Ceraphronoidea

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1093/isd/ixy015 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:68249DCE-5520-4415-85D1-80CCA002A48D |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03DD3922-C550-C720-FCA1-04E2FD10FCA3 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Ceraphronoidea |

| status |

|

The presence of a single marginal vein equipped with triangular elements along the anterior forewing margin is the most obvious unique trait of the superfamily (Mikó et al. 2018). The marginal vein has a less-sclerotized short portion (fenestra) in the middle of the wing that is also present in numerous other hymenopteran taxa and is usually referred to as the costal break ( Fig. 9B View Fig ). The costal break allows the wing to bend along the radial flexion line that is continuous with the break ( Danforth 1989, Prentice 1989).

The pterostigma in Hymenoptera is structurally, positionally and probably even functionally different from that of Odonata ( Arnold 1963). It is located just distally of the costal break and is believed to facilitate aerodynamically-important localized wing deformations due to the bending of the wing along the posterior radial flexion line ( Danforth 1989). This bending is crucial for high Reynolds number flights. Bending along flexion lines can be challenging in smaller wings; this may explain why smaller hymenopterans possess a larger pterostigma relative to the overall wing surface ( Danforth 1989,

Prentice 1989). Hymenopteran lineages with the smallest specimens and wings, however, lack a pterostigma (e.g., Chalcidoidea). One possible explanation for this phenomenon might be the change in flight dynamics to a low Reynolds number ‘clap and fling’ method where the above-mentioned wing deformations may not be as relevant ( Danforth 1989, Prentice 1989).

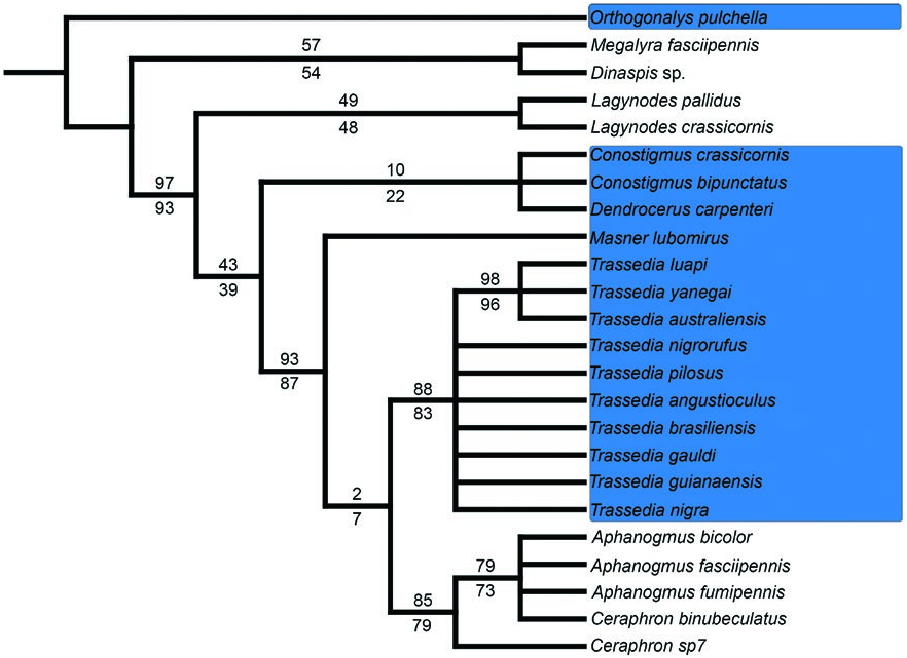

The presence of the pterostigma is an obvious character that defines monophyletic lineages within Ceraphronoidea (2, Mikó et al. 2013) and has been the subject of speculations to resolve relationships within the superfamily ( Masner and Dessart 1967, Mikó and Deans 2009). Lagynodinae and most Ceraphronidae lack a pterostigma, while Megaspilinae and two ceraphronid lineages, Masner and Trassedia , possess a pterostigma. The presence of the pterostigma distinctly corresponds to body size, as megaspilines include the largest megaspilids (e.g., Megaspilus Westwood, 1829 ) and Trassedia specimens are the largest ceraphronids. The smallest members of Ceraphronoidea are from the lineages that lack a pterostigma: Lagynodinae and sensu stricto Ceraphronidae ( Fig. 2 View Fig ). Our morphology-based preliminary analyses failed to recover basal ceraphronoid relationships ( Fig. 2 View Fig , Mikó et al. 2013) therefore it is still questionable if a pterostigma has been lost or gained independently during the course of evolution. Whether these changes coincide or are driven by a switch to ‘clap and fling’ flight is yet to be explored.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.