Melophorus anderseni, Agosti, 1997

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.7677016 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7677018 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03F187EC-6206-FF82-FE91-FF04FC195917 |

|

treatment provided by |

Donat |

|

scientific name |

Melophorus anderseni |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Melophorus anderseni View in CoL , new species

Holotype -worker: Australia, NT, Darwin , CSIRO, backyard of Division of Wildlife and Terrestrial Ecology. 3.ii.1991, D. Agosti. Holotype deposited at ANIC. Figures 1 View Figs -5 .

Paratypes. 8 workers and 1 female; Australia, NT, Darwin , CSIRO, backyard of Division of Wildlife and Terrestrial Ecology. 3.ii.1991, D. Agosti. Paratypes deposited at AMNH, ANIC, BMNH, CSIRO-TERC, MCZ, MHNG .

Holotype worker: TL 1.84, HL 1.06, HW 1.00, SL 1.34, EL 0.26, CI 94, El 26, SI 134.

Paratype workers (N = 7): TL 1.82-1.99, HL 1.08-1.14, HW 1.0-1.10, SL 1.24- 1.48, EL 0.24-0.26, CI 91-96, EL 23-26, SI 127-148; female (N = 1) TL 2.92, HL 1.68, HW 2.08, SL 1.24, EL 0.38, CI 124, El 18, SI.60

Description: Worker:

—Clypeus pointed and keeled, slightly projecting anteriorly

—Maxillary and labial palps extremely thin, not longer than half the head length

—long psammochaeta: J-shaped hairs on the clypeus, gula and maxillary stipes

—Long scape

—Mesosoma elongate with pronotum in cross-section dorsally rounded, and propodeum smoothly rounded

—Petiole nodiforme

—Short erect hairs on mesonotum, propodeum, petiole, gaster and legs.

—Body color reddish orange, with the gaster at most slightly darker

—Body not shining, and without a distinct sculpture

Female:

—same as worker, but with a complete set of wing sclerites, and the following differences

—larger than the worker

—distinctly much wider head than the worker.

Material examined: Holotype and paratypes.

Comment: The above combination of characters is unique within the genus. Other ants related to Iridomyrmex species are usually characterized by a stout body shape, short appendages and an excessive number of long hairs, or short and thick hairs, e.g., fidvihirtus ( Clark, 1941). No large workers were observed, but, as it was a unique nest in perfect position to be observed further, it was not dug out completely. In many respects, this species with the nodiforme petiole, the smooth shining surface, and the few hairs resembles more M. bagoti .

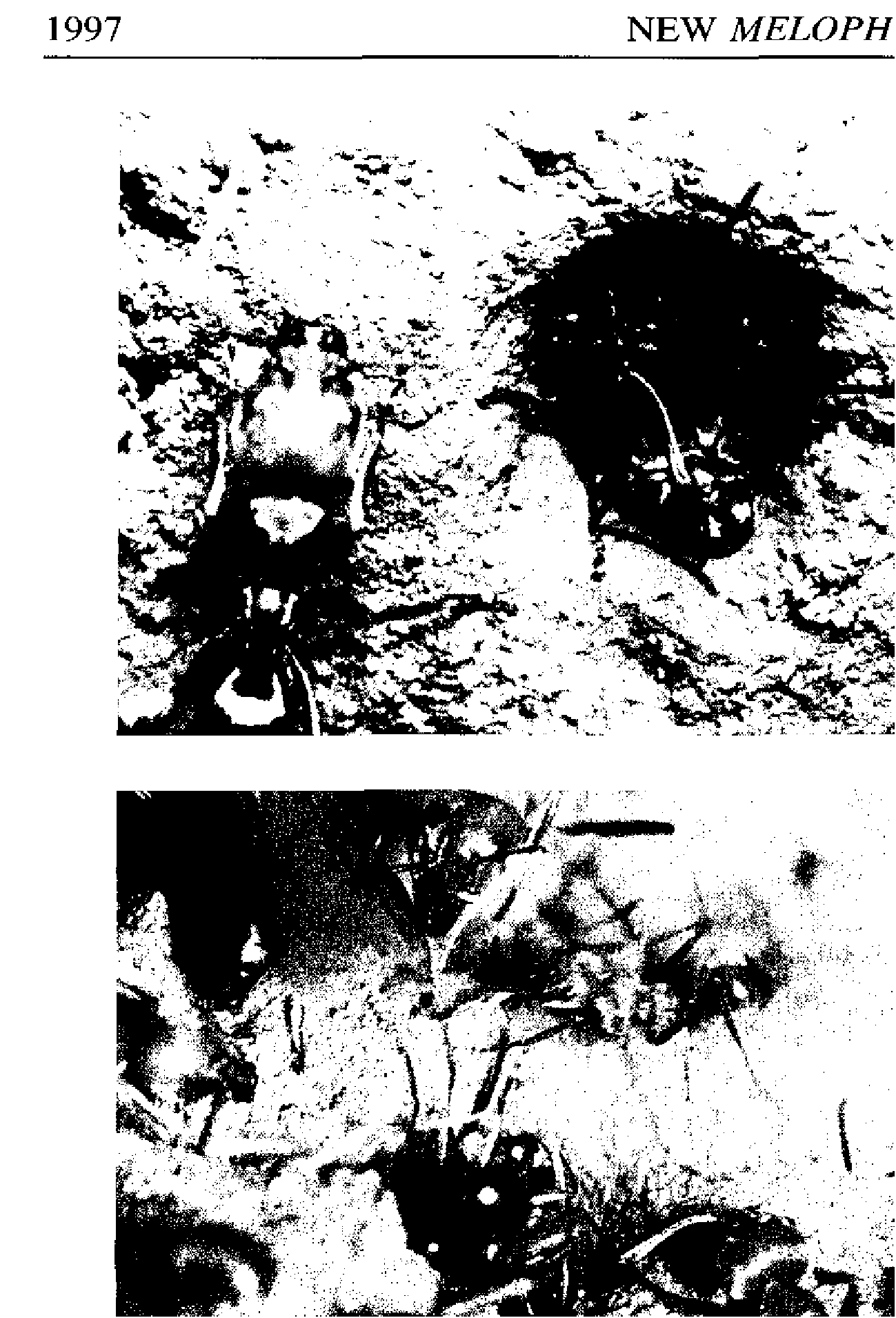

Biology: M. anderseni was discovered whilst collecting a sample of Iridomyrmex sanguineus on the large pebble nest in the garden of the CSIRO Division of Terrestrial Ecology in Darwin, which just had the males leaving in the late morning. This very dominant species has little nest entrances, which three workers at a time seal off when threatened ( Fig. 1 View Figs ). The seal is so tight that it is impossible to remove this plug, without tearing off the antennae of the workers. At the very time, it did not take the guards long to step aside, as the nest was just swarming and many males were leaving and entering the nest. The meat ant, I. sanguineus , is a very distinct species. It is easily recognized by the large soil material scattered around the nest entrances, their steady pace, the bright red head and mesosoma, the relatively wide, heart-shaped head with the rather narrowly set eyes, and if there are any doubts left, there stinking smell when squeezed between the fingers.

It was then very remarkable to discover, that there was a second species of ants intermingled with the workers, which even entered and left the nest entrances— albeit at a higher speed—with the Iridomyrmex workers ( Fig. 2 View Figs ). Some of the anderseni were even carrying larvae out of the sanguineus nest. Following these workers, they disappeared into entrances at the outskirts of the sanguineus nest, with much narrower entrances, so that only these workers and not the sanguineus could enter. Obviously, the sanguineus workers did not care at all about the robbery. However, two more observations point out that this is a more complex interaction. In two cases, workers of anderseni were seen staying above the sanguineus , seemingly rubbing their bodies against one of the sanguineus ( Fig. 3 View Figs ), which during this period did not move at all, but behaved similarly to an ant encountering a larger, nonconspecific ant. One way to react in such a situation is cowering on the ground, with legs and antennae as drawn up as possible, which is in this case with the smaller ant dominating over the larger. After about a minute, anderseni left without any further interactions with the meat ant. It seems as if the anderseni workers acquires the very pungent smell of the sanguineus , making her chemically invisible.

Cuticular hydrocarbons are assumed to be used as recognition cues (Nowbahari et al., 1990). The breakdown of nest mate recognition has been documented within species ( Jeral et al., 1997), between ant species (e.g., Hölldobler, 1973; Lenoir et al., 1997), in many cases of the lycaenid-ant relationship, or many myrmecophiles ( Hölldobler and Wilson, 1990). At least three types of breakdowns are known. In the thief ant Ectatomma ruidum a decreased amount of cuticular compounds might play the facilitator role ( Jeral et al., 1997). Other ants and guests acquire the host odor either passively or actively by licking the host (known from many myrmecophilous beetles or ants of the genus Formicoxenus ). Finally, the compounds are actively biosynthesized by the guests ( Lenoir et al., 1997, Lorenzi et al., 1996). M. anderseni undoubtedly must belong to the second category.

Among Australian ants, robbing of ant nests by other species seems to be rather widespread. More nest entrances are locked up after periods of activities in Australia than in other regions of the world. Cerapachys species can be seen quiet often carrying away brood from other ant nests, during the hottest ours of the day, or early in the morning ( Clark, 1941; Agosti, unpubl.). Whereas raids of ant nests by Cerapachys include a number of workers, often accompanied by intense fights between the hosts, the two known Melophorus species, fulvihirtus and anderseni , operate singly, and are not recognized by their hosts ( Clark, 1941). In some cases, when a meat ant seemed to notice an anderseni worker, the latter stopped moving for a moment, and almost played dead.

The other significant observation was that the sanguineus workers started to cover the nest entrance of the anderseni with small pebbles, until a distinct heap was formed, similar to the nest plugging described in North American desert ants (Möglich and Alpert, 1979; Gordon, 1988).

Robbing of meat ant larvae was described by Clark, 1941. M. fulvihirtus , a morphologically very distinct species, also lives at the outskirts of meat ant nests.

| CSIRO |

Australia, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation |

| ANIC |

Australia, Australian Capital Territory, Canberra City, CSIRO, Australian National Insect Collection |

| AMNH |

USA, New York, New York, American Museum of Natural History |

| BMNH |

United Kingdom, London, The Natural History Museum [formerly British Museum (Natural History)] |

| MCZ |

USA, Massachusetts, Cambridge, Harvard University, Museum of Comparative Zoology |

| MHNG |

Switzerland, Geneva, Museum d'Histoire Naturelle |

| CSIRO |

Australian National Fish Collection |

| ANIC |

Australian National Insect Collection |

| AMNH |

American Museum of Natural History |

| MCZ |

Museum of Comparative Zoology |

| MHNG |

Museum d'Histoire Naturelle |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |