Leopardus wiedii (Schinz, 1821)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1206/00030090-417.1.1 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03E587EC-FF85-FF80-7731-FA2A8184FBEA |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Leopardus wiedii (Schinz, 1821) |

| status |

|

Leopardus wiedii (Schinz, 1821) View in CoL

Figure 14C View FIG

VOUCHER MATERIAL (TOTAL = 1): Boca Río Yaquerana (FMNH 88889).

OTHER INTERFLUVIAL RECORDS: Nuevo San Juan (this report), Río Yavarí-Mirím (Salovaara et al., 2003), San Pedro (Valqui, 1999).

IDENTIFICATION: The only available margay specimen from the Yavarí-Ucayali interfluve consists of the skin and skull of a young adult male ( FMNH 88889 About FMNH ). Although margays are much smaller than ocelots on average, large specimens of margays are sometimes confused with small specimens of ocelots ; fortunately, these species are readily distinguished by tail length and cranial proportions (Pocock, 1941). Based on collectors’ measurements ( table 12 View TABLE 12 ), the ratio LT/ HBL × 100 equals 65% for our margay voucher versus 44%–48% for three adult ocelot vouchers. 9 Additionally, the tanned skin of FMNH 88889 can be folded to show that the tail is substantially longer than the hind leg (a useful field character mentioned by Emmons, 1997), whereas the tail is substantially shorter than the hind leg on the ocelot skins that we examined.

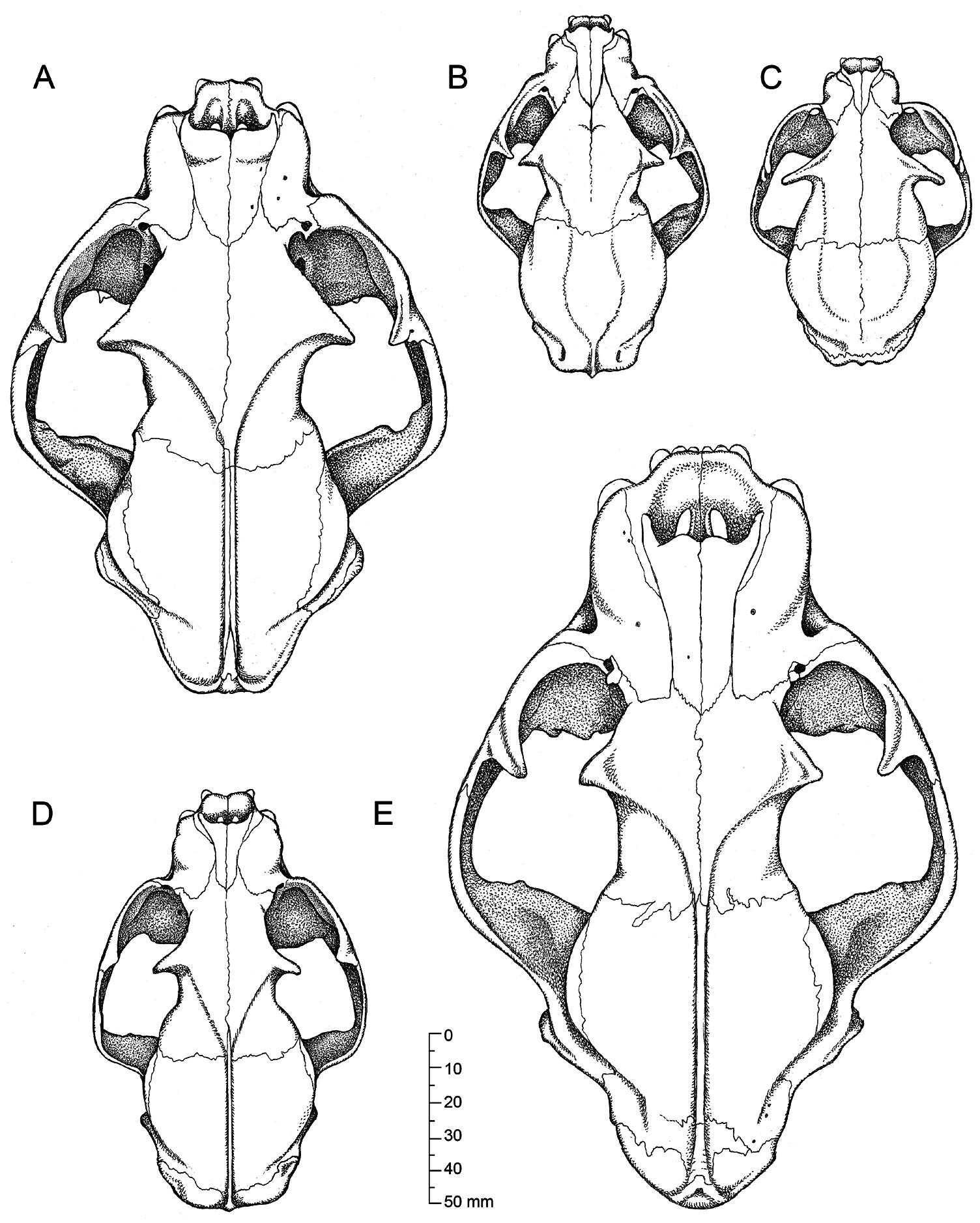

The postorbital constriction is much wider than the interorbital constriction in Leopardus wiedii by contrast with L. pardalis , whose postorbital and interorbital constrictions are more nearly equal (Pocock, 1941). For FMNH 88889, the postorbital constriction is approximately twice as wide as the interorbital constriction (LPB/LIB × 100 = 204%), whereas this ratio ranges from 118% to 137% among our four adult ocelots. In dorsal view, margay skulls have larger orbital fossae than temporal fossae, whereas ocelots have larger temporal than orbital fossae. Lastly, margay skulls usually lack a sagittal crest, whereas most fully adult ocelots have well-developed sagittal crests. These cranial differences are visually conspicuous (fig. 14).

The last comprehensive revision of Leopardus wiedii was Pocock’s (1941), which restricted the nominotypical form to southeastern Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay; in his classification, western Amazonian margays were referred to L. w. pirrensis (Goldman, 1920), with type locality in eastern Panama. However , amazonicus Cabrera, 1917, based on a specimen from Tabatinga, Brazil, would appear to be the appropriate

name if western Amazonian populations were judged to be taxonomically distinct from other margays (Oliveira, 1998b).

ETHNOBIOLOGY: The margay is called tëstuk mawekid, which literally means “one that lays under epiphytes” owing to its habit of lying on tree limbs under the cover of large-leaved arboreal plants. The margay is sometimes called bëdimpi (ocelot) by observers unfamiliar with the species, but more knowledgeable Matses hunters say that this usage is incorrect.

The margay is of no economic importance to the Matses. Only rarely does one approach the outskirts of a Matses village to stalk chickens in the daytime. Unlike ocelots, margays do not raid chicken coops at night.

Matses with young children avoid having any contact with or even looking at margays, lest the margay’s spirit make their children ill (see the ethnobiology entry for the puma for details on symptoms and treatment of contagion by felids).

MATSES NATURAL HISTORY: The margay is small and spotted. It has a long tail.

The margay is found in any habitat, including floodplain and upland forest. It is more frequently found in primary forest than in secondary forest (e.g., sites of abandoned swiddens). It is more rarely encountered than the ocelot .

The margay spends much of its time lying up in the trees, on tree branches or on upward-spiraling lianas. It walks up inclined trees and lies on the inclined trunk waiting for prey to pass by underneath. As it lies on a branch, tree, or liana, it hides under epiphytes or thick vegetation. It also lies in the open on branches or inclined tree trunks to rest after eating and to sleep. It also hunts by searching for prey on the ground, but it does not lie down on the ground.

The margay is solitary. It gives birth to two kittens in a hollow log on the ground or in a burrow, not up in the trees.

A margay may pounce on a tinamou that passes under the tree where the cat is waiting. Margays walking on the ground also kill tinamous, pouncing on them from far away. At night margays find tinamous sleeping on low perches. Margays pluck the feathers from tinamous before eating them. Margays kill other animals in the same ways (from ambush and by active diurnal and nocturnal hunting).

The margay growls when it is taking prey.

The margay eats pacas, agoutis, acouchies, spiny rats, other rats and mice, squirrels, common opossums, four-eyed opossums, and mouse opossums. It also eats white-throated tinamous ( Tinamus guttatus ), great tinamous ( T. major ), smaller tinamous (Crypterellus spp.), other terrestrial birds, and small arboreal birds. It also eats lizards, tree frogs, and jungle frogs (Leptodactylu s spp.).

REMARKS: Matses observations broadly agree with the scattered scientific literature on this small cat (reviewed by Oliveira, 1998b), notably with respect to its arboreal habits, denning behavior, and the wide range of prey taken. Matses accounts of arboreal ambushing versus active terrestrial searching, however, suggest a characteristic foraging strategy that is not described as such in the literature, nor does the literature describe several other details of margay predatory and feeding behaviors (e.g., feather-plucking) mentioned by our informants.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.