Nanotyrannus (Gilmore, 1946)Tyrannosaurus rex, Osborn, Hell Creek Fm. & Custer, 1905

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2015.12.016 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4715039 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03DC7E37-F05A-FFA3-FF49-FE18FBD9FA1D |

|

treatment provided by |

Jeremy |

|

scientific name |

Nanotyrannus Tyrannosaurus rex |

| status |

|

The phylogenetic distribution of the lateral dentary groove was investigated to determine the polarity of the character, to interpret the implication of its losses, and to assess its potential as a diagnostic feature for re-classifying the position of “Jane” (BMR P2002.4.1) and other specimens labeled Nanotyrannus within Tyrannosauroidea. “Jane” is clearly a tyrannosaurid ( Brusatte et al., 2010), but its taxonomic affiliation has been highly disputed ( Erickson et al., 2006; Snively and Russell, 2007; Larson, 2008; Henderson and Harrison, 2008; Peterson et al., 2009; Larson, 2013a). The debate over “Jane” is a smaller part of a larger debate about the validity of Nanotyrannus lancensis as a separate genus ( Bakker et al., 1988). Three specimens have taken center stage in this debate: “ Jane ”, the holotype specimen of N. lancensis ( CMNH 7531 ), and the theropod described as one of the “Dueling Dinosaurs” ( BHI 6437 ; Larson, 2013b). The debate presently rests on three competing hypotheses, either that 1) Nanotyrannus stands as a valid taxon ( Currie, 2003a; Larson, 2013a); 2) these individuals represent the taxon Tyrannosaurus lancensis ( Currie et al., 2005) ; or 3) these individuals are juvenile Tyrannosaurus rex ( Carr, 1999; Brochu, 2003; Carr and Williamson, 2004; Holtz, 2004). A goal of this study is to attempt to clarify the relationship of N. lancensis with other tyrannosaurids using the dentary groove and other cranial characters ( Larson, 2013a).

2. Materials and methods

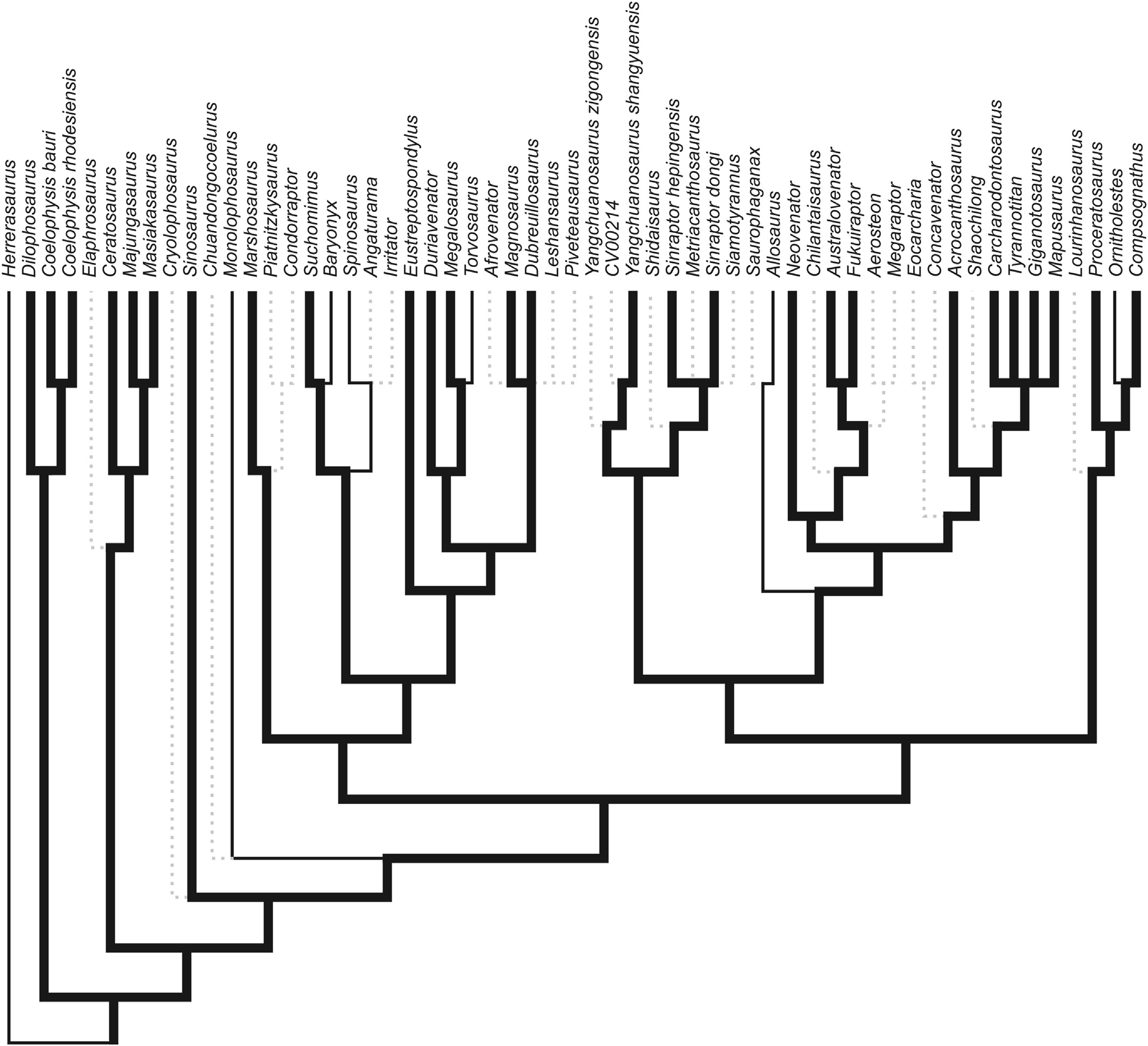

We investigated 92 theropod taxa for presence or absence of a groove on the lateral surface of the dentary ( Fig. 1 View Fig ). We also examined photographs of the crocodylomorph Shuvosaurus , the early dinosaurs Herrerasaurus and Staurikosaurus , and the sauropodomorphs Eoraptor, Leyesaurus, Pampadromaeus , and Panphagia for comparison. Sampled taxa and reviewed published records are delineated in the supplemental data View . We relied on descriptions of holotypes whenever possible, to avoid controversy as to taxonomic assignment. Some sampled specimens are the subject of debate (e.g. “Jane”) and the attribution of some unpublished specimens is controversial (e.g., assignment of specimens to Spinosaurus aegypticus). When such published descriptions did not include photographs of the specimen(s) or presence or absence of the groove was not unambiguously depicted in an illustration, we examined images of additional congeneric specimens, as available.

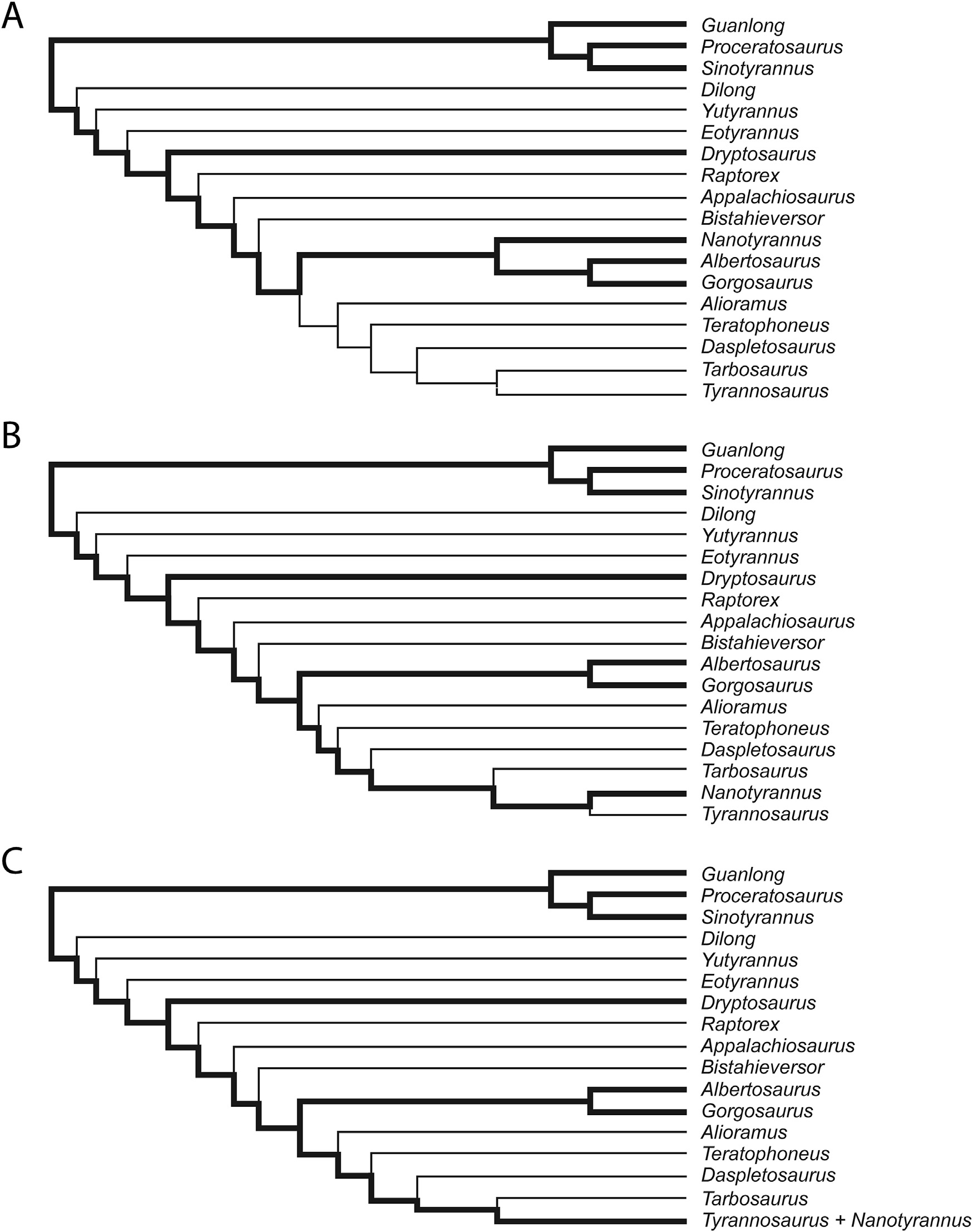

Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using TNT v1.1 ( Goloboff et al., 2008). We utilized the methodology and character matrix of Brusatte et al. (2010), and modified it only by adding Nanotyrannus to the character matrix and coding the dentary groove as present in Dryptosaurus, without modification of any other characters. The character matrix is included in the supplemental file View . We coded the character matrix for Nanotyrannus based on personal observations of skull of “Jane” at the Burpee Museum. Presence of the groove is character 176 of Brusatte et al. (2010) and character 124 of Carrano et al. (2012). We traced the most parsimonious occurrence of this character on the branches of these previously published cladograms to evaluate its use as a diagnostic character in theropods and to evaluate competing phylogenetic hypotheses ( Figs. 2 View Fig - 3 View Fig ). The most parsimonious result of this study is reported in Fig. 3A View Fig .

Institutional Abbreviations―LACM, Los Angeles County Museum, Los Angeles, CA; BHI, Black Hills Institute of Geological Research, Inc., Hill City, SD; BMR, Burpee Museum, Rockford, IL; BSP, Bayerische Staatsammlung für Paläontologie und historische Geologie, Munich, Germany; CMNH, Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Cleveland, OH; FMNH, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL; KUVP, University of Kansas Museum of Natural History and Biodiversity Institute, Lawrence, KS; NMMNH, New Mexico Museum of Natural History, Albuquerque, NM; TCM, The Children's Museum, Indianapolis, IN.

3. Results

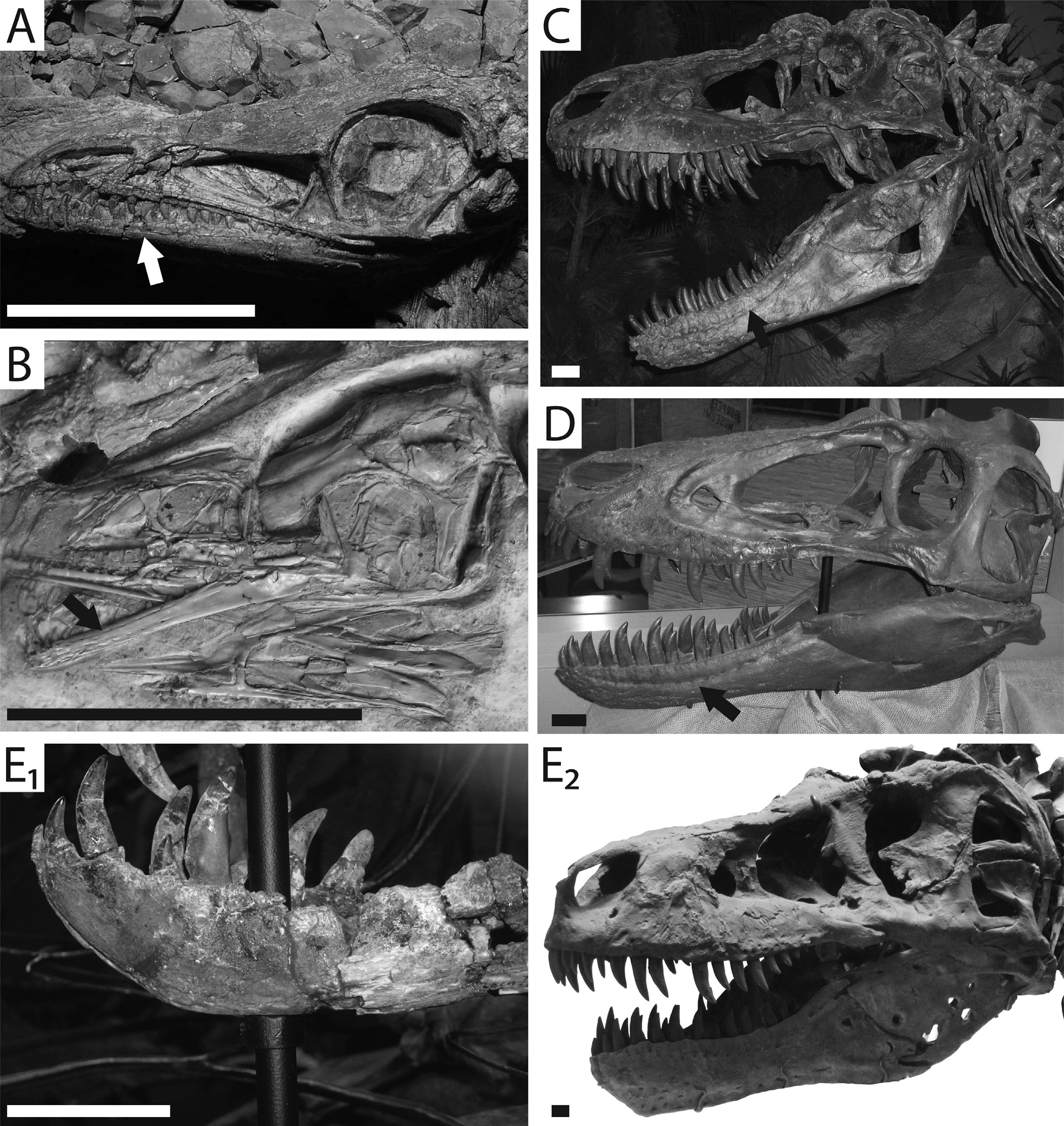

The dentary groove is a unique structure with multiple pores aligned within the depression and sub-equally spaced. The groove originates near the anterior portion of the bone from a position approximately underneath the 2nd to 4th dentary alveolus. It extends caudally along the lateral surface, terminating near the end of the tooth row ( Fig. 1 View Fig ; see also figure 1a of Sampson and Witmer, 2007). This groove does not extend beyond the dentary in examined theropods. This contrasts with the sauropodomorphs Eoraptor and Panphagia , wherein a groove extends onto the surface of the surangular and terminates in a large foramen. Multiple pores were noted along the length of the groove in theropod dinosaurs.

The dentary groove was present on 48 of 92 sampled theropod taxa (see supplemental data View ). No groove was observed in the crocodylomorph Shuvosaurus or the early dinosaur Herrerasaurus , strengthening the hypothesis that this feature is unique to theropod taxa. The groove was also not observed in Daemonosaurus or Tawa, the most primitive true theropods that we sampled. Allosaurus , Baryonyx , Monolophosaurus , Ornitholestes , Spinosaurus , and Torvosaurus were the only observed pre-Tyrannoraptoran taxa that reverted to the primitive state ( Fig. 2 View Fig ).

The single most parsimonious tree recovered by our phylogenetic analysis of tyrannosauridae is reported in Fig. 3A View Fig . The minimum tree length was found after 5 replicates, and the most parsimonious tree has a length of 561. Nanotyrannus was recovered as the sister taxon to the Albertosaurinae . We recovered the same topology as reported by Brusatte et al. (2010), except that the Proceratosauridae was recovered as a polytomy. The most parsimonious tree we produced resulted in a polytomy, regardless of whether Nanotyrannus was included or not. Alternative nonparsimonious tree topologies based on our result but reflecting the proposed relationships of Nanotyrannus among the Tyrannosauroidea sensu Currie (2003a) and Carr (1999) are presented for comparison in Fig. 3B and C View Fig respectively.

We investigated undisputed Tyrannosaurus rex material pertaining to the different life stages (i.e., juvenile, subadult, and adult of Carr and Williamson, 2004). The dentary of the smallest known juvenile of T. rex (LACM 28471) lacks the dentary groove. Although its dentary is fragmentary, the anterior portion is preserved, and examination failed to reveal the presence of a dentary groove. None of the T. rex specimens examined (LACM 28471, LACM 23845, LACM 150167, KUVP 155809, FMNH PR2081) possessed the groove.

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of presence of dentary groove

The dentary groove is present in 33 of 41 (80%) of the pre- Tyrannoraptoran theropods sampled here. We interpret only 6 reversals responsible for groove losses ( Fig. 2 View Fig ). The presence of this groove is therefore a character primitive for nearly all early theropods. Given the absence of the groove in the theropod clades which include Daemonosaurus and Tawa, the groove first evolved in the earliest common ancestor of the Neotheropoda. Within highly derived theropods, the dentary groove is present in some members of the Maniraptora. A similar foramina-bearing groove has been considered a synapomophy of Troodontidae ( Makovicky and Norell, 2004) . As such, it is present on all sampled troodontids, but limited to the posterior portion of the dentary. A groove was also observed in the dromaeosaurids Acheroraptor , Austroraptor and Buitreraptor . In Maniraptora, the groove appears to increase in height posteriorly (i.e., grows closer to the tooth row), creating a wedge-shaped appearance, rather than the linear shape of the groove in other theropod dinosaurs. In the troodontids, Acheroraptor , and Austroraptor , the groove originates beneath the middle of the tooth row and extends nearly to the posterior end of the dentary. We interpret this difference as truly morphological and do not consider the groove found in the Maniraptora to be homologous with the dentary groove of other theropods. Currie (1987) and Makovicky and Norell (2004) have interpreted a neurovascular function for this troodontid groove and its pores, an interpretation that we do not challenge.

Few tyrannosauroids retain this groove. “Jane” clearly has this groove ( Fig. 1D View Fig ) as does BHI 6437 . The condition of the Nanotyrannus holotype is unclear, as its jaws are occluded and the groove-bearing portion of the dentary obscured. The only other tyrannosauroids that possess this groove are Dryptosaurus aquilunguis and the Albertosaurinae : Gorgosaurus libratus and Albertosaurus sarcophagus.

4.2. Possible implications of beak formation and dentary groove absence

There are several dentary groove absences that occur simultaneously with the presence of a beak or edentulous jaws. The beaked ceratosaur Limusaurus, ornithomimids ( Nqwebasaurus and Shenzhousaurus), therizinosaurs (Erlikosaurus and Jiangchanosaurus), oviraptorosaurs ( Caudipteryx and Chirostenotes ) and all sampled birds lack the dentary groove. The jaw structure of Limusaurus has been completely modified into a beak and the dentary of Limusaurus even lacks any foramina on its lateral surface. Simply modifying the mandible into a beak, however, does not account for this absence of the groove. Only the anterior of the upper jaws were beak-like in Jiangchanosaurus, in which only the premaxillae were considered to have been covered by a rhamphotheca ( Pu et al., 2013). Jiangchanosaurus does not have a groove. The toothed birds Archaeopteryx, Hesperornis, Ichthyornis, and Parahesperornis also lack a dentary groove, despite being beakless or only having an incipient beak.

Adoption of herbivory is a reasonable hypothesis for the evolutionary loss of serrated teeth from the jaws in favor of edentulous jaws or beaks. One explanation is that that the dentary groove played a role in predatory behavior and that the groove was lost in these theropods because carnivory was abandoned. Ornithomimids ( Kobayashi et al., 1999; Norell et al., 2001) and therizinosaurs ( Zanno et al., 2009) are both postulated to have been herbivorous. Oviraptorosaurs may have been predominately herbivorous ( Ji et al., 1998; Xu et al., 2002), although they may have taken prey or scavenged under rare circumstances ( Norell et al., 1994). Analysis of jaw mechanics in theropod dinosaurs clearly demonstrates the dissimilarity of oviraptosaurs and predatory theropods ( Brusatte et al., 2012b). The lack of the dentary groove is taken as further evidence that they may not have been active predators. The possibility that the common ancestor of Ornithomimosaurs, Oviraptorosaurs, and Therizinosaurs also lacked a dentary groove cannot be overlooked, especially given the absence of a groove in most other maniraptorans. While the presence of a beak does not necessarily indicate herbivorous lifestyle―as squid, placoderm fish and birds of prey all utilize beaks in predatory behavior―why a well-adapted predator like a theropod would evolve a beak to bolster a predatory lifestyle is unclear, and an interpretation of herbivory in this context is more parsimonious.

4.3. Absence of groove in tyrannosauroids

There are numerous tyrannosauroids that lacked the dentary groove. Assuming maximum parsimony for the distribution of the dentary groove, we must interpret several of these as independent losses. One potential explanation for the absence of the groove in certain taxa might be that the nerves and blood vessels accommodated by the groove occurred superficial to the dentary rather than along its surface. Another potential explanation for the loss of the groove in various tyrannosaurids is to enhance jaw strength. The groove could potentially serve as a point of weakness: forcemodeling experiments on the mandible of Erlikosaurus demonstrate higher stress levels along the line of mandibular foramina during simulated bites ( Lautenschalger et al., 2013). The groove was likely eliminated as the cortical bone of the dentary was thickened to accommodate strong bite forces ( Therrien et al., 2005). Loss of the groove would therefore be advantageous from a mechanical perspective for the largest tyrannosaurids. Snively et al. (2006) hypothesized that tyrannosaurines had stronger bite forces compared to albertosaurines and carnosaurs, due to vaulting of the skull, enhanced fusion of the cranial bones and skull kinematics. Tyrannosaurines likely consumed greater amounts of bone relative to smaller theropods ( Fiorillo, 1991; Erickson and Olson, 1996; Snively et al., 2006). That makes sense, given that (1) observation of modern ecosystems demonstrates that predators with stronger bite forces tend to consume more portions of the prey ( Van Valkenburgh, 1996) and (2) the presence of prey items (e.g., ceratopsians) in the Cretaceous which possess bony frills. Large tyrannosaurids used a “puncture and pull” feeding strategy ( Bakker, 1986; Molnar and Farlow, 1990; Erickson and Olson, 1996) which required that the teeth penetrate bone, in order to effectively anchor the jaws into the prey. This feeding behavior has been interpreted from bite marks on ceratopsians ( Erickson and Olson, 1996). Other theropods (e.g, Allosaurus , Giganotosaurus ) may have instead relied on cranial kinesis and thin, slicing teeth to wound their prey ( Paul, 1988; Rayfield et al., 2001; Therrien et al. 2005), instead of ripping large portions (e.g., limbs) from the body of the prey. Since the groove conducted a nerve along the surface of the dentary, a powerful bite may also have been intrinsically painful. The nerve may have been reduced and the groove therefore eliminated, as more powerful biting force evolved in tyrannosaurids. A biomechanical explanation for the loss of the groove is appealing, because large carcharodontosaurids were stratigraphically contemporaneous with tyrannosaurines and, in some cases, were larger than tyrannosaurines. Thus increase in size alone is not sufficient to explain the loss of the groove.

The variable distribution of the groove among tyrannosaurids may explain the seemingly incompatible cohabitation ( Farlow and Pianka, 2003) of Daspletosaurus (in which a groove is absent) with Gorgosaurus and Albertosaurus (in which the groove is present). Daspletosaurus may have been adapted to eating prey that required powerful bites to subdue or consume, whereas the albertosaurines were more lightly built predators that perhaps preferred less robust prey. This is in keeping with Russell's (1970) hypothesis that albertosaurines preyed on hadrosaurs, whereas Daspletosaurus specialized on ceratopsians. Tyrannosaurines are known to have taken hadrosaurs as prey items ( Varricchio, 2001; DePalma et al., 2013). Rather than invalidate our hypothesis, this merely is evidence that tyrannosaurines were large, powerfully built predators that were capable of taking any suitable prey items in their environment. This explanation is consistent with the mechanical hypothesis we pose here.

A potential flaw in this hypothesis is the absence of the groove in many smaller tyrannosauroid genera, such as Alioramus, Dilong, and Eotyrannus. While an examination of the bite force of these taxa is beyond the scope of the present study, it may be the case that these smaller tyrannosauroids were also exerting relatively high bite forces on their prey or otherwise needed to strengthen their jaws for successful food acquisition.

4.4. Interpreting the identity of “ Jane ” and the validity of Nanotyrannus

The mosaic distribution of the dentary groove within Tyrannosauroidea allows an opportunity to use the occurrence of this character to determine the relationship of the embattled Nanotyrannus to other tyrannosaurs. Tyrannosaurus rex lacks this groove, whereas it is a distinct character in “Jane” and the other Nanotyrannus lancensis specimens in which the dentary is visible. The occurrence of the dentary groove in N. lancensis , but not in T. rex , is itself independent evidence of separation of these two taxa. The presence of the groove stands with more than 30 other skeletal characters as evidence to separate Nanotyrannus from Tyrannosaurus ( Larson, 2013a) .

A frequent point of contention in the literature for using skeletal characters to differentiate Nanotyrannus and Tyrannosaurus is the possibility of ontogenetic variation, the chance that characters become altered as an individual matures into adulthood. While the size, orientation, and depth of cranial fossa and such openings as the orbits in tyrannosaurs, as well as tooth count and morphology, have been interpreted to be ontogenetically variable ( Carr, 1999), these interpretations have been questioned ( Currie, 2003a; Larson, 2013a). The argument that the dentary groove is an ontogenetically variable character is unappealing for several reasons. First, if this feature corresponds to a system of nerves enervating the mandible, a dramatic change (e.g., metamorphosis) would need to be invoked to explain the loss of this feature through maturation. Second, there are other undisputed T. rex specimens, representing juvenile ( LACM 28471 , LACM 23845 ) and subadult ( LACM 150167 , KUVP 155809 ) stages, that lack this groove. The adult form (e.g., FMNH PR2081 ) lacks this groove.

As all Tyrannosaurus rex specimens we investigated lack a dentary groove, even in juvenile and subadult individuals, and all Nanotyrannus specimens we investigated possess a dentary groove, this seems to suggest that the groove is not variable in a single species and that it does not change during ontogeny. The presence or absence of a groove may further be sufficient to diagnose one taxon from another taxon. The most reasonable explanation for this data is that N. lancenesis is a distinct taxon and not a juvenile form of T. rex .

The dentary groove is such a phylogenetically conservative character (i.e., only five losses outside of Tyrannoraptora) that the presence or absence of the groove in tyrannosaurids seems a useful taxonomic character. Nanotyrannus has been suggested to be similar to Gorgosaurus , based on the presence of numerous cranial and dental characteristics ( Larson, 2013a). Interestingly, CMNH 7531 was originally described as a species of Gorgosaurus ( Gilmore, 1946) . The presence of the dentary groove in Nanotyrannus seems to further confirm its affinity with Albertosaurinae rather than Tyrannosaurinae . Albertosaurinae is defined as the tyrannosaurs possessing: an antorbital cavity that reaches the nasomaxillary suture, lateral surface of nasal excluded from the antorbital vacity, and a dorsally-oriented, triangular corneal process of the lacrimal ( Holtz, 2004). Currie (2003b) defined Albertosaurinae as possessing, in contrast to Tyrannosaurinae , short and low skulls, shorter ilia, longer tibiae, longer metatarsals and longer toes, a definition Nanotyrannus meets. Larson (2013a) presented more than 30 skeletal characters that separate Nanotyrannus from Tyrannosaurus , with the following characters possibly uniting Nanotyrannus and the albertosaurines: greater dentary tooth counts, contact of the maxillary fenestra with the rostral margin of the antorbital fossa, a medial post-orbital fossa and an ectopterygoid pneumatic foramina bounded by a thick lip. Albertosaurines may also be regarded as having more circular than ovoid orbits. We propose that the presence of the dentary groove be added to the list of diagnostic albertosaurine characters, as it is a character that is lost in Tyrannosaurinae . We therefore propose that Nanotyrannus should be regarded as a member of Albertosaurinae .

Fig. 3 View Fig shows three potential interpretations of the phylogeny of Tyrannosauroidea. Nanotyrannus has been previously suggested to be either (1) a valid taxon distinct from Tyrannosaurus ( Fig. 3A View Fig ; Larson, 2008; Larson, 2013a), (2) the sister taxon to Tyrannosaurus , either as Tyrannosaurus lancensis ( Currie et al., 2005) or as Nanotyrannus ( Fig. 3B View Fig ; Currie et al., 2003), or (3) even a juvenile Tyrannosaurus ( Fig. 3C View Fig ; Brusatte et al., 2010). The most parsimonious distribution of the dentary groove found in this study ( Fig. 3A View Fig ) places Nanotyrannus as sister to the Albertosaurinae ( Gorgosaurus + Albertosaurus ). The Nanotyrannus + Tyrannosaurus hypothesis ( Fig. 3B View Fig ) requires five additional independent losses of the dentary groove, more than the tree which places Nanotyrannus closer to Albertosauriane. The hypothesis that Nanotyrannus is a juvenile Tyrannosaurus ( Fig. 3C View Fig ) requires four additional independent losses, as well as requiring an ontogenetic explanation for why juvenile T. rex possesses the character absent in adults. The fact that there are specimens interpreted as juvenile and subadult T. rex that lack the dentary groove should render that hypothesis completely unsupportable.

5. Conclusions

The occurrence of the dentary groove in theropod dinosaurs serves as a useful feature for determining relationships and inferring the validity of the disputed taxon Nanotyrannus . The groove appears early in the theropod record and is a ubiquitous character for the duration of the Jurassic and Early Cretaceous. For the 92 theropod taxa investigated in this study, 48 possess this feature. As 80% of basal theropods possess this groove, it could be considered a defining character of theropod dinosaurs, lost in only a handful of lineages. While loss of the groove did not appear to result from the evolution of beaks in different theropod clades, it may have been one of many evolutionary changes that occurred which strengthened the jaws of tyrannosaurids. This feature has also proved useful for interpreting relationships among tyrannosauroids, which have a mosaic distribution of this character. Nanotyrannus clearly presents the dentary groove, whereas Tyrannosaurus rex lacks this feature. Without a modern analog that demonstrates the loss of such a groove through maturation, accepting that this feature is lost through ontogeny is speculative. “Jane”, and the other specimens referred to Nanotyrannus , therefore would not be examples of juvenile Tyrannosaurus , and stand alone as a distinct genus. Nanotyrannus should further be considered sister to the Albertosaurinae , rather than the Tyrannosaurinae , as they are the only other clade of large tyrannosaurs to possess this groove. This feature, in addition to many other cranial characters, makes an alignment of Nanotyrannus with the albertosaurines preferred.

A frequent point of contention in the literature for using skeletal characters to differentiate Nanotyrannus and Tyrannosaurus is the possibility of ontogenetic variation, the chance that characters become altered as an individual matures into adulthood. While the size, orientation, and depth of cranial fossa and such openings as the orbits in tyrannosaurs, as well as tooth count and morphology, have been interpreted to be ontogenetically variable ( Carr, 1999), these interpretations have been questioned ( Currie, 2003a; Larson, 2013a). The argument that the dentary groove is an ontogenetically variable character is unappealing for several reasons. First, if this feature corresponds to a system of nerves enervating the mandible, a dramatic change (e.g., metamorphosis) would need to be invoked to explain the loss of this feature through maturation. Second, there are other undisputed T. rex specimens, representing juvenile ( LACM 28471 , LACM 23845 ) and subadult ( LACM 150167 , KUVP 155809 ) stages, that lack this groove. The adult form (e.g., FMNH PR2081 ) lacks this groove.

As all Tyrannosaurus rex specimens we investigated lack a dentary groove, even in juvenile and subadult individuals, and all Nanotyrannus specimens we investigated possess a dentary groove, this seems to suggest that the groove is not variable in a single species and that it does not change during ontogeny. The presence or absence of a groove may further be sufficient to diagnose one taxon from another taxon. The most reasonable explanation for this data is that N. lancenesis is a distinct taxon and not a juvenile form of T. rex .

The dentary groove is such a phylogenetically conservative character (i.e., only five losses outside of Tyrannoraptora) that the presence or absence of the groove in tyrannosaurids seems a useful taxonomic character. Nanotyrannus has been suggested to be similar to Gorgosaurus , based on the presence of numerous cranial and dental characteristics ( Larson, 2013a). Interestingly, CMNH 7531 was originally described as a species of Gorgosaurus ( Gilmore, 1946) . The presence of the dentary groove in Nanotyrannus seems to further confirm its affinity with Albertosaurinae rather than Tyrannosaurinae . Albertosaurinae is defined as the tyrannosaurs possessing: an antorbital cavity that reaches the nasomaxillary suture, lateral surface of nasal excluded from the antorbital vacity, and a dorsally-oriented, triangular corneal process of the lacrimal ( Holtz, 2004). Currie (2003b) defined Albertosaurinae as possessing, in contrast to Tyrannosaurinae , short and low skulls, shorter ilia, longer tibiae, longer metatarsals and longer toes, a definition Nanotyrannus meets. Larson (2013a) presented more than 30 skeletal characters that separate Nanotyrannus from Tyrannosaurus , with the following characters possibly uniting Nanotyrannus and the albertosaurines: greater dentary tooth counts, contact of the maxillary fenestra with the rostral margin of the antorbital fossa, a medial post-orbital fossa and an ectopterygoid pneumatic foramina bounded by a thick lip. Albertosaurines may also be regarded as having more circular than ovoid orbits. We propose that the presence of the dentary groove be added to the list of diagnostic albertosaurine characters, as it is a character that is lost in Tyrannosaurinae . We therefore propose that Nanotyrannus should be regarded as a member of Albertosaurinae .

Fig. 3 View Fig shows three potential interpretations of the phylogeny of Tyrannosauroidea. Nanotyrannus has been previously suggested to be either (1) a valid taxon distinct from Tyrannosaurus ( Fig. 3A View Fig ; Larson, 2008; Larson, 2013a), (2) the sister taxon to Tyrannosaurus , either as Tyrannosaurus lancensis ( Currie et al., 2005) or as Nanotyrannus ( Fig. 3B View Fig ; Currie et al., 2003), or (3) even a juvenile Tyrannosaurus ( Fig. 3C View Fig ; Brusatte et al., 2010). The most parsimonious distribution of the dentary groove found in this study ( Fig. 3A View Fig ) places Nanotyrannus as sister to the Albertosaurinae ( Gorgosaurus + Albertosaurus ). The Nanotyrannus + Tyrannosaurus hypothesis ( Fig. 3B View Fig ) requires five additional independent losses of the dentary groove, more than the tree which places Nanotyrannus closer to Albertosauriane. The hypothesis that Nanotyrannus is a juvenile Tyrannosaurus ( Fig. 3C View Fig ) requires four additional independent losses, as well as requiring an ontogenetic explanation for why juvenile T. rex possesses the character absent in adults. The fact that there are specimens interpreted as juvenile and subadult T. rex that lack the dentary groove should render that hypothesis completely unsupportable.

5. Conclusions

The occurrence of the dentary groove in theropod dinosaurs serves as a useful feature for determining relationships and inferring the validity of the disputed taxon Nanotyrannus . The groove appears early in the theropod record and is a ubiquitous character for the duration of the Jurassic and Early Cretaceous. For the 92 theropod taxa investigated in this study, 48 possess this feature. As 80% of basal theropods possess this groove, it could be considered a defining character of theropod dinosaurs, lost in only a handful of lineages. While loss of the groove did not appear to result from the evolution of beaks in different theropod clades, it may have been one of many evolutionary changes that occurred which strengthened the jaws of tyrannosaurids. This feature has also proved useful for interpreting relationships among tyrannosauroids, which have a mosaic distribution of this character. Nanotyrannus clearly presents the dentary groove, whereas Tyrannosaurus rex lacks this feature. Without a modern analog that demonstrates the loss of such a groove through maturation, accepting that this feature is lost through ontogeny is speculative. “Jane”, and the other specimens referred to Nanotyrannus , therefore would not be examples of juvenile Tyrannosaurus , and stand alone as a distinct genus. Nanotyrannus should further be considered sister to the Albertosaurinae , rather than the Tyrannosaurinae , as they are the only other clade of large tyrannosaurs to possess this groove. This feature, in addition to many other cranial characters, makes an alignment of Nanotyrannus with the albertosaurines preferred.

Bakker, R. T., 1986. The Dinosaur Heresies. William and Morrow, New York, New York, 481 pp.

Bakker, R. T., William, M., Currie, P., 1988. Nanotyrannus, a new genus of pygmy tyrannosaur, from the Latest Cretaceous of Montana. Hunteria 1, 1 - 28.

Brochu, C. A., 2003. Osteology of Tyrannosaurus rex: insights from a nearly complete skeleton and high-resolution computed tomographic analysis of the skull. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir 7, 1 - 138.

Brusatte, S. L., Norell, M. A., Carr, T. D., Erickson, G. M., Hutchinson, J. R., Balanoff, A. M., Bever, G. S., Choiniere, J. N., Makovicky, P. J., Xu, X., 2010. Tyrannosaur paleobiology: new research on ancient exemplar organisms. Science 329, 1481 - 1485.

Brusatte, S. L., Sakamoto, M., Montanari, S., Harcourt Smith, W. E. H., 2012 b. The evolution of cranial form and function in theropod dinosaurs: insights from geometric morphometrics. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 25, 365 - 377.

Carr, T. D., 1999. Craniofacial ontogeny in Tyrannosauridae (Dinosauria, Coelurosauria). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 19, 497 - 520.

Carr, T. D., Williamson, T. E., 2004. Diversity of late Maastrichtian Tyrannosauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from western North America. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 142, 479 - 523.

Carrano, M. T., Benson, R. B. J., Sampson, S. D., 2012. The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 10, 211 - 300.

Currie, P. J., 1987. Bird-like characteristics of the jaws and teeth of troodontid theropods (Dinosauria, Saurischia). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 7, 72 - 81.

Currie, P. J., 2003 a. Cranial anatomy of tyrannosaurid dinosaus from the Late Cretaceous of Alberta, Canada. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 48, 191 - 226.

Currie, P. J., 2003 b. Allometric growth in tyrannosaurids (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of North America and Asia. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 40, 651 - 665.

Currie, P. J., Hurum, J. H., Sabath, K. L., 2003. Skull structure and evolution in tyrannosaurid dinosaurs. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 48, 227 - 234.

Currie, P. J., Henderson, M., Horner, J. R., Williams, S. A., 2005. On tyrannosaur teeth, tooth positions and the taxonomic status of Nanotyrannus lancensis. In: The Origin, Systematics, and Paleobiology of Tyrannosauridae Symposium. Abstracts: 19.

DePalma, R. A., Burnham, D. A., Martin, L. D., Rothschild, B. M., Larson, P. L., 2013. Physical evidence of predatory behavior in Tyrannosaurus rex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 110, 12560 - 12564.

Erickson, G. M., Olson, K. H., 1996. Bite marks attributable to Tyrannosaurus rex: preliminary description and implications. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 16, 175 - 178.

Erickson, G. M., Currie, P. J., Inouye, B. D., Winn, A. A., 2006. Tyrannosaur life tables: an example of nonavian dinosaur population biology. Science 313, 213 - 217.

Farlow, J. O., Pianka, E. R., 2003. Body size overlap, habitat partitioning and living space requirements of terrestrial vertebrate predators: implications for the paleoecology of large theropod dinosaurs. Historical Biology 16, 21 - 40.

Fiorillo, A. R., 1991. Prey utilization by predatory dinosaurs. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology & Palaeoecology 88, 157 - 166.

Gilmore, C. W., 1946. A new carnivorous dinosaur from the Lance formation of Montana. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 106 (13), 1 - 19.

Goloboff, P. A., Farris, J. S., Nixon, K. C., 2008. TNT, a free program for phylogenetic analysis. Cladistics 24, 774 - 786.

Henderson, M. D., Harrison, W. H., 2008. Taphonomy and environment of deposition of a juvenile tyrannosaurid skeleton from the Hell Creek Formation (Latest Maastrichtian) of southeastern Montana. In: Larson, P., Carpenter, K. (Eds.), Tyrannosaurus Rex: The Tyrant King. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana, pp. 82 - 90.

Holtz, T. R., 2004. Tyrannosauroidea. In: Weishampel, D. B., Dodson, P., Osmolska, H. (Eds.), The Dinosauria. University of California Press, Los Angeles, California, pp. 111 - 136.

Ji, Q., Currie, P. J., Norell, M. A., Ji, S., 1998. Two feathered dinosaurs from northeastern China. Nature 393, 753 - 761.

Kobayashi, Y., Lu, J. - C., Dong, Z. - M., Barsbold, R., Azuma, Y., Tomida, Y., 1999. Herbivorous diet in an ornithomimid dinosaur. Nature 402, 480 - 481.

Larson, P., 2008. Variation and sexual dimorphism in Tyrannosaurus rex. In: Larson, P., Carpenter, K. (Eds.), Tyrannosaurus Rex: The Tyrant King. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana, pp. 102 - 128.

Larson, P., 2013 a. The case for Nanotyrannus. In: Parrish, J. M., Molnar, R. E., Currie, P. J., Koppelhus, E. B. (Eds.), Tyrannosaurid Paleobiology. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana, pp. 14 - 53.

Larson, P., 2013 b. The validity of Nanotyrannus lancensis (Theropoda, Lancian - Upper Maastrichtian of North America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 33, 159 A.

Lautenschalger, S., Witmer, L. M., Altangerel, P., Rayfield, E. J., 2013. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 110, 20657 - 20662.

Makovicky, P. J., Norell, M. A., 2004. Troodontidae. In: Weishampel, D. B., Dodson, P., Osmolska, H. (Eds.), The Dinosauria. University of California Press, Los Angeles, California, pp. 184 - 195.

Molnar, R. E., Farlow, J. O., 1990. Carnosaur paleobiology. In: Weishampel, D. B., Dodson, P., Osmolska, H. (Eds.), The Dinosauria. University of California Press, Los Angeles, California, pp. 210 - 224.

Norell, M. A., Clark, J. M., Demberelyin, D., Rhinchen, B., Chiappe, L. M., Davidson, A. R., McKenna, M. C., Altangerel, P., Novacek, M. J., 1994. A theropod dinosaur embryo and the affinities of the Flaming Cliffs dinosaur eggs. Science 266, 779 - 782.

Norell, M. A., Makovicky, P. J., Currie, P. J., 2001. The beaks of ostrich dinosaurs. Nature 12, 873 - 874.

Paul, G. S., 1988. Predatory Dinosaurs of the World: A Complete Illustrated Guide. Simon and Schuster, New York, New York, 464 pp.

Peterson, J. E., Henderson, M. D., Scherer, R. P., Vittore, C. P., 2009. Face biting on a juvenile tyrannosaurid and behavioral implications. PALAIOS 24, 780 - 784.

Pu, H., Kobayashi, Y., Lu, J., Xu, L., Wu, Y., Chang, H., Zhang, J., Jia, S., 2013. An unusual basal therizinosaur dinosaur with an ornithischian dental arrangement from northeastern China. PLoS One 5, e 63423.

Rayfield, E. J., Norman, D. B., Horner, C. C., Horner, J. R., Smith, P. M., Thomason, J. J., Upchurch, P., 2001. Cranial design and function in a large theropod dinosaur. Nature 409, 1033 - 1037.

Russell, D. A., 1970. Tyrannosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of western Canada. National Museum of Natural Science Publications in Palaeontology 1, 1 - 34.

Sampson, S. D., Witmer, L. M., 2007. Craniofacial anatomy of Majungasaurus crenatissimus (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir 8, 32 - 102.

Snively, E., Henderson, D. M., Phillips, D. S., 2006. Fused and vaulted nasals of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs: implications for cranial strength and feeding mechanics. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 51, 435 - 454.

Snively, E., Russell, A. P., 2007. Functional variation of neck muscles and their relation to feeding style in Tyrannosauridae and other large theropod dinosaurs. Anatomical Record 290, 934 - 957.

Therrien, F., Henderson, D. M., Ruff, C. B., 2005. Bite me; Biomechanical models of theropod mandibles and implications for feeding behavior. In: Carpenter, K. (Ed.), The Carnivorous Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana, pp. 179 - 237.

Van Valkenburgh, B., 1996. Feeding behavior in free-ranging, large African carnivores. Journal of Mammalogy 1, 240 - 254.

Varricchio, D. J., 2001. Gut contents from a Cretaceous tyrannosaurid: implications for theropod dinosaur digestive tracts. Journal of Paleontology 75, 401 - 406.

Xu, X., Cheng, Y., Wang, X., Chang, C., 2002. An unusual oviraptorosaurian dinosaur from China. Nature 419, 291 - 293.

Zanno, L. E., Gillette, D. D., Albright, L. B., Titus, A. L., 2009. A new North American therizinosaurid and the role of herbivory in ' predatory' dinosaur evolution. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 276, 3305 - 3511.

Fig. 1. Lateral views of theropod skulls demonstrating presence or absence of the dentary groove. The dentary groove is present in the primitive theropod (A) Coelophysis bauri (NMMNH P-42200), as well as in the derived theropod (B) Compsognathus longipes (BSP AS I 563). The dentary groove is present in the tyrannosaurids (C) Gorgosaurus libratus (TCM 2001.89.1) and (D) Nanotyrannus lancensis (“Jane”; BMR P2002.4.1). The dentary groove is absent in both (E1) young (LACM 28471) and (E2) adult (“Sue”; FMNH PR2081) Tyrannosaurus rex. Arrows indicate the position of the groove, when present. Scale bars equal 5 cm.

Fig. 2. Cladogram of Theropoda modifed from Carrano et al. (2012). Thickened branches indicate lineages possessing the dentary groove, thin branches indicate lineages in which the groove is absent. Grayed-out braches marked with dashed lines indicate taxa without a known dentary. Circled numbers indicate sequence of losses of the dentary groove assuming maximum parsimony.

Fig. 3. Proposed phylogenetic relationships of Nanotyrannus within Tyrannosauroidea with distribution of the theropod dentary groove on trees indicated with thickened bars. (A) Most parsimonious cladogram proposed by this study placing Nanotyrannus as sister to the Albertosaurinae.(B) Relationship sensu Currie (2003a) placing Nanotyrannus as sister to Tyrannosaurus. This tree requires 5 more independent losses of the dentary groove than the tree proposed in this study. (C) Relationship proposed by Brusatte et al. (2010) placing Nanotyrannus as a juvenile Tyrannosaurus. This tree requires 4 more independent losses than the tree proposed in this study and a loss of the dentary groove through ontogeny in Tyrannosaurus.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

1 (by jeremy, 2020-06-03 12:47:30)

2 (by jeremy, 2021-04-23 09:34:27)

3 (by ExternalLinkService, 2021-04-23 11:12:10)

4 (by felipe, 2021-08-16 00:02:43)

5 (by ExternalLinkService, 2021-09-22 15:29:11)

6 (by jeremy, 2022-02-03 13:23:31)

7 (by jeremy, 2022-02-22 11:17:17)

8 (by jeremy, 2022-02-22 11:53:38)

9 (by jeremy, 2022-04-12 10:26:33)

10 (by admin, 2023-10-16 01:13:17)

11 (by ExternalLinkService, 2023-10-16 01:23:26)