocelli. Where maximally expressed, ocelli are present in the vertebral region, dorsolaterally high on the body, and ventrolaterally at the juncture of the first dorsal row and ventral scutes (i.e., five ocelli in a transverse row). Blue-green interscale areas much reduced posteriorly, largely restricted to areas within the dorsolateral ocelli. Tail patterned similar to the posterior dorsum. Anterior ventrals yellowish, and with a narrow diffuse yellow band laterally. Lateral margins of the next series of ventrals (to about midbody) reddish brown laterally (with black specks at the medial margins of the reddish brown pigment), dirty white medially. Posterior to midbody the dark lateral pigment increases in density and expands medially; on the posterior body each ventral scute has a light salmon area where it overlaps with the next scute. Subcaudals with reddish lateral margins more vivid than the last ventrals, and lighter dirty yellowish medially.

The following color notes are from the field notes of Charles W. Myers for specimens from Panama, Colombia, and Ecuador.

AMNH 129758 ( Panama: Panamá). Juvenile female (225 mm SVL; Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 A). Head and neck green. Brown postocular stripe continues as less well-defined dark nape collar. Red-brown crossbands on green neck and more conspicuously (bolder) on rest of body, which is brown. Underside of head white, underside of neck grayish white, rest of venter very pale brown. Upper 1/3 of iris tan, lower 2/3 dark brown.

KU 110292 ( Panama: Darién). Juvenile female (256 mm SVL). Ground color of head and neck green to about level of ventral 28, thence turning orangish brown to midbody and brown thereafter. The black crossbars are broken by a fine vertebral line and lateral spots, all of which are pale tan except the line is lacking on the neck and the spots are pale greenish. The first few scale rows are strongly suffused with gray on the posterior half of body. Side of snout and first 3 supralabials pale gray. Other supralabials, last 4 infralabials, and tips of ventrals under neck yellow. Chin white, rest of venter pale, dirty gray. Upper quarter of iris tan, lower part deep brown. Tongue longer than head and uniformly black.

AMNH 109718 ( Colombia: Cauca). Adult female (894 mm SVL; Figs. 7 View FIGURE 7 B, 8C). Snout and top of head greenish gray, sharply demarcated from black band behind eye and across rear of head. Anterior 1/3 of body green, turning dark gray with black crossbands on posterior 2/3, and then dull red on tail. Concealed anterolateral scale bases bright yellow on anterior half of body (in the green and front part of the gray region). Supralabials white turning light yellow on posteriormost 3. Underhead also white, but venter otherwise golden yellow, with encroachment of gray pigment from sides. Iris brown. Tongue, including tips, black.

AMNH 109719 ( Colombia: Cauca). Adult male (818 mm SVL). Color like [AMNH 109718] except anterior body is brighter green and the body then turns red-brown for a short distance before changing to dark gray-brown of posterior body (and dark dull red on tail).

AMNH 109720 ( Colombia: Cauca). Adult female (890 mm SVL). Color like [AMNH 109718] except posterior body brown rather than gray.

AMNH 113019 ( Ecuador: Pichincha). Adult female (772 mm SVL). Above green anteriorly, becoming brown posteriorly. Belly yellow.

Color photos of a specimen from western Ecuador ( Ortega-Andrade et al. 2010: 148, “ Dendrophidion nuchale ”) show a pale gray head with contrasting black nape collar (followed by a few greenish gray scale rows), a bright green anterior body with a few blackish irregular narrow crossbands, and a posterior body with yellowish ocelli set within dark brownish black crossbands (ground color between crossbands dark grayish brown). Color transparencies of a small juvenile from western Ecuador (KU 164207, 313 mm SVL) show a dorsal ground color dull green on the anterior body gradually changing to greenish black on the posterior body and tail, a series of pale greenish white ocelli the entire body length, and a dark greenish gray/black nuchal collar contrasting with the (somewhat lighter) dark greenish head and neck (KU Digital Archive 010862 -63, Color Transparencies 5121-22).

Coloration of preserved specimens ( Figs. 8–11 View FIGURE 8 View FIGURE 9 View FIGURE 10 View FIGURE 11 ). In many relatively recently preserved examples, the green head and anterior body turns blue-gray or greenish gray. In those that have been preserved longer the anterior colors become a more or less uniform medium to dark gray with, at most, indistinct dark crossbands. In others (probably longer in preservative) the head and anterior body are almost black. Some exceptional older specimens maintain highly contrasting patterns ( Fig. 8 View FIGURE 8 B for example) and were probably preserved initially in alcohol. The remainder of the dorsum is brown to gray with narrow dark crossbands having embedded pale ocelli ( Figs. 8 View FIGURE 8 , 9 View FIGURE 9 A). The tail is medium brown to pale reddish brown with or without crossbands; it is often distinctly paler than the posterior body and in well preserved specimens can be reddish yellow or orange. The nuchal collar is frequently indistinct in adult preserved specimens because the dark nuchal collar tends to blend in with the dark gray or blackish (green in life) coloration of the anterior body ( Fig. 9 View FIGURE 9 B). The venter of adults ( Fig. 10 View FIGURE 10 ) has narrow transverse dark lines across the anterior edges of the ventral plates, at least on the posterior body. More extensive ventral pigment laterally and on the anterior edges of ventral scutes sometimes leaves a broad oval without pigment in the central part of the posterior scutes.

In juveniles with a complete set of crossbands visible, the total number of dark crossbands/transverse rows of ocelli is 52–71 (mean, 65.9; N = 12). Ocelli are generally present ventrolaterally on the lateral edges of the ventral scutes/dorsal row 1; laterally on rows 3 and 4 (sometimes involving row 2 as well), and the vertebral row (and adjacent paravertebral rows). The anterior body is greenish blue to slate blue, reflecting the green coloration in life ( Fig. 11 View FIGURE 11 ). The transverse lines on the venter are sometimes very distinct, occasionally reduced to heavy stipple along the anterior edges of the ventral scutes.

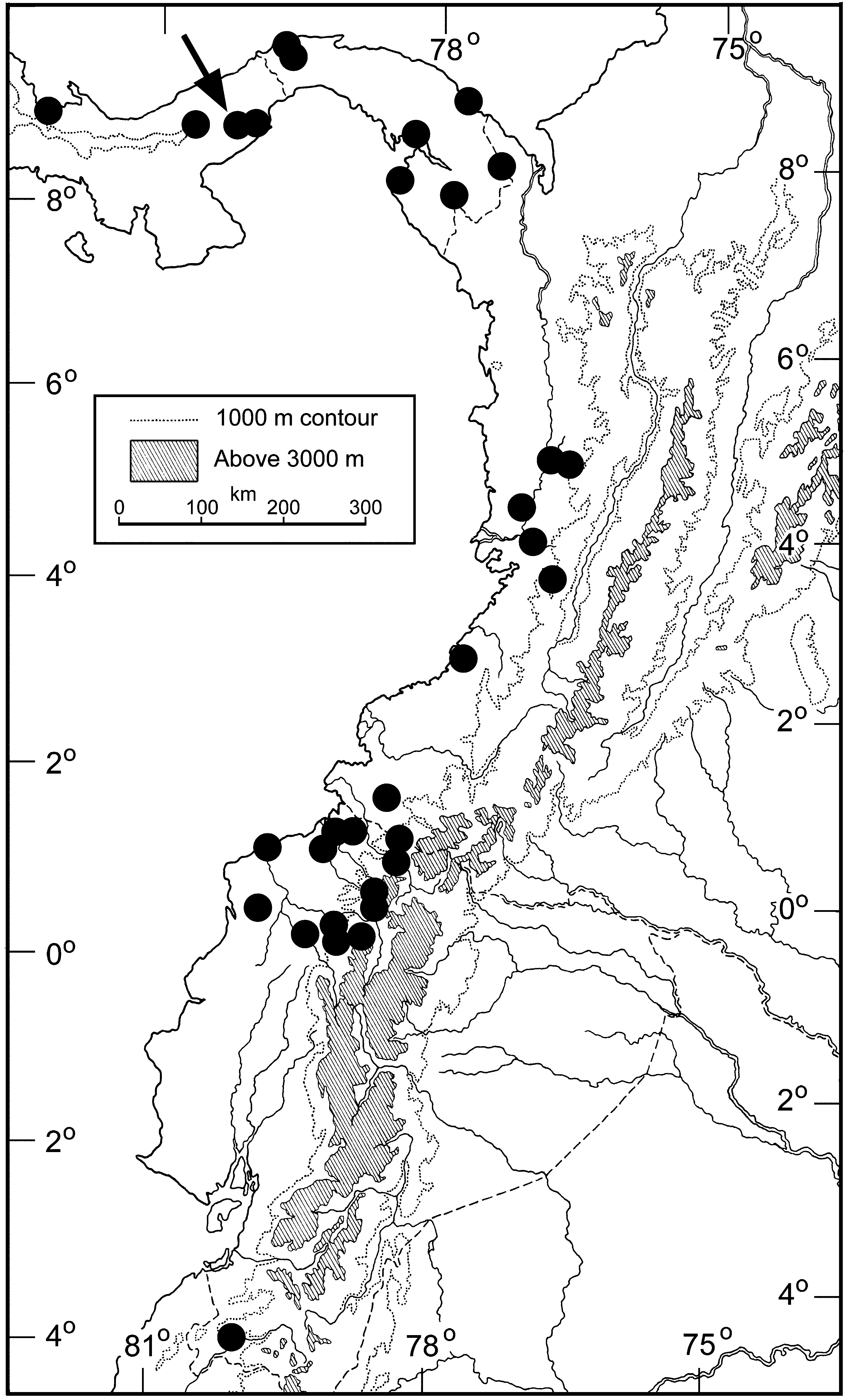

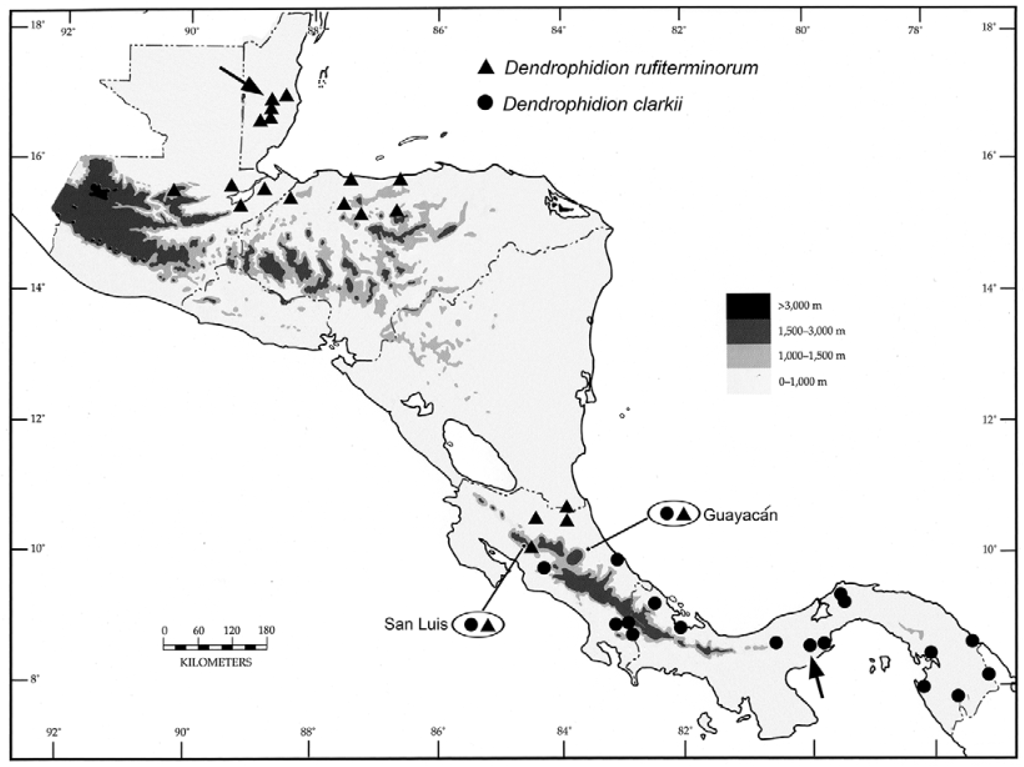

Distribution ( Figs. 12 View FIGURE 12 , 13 View FIGURE 13 , 20 View FIGURE 20 ). Dendrophidion clarkii as redefined herein (snakes with a distinct nuchal collar and vivid green anterior body in adults) is distributed from Costa Rica to western Ecuador. Locality records for D. clarkii in Costa Rica are shown in Fig. 12 View FIGURE 12 along with the southernmost records of D. rufiterminorum (discussed in its species account). The distribution of D. clarkii in eastern Panama and western South America is shown in Fig. 13 View FIGURE 13 ; see Fig. 20 View FIGURE 20 in the species account for D. rufiterminorum for a panoramic view of the Central American distribution of D. clarkii . Records for D. clarkii within its distribution are rather spotty except in northwestern Ecuador and it seems likely that the geographic range is in fact fragmented. We discuss the distribution in detail to highlight these potential disjunctions.

In Costa Rica Dendrophidion clarkii is known from two widely separated regions on the Pacific versant and from the Caribbean versant ( Fig. 12 View FIGURE 12 ). On the Pacific versant ten specimens document the species from the valley of the Río Térraba and one of its main tributaries (Río Coto Brus) in southern Puntarenas province. In northern Puntarenas a single specimen we refer to D. clarkii (LACM 148557) documents its presence in the upper San Luís valley. A sight record of a black-collared Dendrophidion with a green anterior body from the Puriscal area (western edge of the Meseta Central, 900–1000 m; personal communication from Alejandro Solórzano) provides another Pacific versant record of D. clarkii intermediate between the northern and southern Puntarenas localities. Although D. clarkii is known from as low as 75 m elevation in the Rio Térraba valley in southern Puntarenas (Appendix 1), it has not turned up in focused lowland herpetofaunal surveys on the Pacific versant at Carara National Park and the Osa Peninsula ( Laurencio & Malone 2009; McDiarmid & Savage 2005). We suspect that the distribution is now discontinuous on the Pacific versant of Costa Rica.

We are not aware of specimens of Dendrophidion clarkii from the Caribbean versant of Costa Rica ( Fig. 12 View FIGURE 12 ). Nonetheless, photographs of specimens from Limón province document its presence in the vicinity of Guayacán (photograph by Brian Kubicki), where it is sympatric with D. rufiterminorum (see Fig. 21 View FIGURE 21 B in the species account for the last species); and from the village of Río Blanco near Liverpool (photograph by Andres Vega, which was posted to the InBIO website as of June 2012, http://www.inbio.ac.cr/en/default.html). In addition, Gerardo Cháves, a herpetologist with extensive field experience in Costa Rica, informed us that he had observed a specimen conforming to our concept of D. clarkii (black nuchal collar, bright green anterior body) at Parque Nacional Barbilla (Limón/Cartago provinces near Guayacán; Fig. 12 View FIGURE 12 ).

In western Panama are three records of Dendrophidion clarkii from the Caribbean lowlands of Bocas del Toro province, followed by a gap until the next records in Coclé province (Omar Torrijos Herrera National Park and vicinity, and El Valle de Antón) and Cerro Campana on the Pacific versant of Panamá province ( Figs. 13 View FIGURE 13 , 20 View FIGURE 20 ). These last localities are indicative of a general pattern of “leakage” of elements of Caribbean slope fauna to the Pacific slope in west central Panama (see later distributional summary). Dendrophidion clarkii is known from the Atlantic and Pacific versants of Darién province before the range switches entirely to the Pacific versant of Colombia and Ecuador ( Fig. 13 View FIGURE 13 and Appendix 1).

In western Colombia the few localities are mainly from the lowlands and up to 915 m on the Andean slopes. Dendrophidion clarkii is not known with certainty from interandean valleys of northern Colombia (Río Cauca/ Magdalena system). MCZ R-22002, with the catalog entry “? Magdalena Valley”, is part of a small Colombian collection obtained by exchange in which several localities are entered with “?”; we discount the record unless confirmed by other collections. Rendahl and Vestergren (1940: 3, “ Drymobius dendrophis ”) reported four specimens collected by Kjell von Sneidern that possibly refer to D. clarkii (details these authors gave for one specimen are consistent with D. clarkii : 166 ventrals, entire anal, 152 subcaudals, and strongly keeled dorsal scales). If this identity is correct, then D. clarkii may occur on the eastern slope of the western Cordillera in Cauca province (specimens from El Tambo and Munchique; see Paynter 1997).

Dendrophidion clarkii has a relatively broad elevational range. Some records from near sea level (<100 m) occur throughout its distribution and most records are <1000 m. Upper elevational records are the following: 1800 m (southwestern Costa Rica), 1450 m (Darién, Panama), 1410 m (Carchí, Ecuador), 1340 m (Pichincha, Ecuador), and 1385 m (Loja, Ecuador).

Like some other parts of its range, the distribution of Dendrophidion clarkii in western Ecuador shows a peculiar disjunction ( Fig. 13 View FIGURE 13 ). After a relatively dense cluster of localities in northwestern Ecuador we are unaware of other specimens until the species is recorded again in extreme southwestern Ecuador (AMNH 22096) – approximately 475 km from the nearest record to the north. AMNH 22096 ( Fig. 14 View FIGURE 14 ) is a small juvenile male collected in August 1921, 269 mm SVL, single anal plate, 169 ventrals, 139 subcaudals, a dorsocaudal reduction at subcaudal 52, strongly keeled dorsal scales, a series of lateral ocelli on the body, and fine brown stippling across the anterior edge of the posterior ventrals (other pattern elements absent/obscure). These characters conform to our concept of D. clarkii and are unlike other Dendrophidion known from western Ecuador ( Cadle 2012b). Herpetofaunal surveys elsewhere in southwestern Ecuador have not recorded D. clarkii ( Yánez-Muñoz et al. 2009) .

Geographic patterns and systematic problems in Dendrophidion clarkii . Snakes to which we apply the name Dendrophidion clarkii are united by the distinctive black nuchal collar, a bright green head and anterior body, and dark transverse ventral lines in adults, as Dunn (1933) indicated for the holotype. Nonetheless, some patterns of variation and peculiar gaps in the distribution of these snakes give us pause and we would not be surprised if future studies result in further taxonomic partitioning of these populations. In particular, we note that the holotype lacks the distinctive (and usually prominent) dark crossbands or transverse rows of ocelli that are present on the posterior body and tail in most other specimens we have seen (e.g., compare Figs. 5 View FIGURE 5 B and 9A). Dunn (1933) mentioned no crossbands or ocelli in his brief color description of the specimen in life, although on the preserved specimen a few small lateral pale flecks are visible posteriorly under appropriate lighting conditions.

In fact, discounting excessively darkened specimens as a result of preservation artifact, we have seen only one other specimen lacking prominent dark crossbands or ocelli: USNM 347917, an adult (700 mm SVL) from Bocas del Toro province, Panama. The specimen is unfortunately a smashed road kill but it has a moderately distinct nuchal collar, a blue gray anterior dorsum, and no definitive dark crossbands or ocelli posteriorly. The posterior dorsum is mainly medium brown with occasional scales on row 3 and/or 4 with somewhat lighter centers (indistinct except under magnification). Ventrolateral ocelli are not evident. The ventrals on the posterior 1/2 to 2/3 of the body have dark lines across the anterior edges of the scutes. The top of the tail is medium brown, perhaps slightly lighter than the posterior body. The presence of a nuchal collar and a blue-gray anterior body are characteristic of Dendrophidion clarkii as we conceive it.

Given the pattern evident in the preserved holotype and in USNM 347917, it may be that adults on the western half of Panama lack the strongly banded patterns characteristic of specimens from southwestern Costa Rica (uplands of southern Puntarenas province), eastern Panama, and western Colombia and Ecuador ( Figs. 7–8 View FIGURE 7 View FIGURE 8 ); the other specimens we have seen from western Panama are all juveniles. We have seen photographs of two specimens from the vicinity of Parque Nacional Omar Torrijos Herrera in Coclé province, Panama (photographs by Roberto Brenes and Julie Ray). One specimen (possibly juvenile) is bright green anteriorly and brown on the posterior half or more of the body; it has dark crossbands/ocelli posteriorly but the posterior ground color and the crossbands are nearly the same shade and may be even less distinct when preserved, resulting in a more or less uniform posterior dorsum. The second specimen is bright green nearly the entire body length, seemingly lacks crossbands entirely, and has a deep red tail (this may be similar to the holotype in life, which is from a nearby locality). A specimen from eastern Costa Rica ( Fig. 22 View FIGURE 22 B in the account for D. rufiterminorum ) is green anteriorly and brown posteriorly but the crossbands and ground color are more similar, at least in part, because the snake is preparing to shed (blue eye). Additional adult specimens from western Panama and eastern Costa Rica would be helpful in interpreting the color variation apparent in preserved specimens. As indicated above (Description), six of the eight specimens with a single anal plate are from Costa Rica and western Panama. Whether these scale patterns and color differences signify unresolved systematic issues thus remains an open question.

Natural History. Most accounts in the literature of the natural history of Dendrophidion clarkii in Central America are a composite of D. clarkii and the new species described next (e.g., Savage 2002, Solórzano 2004); occasionally, D. nuchale is part of the mix as well (e.g., Stafford 2003). Fundamental aspects of the natural history of these species are similar. Two specimens we examined were terrestrially active midmorning or midday (KU 110292, AMNH 129758; field notes of Charles W. Myers). BMNH 1901.8.3.4 (western Ecuador), a female 878 mm SVL, contained 7 oviductal eggs approximately 25 mm long. USNM 150138 (eastern Panama) is a gravid female 942 mm SVL (eggs not counted) collected 1 March 1963. The incidence of broken/healed tails in our sample of Dendrophidion clarkii was 16%. Dendrophidion clarkii is seemingly an uncommon snake in Costa Rica and Panama given the relatively few specimens in collections despite focused herpetological field work in these countries.

| MCZ |

Museum of Comparative Zoology |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Dendrophidion clarkii Dunn

| Cadle, John E. & Savage, Jay M. 2012 |

Dendrophidion nuchale

| Savage 2009: 14 |

| Perez-Santos 1999: 99 |

| Auth 1994: 15 |

| Perez-Santos 1993: 116 |

| Almendariz 1991: 216 |

| Scott 1983: 372 |

Dendrophidion nuchalis

| Pounds 2000: 539 |

| Hayes 1989: 49 |

| Villa 1988: 63 |

| Savage 1986: 17 |

| Savage 1980: 17 |

| Savage 1973: 17 |

Dendrophidion dendrophis

| Taylor 1951: 92 |

Dendrophidion clarkii

| McCranie 2011: 105 |

| Lieb 1988: 166 |

| Perez-Santos 1988: 133 |

| Peters 1970: 80 |

| Smith 1958: 223 |

| Dunn 1933: 78 |

Drymobius dendrophis

| Rendahl 1940: 3 |

| Peracca 1896: 5 |

| Boulenger 1894: 16 |