Johngarthia lagostoma (H. Milne Edwards, 1837)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5146.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:52C3E5E3-80B6-49DB-BC9C-194560D491F7 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7626418 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03E3878A-A82D-FFFF-04F4-8D68FD47F88D |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Johngarthia lagostoma (H. Milne Edwards, 1837) |

| status |

|

Johngarthia lagostoma (H. Milne Edwards, 1837) View in CoL View at ENA

( Figs. 46A–I View FIGURE 46 , 47A–G View FIGURE 47 , 48A–F View FIGURE 48 )

Gecarcinus lagostoma H. Milne Edwards, 1837: 27 View in CoL [ Type locality: Ascension Island].

Trindade and Martin Vaz specimens. 1 male ( MZUSP 9583 View Materials ), Brazil , off Espírito Santo , Trindade Island, Enseada dos Portugueses, M. Tavares and F. W. Kurtz coll., 13.xii.1986 . 1 male ( MZUSP 21430 View Materials ), ibidem, Praia das Cabritas , M. Tavares and F. W. Kurtz coll., 13.xii.1986 . 2 parental females each with hatched first stage zoeae ( MZUSP 40221 View Materials and 40223), ibidem, 20°30’24’’S, 29°18’57”W, J.B. Mendonça coll., 10.xi.2014 GoogleMaps . 1 juvenile male, cl 9.1 mm, cw 10.6 mm ( MZUSP 40322 View Materials ), Praia da Tartaruga , 20°31’03.8’’S, 29°18’08.4”W, J.B. Mendonça coll., 10.vi.2012 GoogleMaps , at night. 1 female, cl 22 mm, cw 26 mm; 1 male, cl 30 mm, cw 36 mm; 1 male cl 32 mm, 38 mm ( MZUSP 40321 View Materials ), ibidem, Enseada dos Portugueses, 20°30’27.8’’S, 29°18’50.2”W, J.B. Mendonça coll., 15.vii.2013 GoogleMaps . 1 juvenile female, cl 20 mm, cw 23 mm; 1 juvenile male, cl 22 mm, cw 26 mm; 1 juvenile male, 1 juvenile female both cl 23 mm, cw 27 mm; 1 juvenile male cl 28 mm, cw 33 mm ( MZUSP 40352 View Materials ), ibidem, 12.vii.2015 . 1 juvenile female cl 14 mm, cw 16 mm ( MZUSP 40226 View Materials ), ibidem, J.B. Mendonça coll., 14.ii.2018 . 2 males, 4 females ( MZUSP 22792 View Materials ), Trindade Island , Pico do Desejado, TAAF MD55/ Brésil Expedition, M. Tavares coll., 22.v.1987 , altitude around 600 m . 1 male ( MZUSP 17279 View Materials ), Martin Vaz Archipelago, 10.x.1988.

Size of largest male: cl 66 mm, cw 79 mm; largest female: cl 67 mm, cw 76 mm.

Comparative material examined. Brazil: 1 male ( MZUSP 36387 View Materials ) , 1 female ( MZUSP 3685 View Materials ), Rocas Atoll, ii.1972 . 1 female ( MZUSP 30021 View Materials ), Fernando de Noronha, Baía dos Porcos, Pedreira do Sueste , 14–16.x.2006 .

Distribution. Insular. Rocas Atoll, Fernando de Noronha Archipelago, Ascension Island, Trindade and Martin Vaz Archipelago ( Moreira 1901; 1920; Lobo 1919; Manning & Chace 1990).

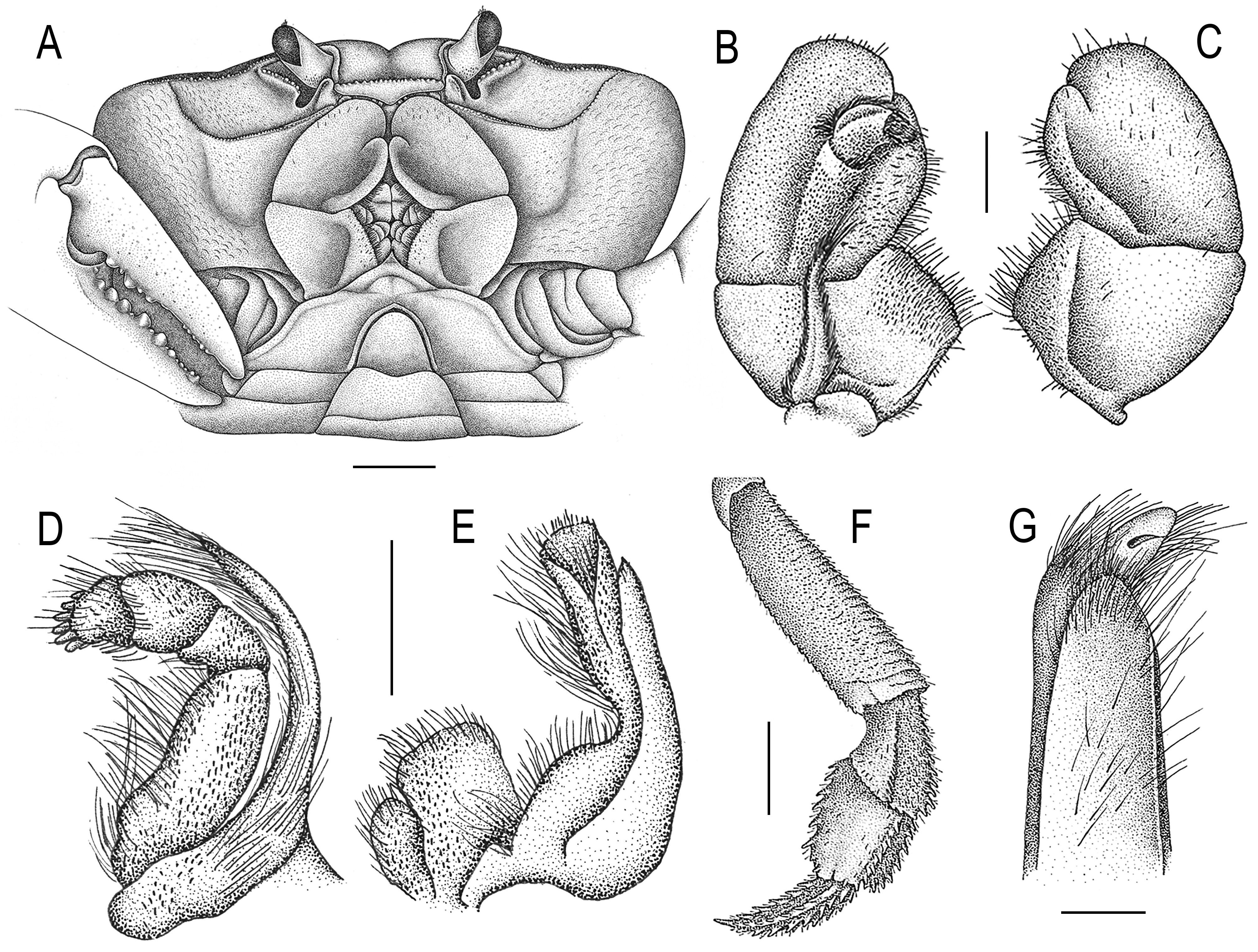

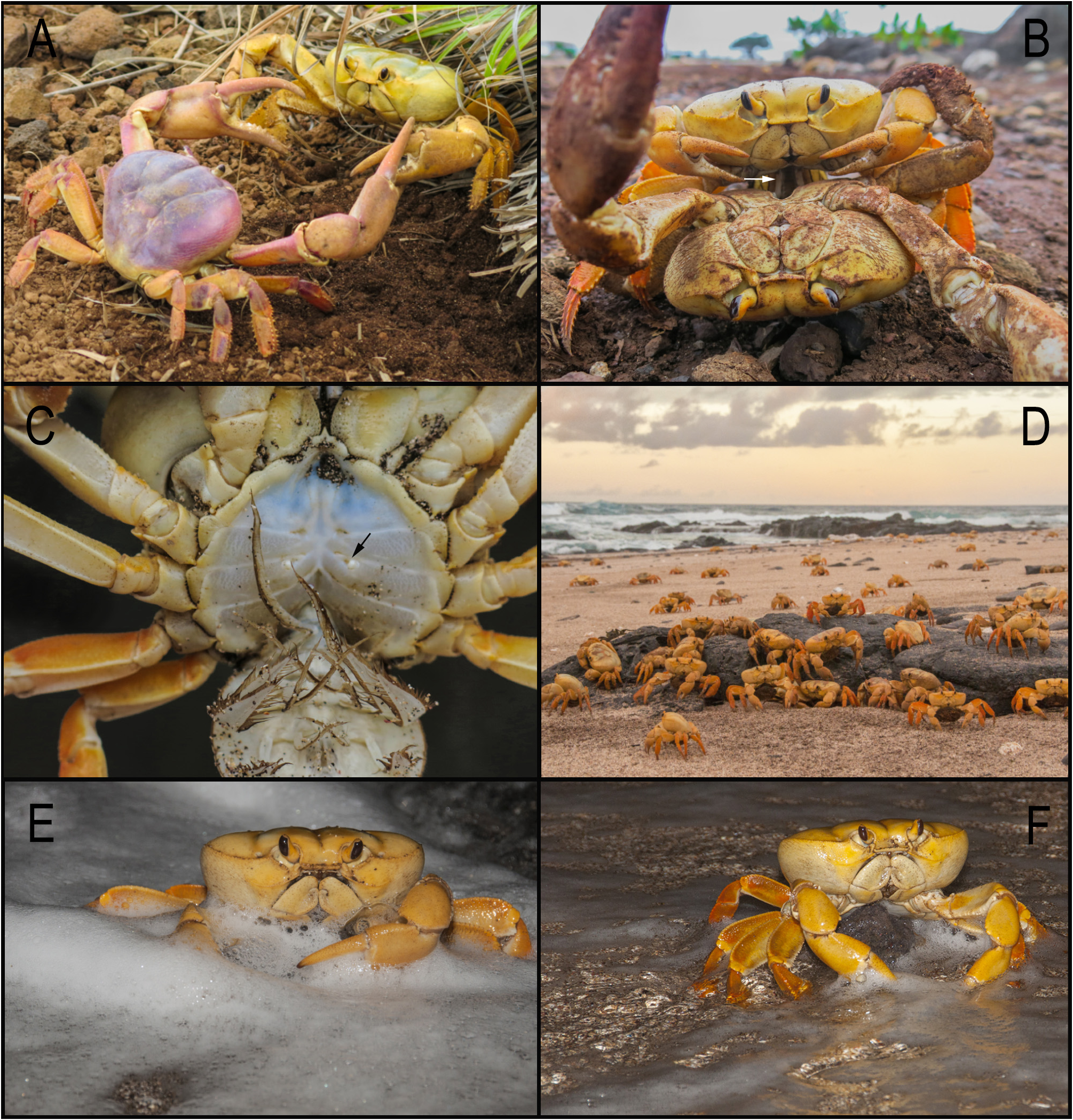

Ecological notes. Johngarthia lagostoma has a high level of independence from the aquatic environment. In Trindade, the crabs are found from upland habitats to heights of 600 m ( Fig. 46A View FIGURE 46 ). The crabs are more active during the night (moonless and dark moons nights are preferred) ( Fig. 46B View FIGURE 46 ), but they are not uncommon during daylight cool hours as well, and usually retreat to their burrows for protection during the heat hours ( Fig. 46C View FIGURE 46 ). The reduction of water loss is a basic requirement for a land crab. In J. lagostoma , the buccal frame is completely covered by the long and broadly operculiform third maxilliped ( Fig. 47A View FIGURE 47 ), whose merus extends anteriorly as far as to cover the remarkably small antenna and antennule, and the palp and maxilliped exopodite (devoid of flagellum) are both reduced in size and articulated at the maxilliped internal face, thus concealed to reduce water loss to a minimum ( Fig. 47B, C View FIGURE 47 ). Additionally, the maxillipeds leave a broad rhomboidal gap when closed, so that food can still enter the mouth and be processed by the mandibles ( Tavares 2002) ( Figs. 46D, H View FIGURE 46 ; 47A View FIGURE 47 ). The second and first maxillipeds also have the exopodites devoid of flagellae, which help to minimize water loss ( Fig. 47D, E View FIGURE 47 ). In Trindade, J. lagostoma occasionally visit freshwater streams, some times along with Grapsus grapsus (see Arai et al. 2017).

Feeding. Johngarthia lagostoma hunts for food, eat green leaves and decaying plant material ( Fig. 46H, I View FIGURE 46 ) (see also Baylis 1915), cannibalize conspecifics, and scavenge opportunistically ( Fig. 46G View FIGURE 46 ). It preys upon newborn sea turtles, seabirds’ chicks and eggs ( Fig. 46D–F View FIGURE 46 ), but also upon house mouses when it has the chance. During a Brazilian expedition to Trindade in 1916, a frigatebird endemic to Trindade (see Olson 2017) kept alive was killed and eaten by the crabs during the night ( Lobo 1919). Visibly, J. lagostoma rely primarily on plant material for food, as also attested by its massive, well calcified gastric mill ossicles (see Lima 2010), a feature consistent with the consumption of plant material (see also Linton & Greenaway 2007; Allardyce & Linton 2010).

Breeding behavior. Hartnoll and collaborators contributed a great deal to our knowledge of the breeding behavior and reproduction of J. lagostoma , essentially based on the crab population from the Ascension Island ( Hartnoll et al. 2006; 2007; 2009; 2010; 2014; Hartnoll 2009; 2010). The breeding patterns of the crab population from Trindade (this study) is consistent with the patterns described for Ascension and Rocas Atoll ( Teixeira 1996), but also show some contrasts as discussed hereafter. In Trindade (this study), mating and egg carrying have been observed from October to November, and hatching from November to December (observations made in 2014 and 2017). In Ascension, scattered data point to breeding migrations occurring from late January to May ( Hartnoll et al. 2006; 2009; 2010). Rodriguez-Rey et al. (2016) using mitochondrial markers found that almost half of the crabs from Trindade had haplotypes exclusive to this island. It is thus tempting to speculate that this might be aided in part by gene flow inhibited through differences in breeding seasons. Both sexes mature by 60 mm to 70 mm ( Hartnoll et al. 2010). Males fight each other with their chelipeds to access females ( Fig. 48A View FIGURE 48 ). During the mating, the male is usually under the female (sternum to sternum), which is held tightly by the male’s pereopods ( Fig. 48B View FIGURE 48 ), occasionally by the male’s chelipeds. The strong spines on the male’s pereopods dactyli and propodi help to hold the female in place ( Figs. 47F View FIGURE 47 , 48B View FIGURE 48 ). Both first gonopods are used for sperm transfer during the copulation ( Fig. 48B View FIGURE 48 ). The copulation occurs while the female is in hard-shelled condition either during daylight hours or at night ( Fig. 48B, C View FIGURE 48 ) (see also Hartnoll 2010; João et al. 2021). The first gonopod is provided subdistally with a corneous unguis with a distal opening ( Fig 47G View FIGURE 47 ). The populations in Ascension, Trindade and Martin Vaz are represented by two color morphs (yellow or orange and red or purple) ( Figs. 46B, G View FIGURE 46 , 48A View FIGURE 48 ) (see also Moreira 1920). Coloration is not sex specific. Contrary to Trindade and Ascension, where the pale morph is far more common, 56% of the crabs were red/purple in the Rocas Atoll ( Teixeira 1996). Hartnoll et al. (2006) speculated that differently from Ascension, where the pale coloration might be advantageous to survive the long-exposed breeding migration through bare arid lands, such is not the case in the much smaller Rocas Atoll. The long-exposed breeding migration hypothesis is not supported for Trindade, where the pale morph is far more common and there is no breeding migration through particularly arid land extensions. In Trindade (this study) and Ascension ( Hartnoll et al. 2006) males and females of both color morphs have been observed copulating with one another. During daylight hours prior to hatching, the ovigerous females remain concealed and do not take food. Near sunset, they migrate towards the beach ( Fig. 48D View FIGURE 48 ), but do not release their larvae until it is dark. Hartnoll et al. (2006) also recorded breeding activity mainly at night on Ascension ( April 2005). The ovigerous females enter the sea facing the incoming water (or side on) and release their eggs ( Fig. 48E, F View FIGURE 48 ) by vigorously shaking their body while helding the chelipeds spread out. Females carry about 72,000 eggs in average ( Hartnoll et al. 2010). The first zoea stage of J. lagostoma was described only recently ( Colavite et al. 2021; Lira et al. 2021). In Trindade (this study), spawning migration takes about three consecutive days, the most intenses being the first two days (observations in 2014 and 2017). Egg-laying peaked during the beginning of dark hours (between 6:00 pm and 7:30 pm, Trindade time). Very few males were seen late at night after spawning, but no copulation was observed. In Ascension, males and females migrate but females are far more common. The effect of moonlight and rainfall in the breeding of J. lagostoma is not obvious ( Hartnoll et al. 2006).

Recruitment. Apparently, the mass recruitment (well documented for other gecarcinids; Hicks 1985; Hartnoll & Clark 2006) is an exceptional event in J. lagostoma and the effect of the mortality is compensated by the regular trickle recruitment of juveniles. To the best of our knowledge, there is no record in the literature of mass recruitment on Trindade, Rocas Atoll and Fernando de Noronha. The small specimens in Table 4 View TABLE 4 were probably recruited on Trindade 1–3 years prior to their collection. Recruits are probably naturally infrequent even though they are more cryptic in habitat, hence more easily missed (see also Moreira 1920; Hartnoll et al. 2006). In Trindade, initial crab stages were found in galleries dug by the adults (observations made in 1987). The mass return to land in J. lagostoma must indeed be an exceptional event, as it was only once ( March 1963) recorded on Ascension ( Hartnoll et al. 2006). A study based on the examination of a large number of specimens from Ascension revealed very few immature crabs (<cw 60 mm) suggesting that the crab population on the island is an aging one ( Hartnoll et al. 2009). A similar study in regard to Trindade is necessary to provide managers with guidance in setting conservation goals.

Habitat protection and species conservation. Johngarthia lagostoma is omnivorous but rely heavily on the availability of vegetation for food and, occasionally, for shelter (see above under feeding) ( Fig. 46H, I View FIGURE 46 ). For more than three centuries domestic species introduced into Trindade (e.g. goats, pigs, sheep, donkey, guinea fowl, passerine bird, lizard, cat, mice, some of which became feral) greatly affected the terrestrial biota and reduced the forest cover by more than 80% ( Lobo 1919; Oliveira 1951; Alves et al. 2011). The eradication of most of these domestic species by the Brazilian Navy years ago led to the rapid revegetation. Hartnoll et al. (2006) clarified that the distribution of J. lagostoma in Ascension, normally limited to altitudes above 200 m is essentially the reflection of the subsistence of the vegetation, constrained to higher altitudes by human activities. Clearly, protection of the vegetation in Trindade is a key step towards the protection of J. lagostoma .

Predators and symbionts. The Atlantic Lesser Frigatebird, Fregata trinitatis , was observed to drop J. lagostoma from 3–4 m high to break and eat them ( Lobo 1919). Baylis (1915) found the oligochaete worm, Enchytraeus carcinophilus Baylis , living in the interior of the gill chamber of J. lagostoma collected between 450 m to 600 m of altitude on Trindade.

Manning & Chace (1990) summarized the scattered information accumulated for J. lagostoma in Ascension since Darwin (1839).

Remarks. H. Milne Edwards (1837: 27) described Johngarthia lagostoma (as Gecarcinus lagostoma ) upon material presented by Quoy and Gaimard and gave “l’Australasie” as the type locality (Jean Ren Constant Quoy and Joseph Paul Gaimard were naturalists aboard the voyage of the “L’Astrolabe”). H. Milne Edwards also described the Indo-West Pacific Gecarcoidea lalandii and stated “ Brésil ” as the type locality. This mistake was previously identified by several authors.

Judging from H. Milne Edwards’ (1837) statement (viz. “ Brésil ”), Trindade was likely candidate for the type locality of J. lagostoma as L’Astrolabe is known to have approached this island. However, according to L’Astrolabe’s commander Dumont D’Urville the expedition actually never landed in Trindade: “J’avais le dessein de tenter une excursion à la côte [of Trindade] avec les naturalistes; mais le ressac y était si violent, et la mer brisait avec tant de fureur sur tous ses points, que je ne jugeai pas à propos d’y hasarder une embarcation.” ( Dumont D’Urville, 1830: 70). Indeed, the vessel departed from Toulon on 22 April 1826 but contrary winds delayed the expedition so long that L’Astrolabe approached Trindade only three months later, on 31 July. From there, L’Astrolabe sailed non-stop to Port du Roi Georges (currently Albany, western Australia) where it arrived on 7 October. In her way back to France in 1829, L’Astrolabe stoped at the Ascension Island where numerous natural history specimens were collected ( Quoy & Gaimard, 1833), among which possibly the material used by H. Milne Edwards (1837) in the original description of J. lagostoma . Therefore, we agree with Manning & Chace’s (1990) suggestion that Ascension is most probably the type locality of J. lagostoma .

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

InfraOrder |

Brachyura |

|

SuperFamily |

Grapsoidea |

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Johngarthia lagostoma (H. Milne Edwards, 1837)

| TAVARES, MARCOS & MENDONÇA, JOEL BRAGA DE JR. 2022 |

Gecarcinus lagostoma

| H. Milne Edwards 1837: 27 |