Cerithidea anticipata Iredale, 1929

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3775.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:D9FF6080-0316-4433-ABB8-7D6D6F2BF24B |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5694426 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03DA0723-6525-2865-D1A0-FF4DFB8C8C92 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Cerithidea anticipata Iredale, 1929 |

| status |

|

Cerithidea anticipata Iredale, 1929 View in CoL

( Figures 2 View FIGURE 2 C, 10, 11)

Cerithium obtusum var. b Lamarck, 1822 : 71

( MHNG INVE 51622 (formerly MHNG 1097/24 ), photograph seen;

not Cerithium obtusum Lamarck, 1822 ).

Cerithium obtusum — Kiener, 1841 –1842: 95–96, pl. 29, fig. 2 (in part, includes C. obtusa View in CoL ; not Lamarck, 1822).

Cerithidea obtusa View in CoL — Cernohorsky, 1972: 60, pl. 13, fig. 1 (in part, includes C. obtusa View in CoL ; not Lamarck, 1822). Healy, 1983: 57–75, figs 62, 95–98 (euspermatozoa; not Lamarck, 1822).

Cerithidea (Cerithidea) obtusa View in CoL — Wilson, 1993: 133, pl. 15, fig. 15 (not Lamarck, 1822).

Cerithium kienerii Hombron & Jacquinot, 1848 : pl. 23, figs 4, 5 (living animal)

(Rafles-Bay [Raffles Bay, Cobourg Peninsula, Northern Territory, Australia]; holotype MNHN 25692, Fig. 10A View FIGURE 10. A – P ; as C. kennerii ;

not Cantraine, 1835). Rousseau, 1854: 96 –97 (as kieneri ). Sowerby, 1855: 886, pl. 186, fig. 272 (as kieneri ). von Martens, 1897a: 188 (as kennerii ).

Cerithidea kieneri —H. Adams & A. Adams, 1854: 293. Sowerby, 1866: sp. 6, pl. 1, fig. 6. Hedley, 1909: 357. Allan, 1950: 87 – 88.

Potamides (Cerithidea) obtusa var. kieneri — Tryon, 1887: 161, pl. 32, fig. 53, pl. 33, fig. 61.

Cerithium (Cerithidea) kieneri — Kobelt, 1893: 159–160, pl. 30, fig. 1.

Cerithidea multicostata Schepman, 1919: 192 View in CoL , pl. 8, fig. 3, 3a

(Merauke, New Guinea [East Papua, Indonesia]; syntypes ZMA 136547).

Van der Bijl et al., 2010: 72, fig. 178.

Cerithidea anticipata Iredale, 1929: 278 View in CoL (new name for Cerithium kieneri Hombron & Jacquinot, 1848 , not Cantraine, 1835). Houbrick, 1986: 284, 285, figs 5, 6, fig. 15 (radula). Cecalupo, 2005: 316, pl. 31, fig. 21. Cecalupo, 2006: 27, 176, pl. 57, fig. 13a–c (in part, includes C. balteata View in CoL , Cerithideopsilla conica , Cerithideopsis largillierti View in CoL ). Reid et al., 2008: 680 –699, figs 1, 2 (phylogeny). Jarrett, 2011: 40, fig. 95. Willan, 2013: 77, fig. 8. Reid et al., 2013: figs 1 (shell, phylogeny), 2 (map).

Cerithidea (Cerithidea) anticipata View in CoL — Wilson, 1993: 132 –133, pl. 15, fig. 16.

Cerithidea reidi View in CoL — Cecalupo, 2006: 85, 210, 233–234 (not Houbrick, 1986; in part, includes C. reidi View in CoL , C. dohrni View in CoL ).

Taxonomic history. This species was first noticed as ‘var. b’ of Cerithium obtusum by Lamarck (1822; see Taxonomic History of that species) and subsequently figured under the same name by Kiener (1841 –1842). This was presumably the reason why Hombron & Jacquinot (1848) named the species Cerithium kienerii , which they distinguished from Cerithium obtusum by the different body coloration. Nevertheless, the name C. obtusa has occasionally been used for this Australasian species in more recent literature ( Cernohorsky 1972; Healy, 1983; Wilson 1993).

The authorship and spelling of Cerithium kienerii require justification. As demonstrated by Clark & Crosnier (2000), the Atlas of the Voyage au Pole Sud et dans l’Océanie sur les corvettes l’Astrolabe et la Zélée was published in parts (pl. 23 in 1848) by Hombron & Jacquinot, sometimes before the accompanying text. The written descriptions of molluscs were provided by Rousseau and published in 1854. According to the ICZN Code (1999: Art.12.2.7) an illustration with a binominal name constitutes a valid indication, so in this case the new names in the Atlas are available and take priority over those in the text. In its original form in the caption to plate 23 the specific name was spelled kennerii , but this appeared as kieneri in Rousseau’s text. This is taken as evidence of an incorrect original spelling (ICZN 1999: Art. 32.5.1), even though the correction was made in a subsequent volume of the original work, since the subsequent text was prepared under the supervision of the original authors. The original genitive ending –ii is not to be changed, however (ICZN 1999: Art. 33.4). An alternative interpretation is that the correction to kieneri was an incorrect subsequent spelling that cannot be used as a substitute name (ICZN 1999: Art. 33.3); this would have the undesirable consequence that kennerii would become the valid name for this species. The original form of the name, kennerii , has in fact been used only once, by von Martens (1897a). Several early authors (H. Adams & A. Adams 1854; Sowerby 1855, 1866; Tryon 1887) evidently recognized that kennerii was an error, and attributed the corrected version kieneri to Hombron & Jacquinot, and this adds to the argument that the latter (but with the – ii ending) is the correct original spelling (ICZN 1999: Art. 33.3.1). During the twentieth century the corrected name was used at least twice, by Hedley (1909) and Allan (1950).

At present this species is familiar as C. anticipata , a replacement name provided by Iredale (1929) for the preoccupied Cerithium kienerii . In fact this replacement may not have been necessary, because an older available name exists: C. multicostata Schepman, 1919 . This was based on the form with numerous axial ribs from southern New Guinea. Comparison of shells suggests that this form is conspecific with those from Australia, but genetic distances within Australia indicate that more than one species could exist within a complex (see Remarks). Until this is clarified by new data, it seems premature to change the familiar name C. anticipata .

Diagnosis. Shell: periphery rounded or weakly angled; aperture flared, anterior canal and apertural projection well developed; 14–40 axial ribs on penultimate whorl; ventrolateral varix a slightly enlarged rib at 200–260°; 5 spiral cords on spire, 4–10 above periphery on last whorl; brown with darker spiral cords. Northern Australia and New Guinea. COI GenBank AM932760 View Materials – AM932762 View Materials .

Material examined. 57 lots.

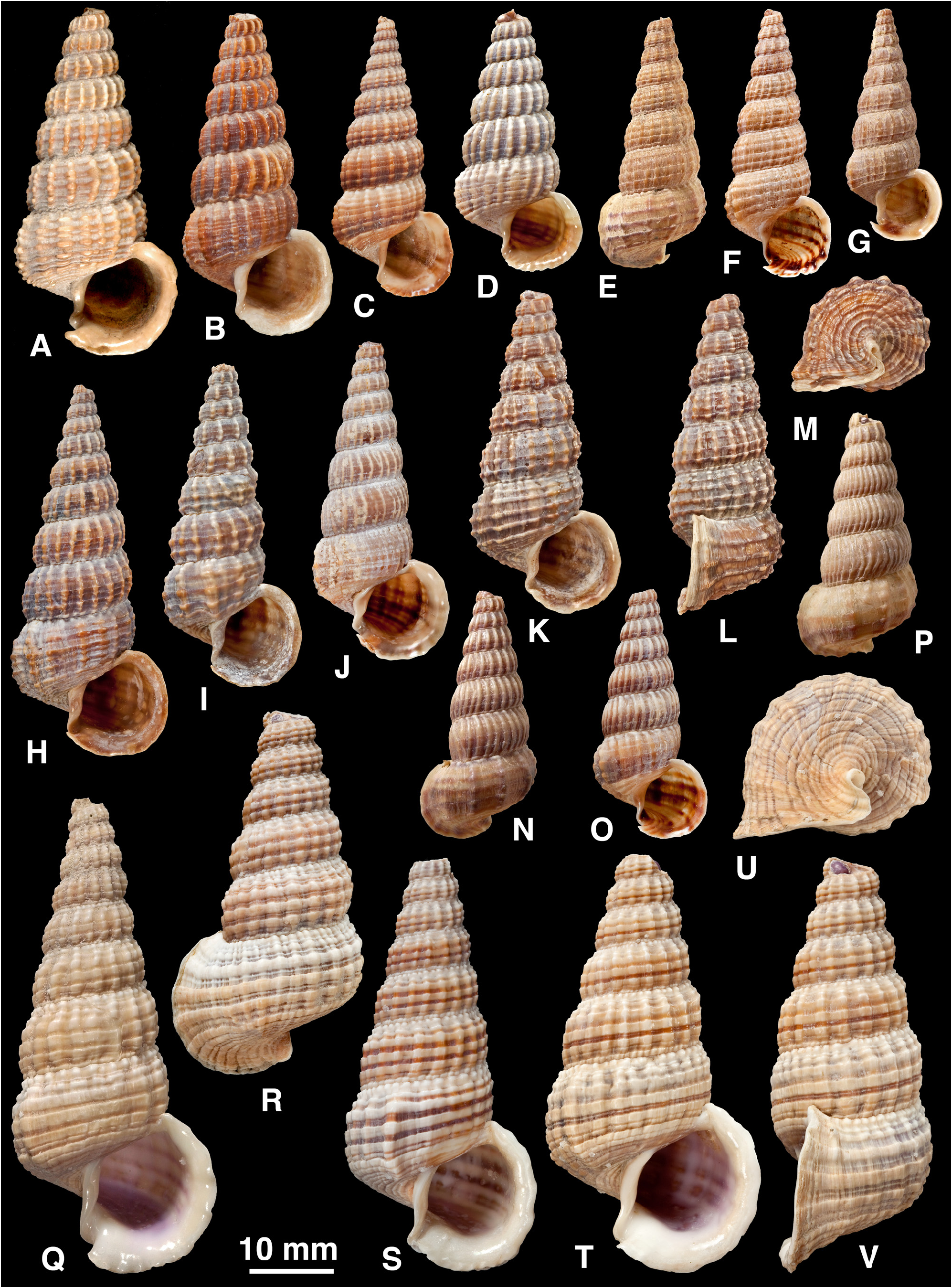

Shell ( Fig. 10A–P View FIGURE 10. A – P ): H = 24.0– 50.3 mm. Shape elongated conical (H/B = 2.01–2.62, SH = 2.83–3.54); decollate, 7–10 whorls remaining; spire whorls rounded, suture distinct; spire profile straight to slightly convex; periphery rounded or weakly angled; moderately solid. Adult lip flared, moderately thickened; apertural margin planar in side view; strong anterior projection adjacent to deep notch of anterior canal. Sculpture on spire of straight to slightly curved (opisthocyrt) axial ribs, often bifurcating posteriorly (adapically) to give a row of granules at suture (occasionally bifurcation occurs lower on whorl to increase number of axial ribs; Fig. 10J, N–P View FIGURE 10. A – P ); ribs prominent, narrowly rounded, interspaces 1.5–2 times width of ribs (occasionally equal), 14–40 ribs on penultimate whorl, remaining strong but becoming more distant after ventrolateral varix, weak on base; spire whorls with 5 narrow spiral cords, often forming nodules where they cross axial ribs, usually increasing by interpolation of narrower threads to give 4–10 spiral cords and threads above periphery on final whorl; base with 7–11 narrow ridges, peripheral one is a cord of same size as primary cords above, but others on base slightly narrower. Ventrolateral varix a slightly enlarged rib at 200–260°. Surface with fine spiral microstriae on periostracum. Colour: pinkish brown to fawn, spiral ribs usually darker brown (especially on anterior half of whorls, giving appearance of broad brown band), axial ribs paler; aperture pale brown, spiral lines showing through.

Animal ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 C): Head and base of tentacles pinkish grey with cream spots; anterior half of snout blackish with scattered yellow spots; tentacles cream, grey towards tip; sides of foot dark grey speckled with grey, brown and white, small yellow spots at margin; sole of foot grey with pinkish border; mantle blue grey.

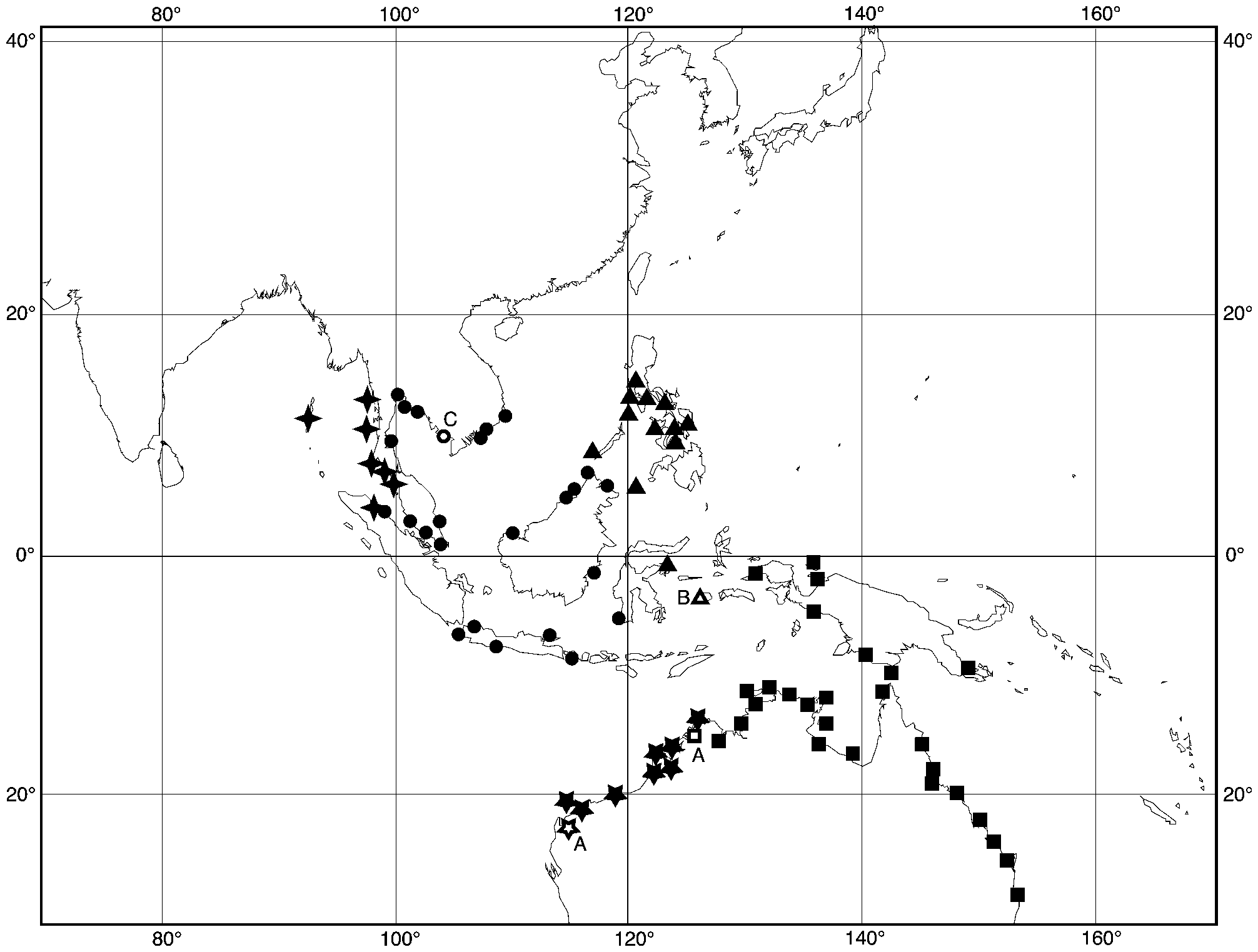

Range ( Fig. 11 View FIGURE 11 ): Queensland (Qld) and Northern Territory (NT) of Australia, New Guinea. Records: Australia: Prince Regent River Reserve, Western Australia ( Houbrick 1986: fig. 5); Forrest River Mission, 50 miles from Wyndham, NT (AM C.085156); Buffalo Creek, Darwin, NT ( NHMUK 20130241; USNM 828819); Bing Bong Station, W Gulf of Carpentaria, NT (AM C.412929); Allen I., S Wellesley Is, S Gulf of Carpentaria, Qld (AM C.015839); Moa I., Torres Strait, Qld ( NHMUK 20130244) ; Cockle Bay, Magnetic I., Qld ( NHMUK; USNM 828828); Lota Creek, Wynnum, Moreton Bay, Qld (AM C.138069); Brunswick R., New South Wales (D. Riek, pers. comm.). Indonesia: Kupang, West Timor ( ZMB); Biak, Soepiori I., Schouten Is, East Papua ( ANSP 207534) ; Sulawati I., East Papua (AM); Kokenau, Mimika R., East Papua (AM C.458258); Merauke, East Papua (AM C. 121289). Papua New Guinea: Collingwood Bay (AM C.18891).

Sowerby (1855, 1866) erroneously gave the locality as ‘ Philippines and Borneo’ (as Cerithium kieneri ).

Habitat and ecology. This species is typically found in the Ceriops zone of mangrove forests, often among shrubs on the fringes of bare salt pans, at heights of up to 1 m on trunks, and sometimes on firm mud beneath the trees. It is less common on trunks in the Rhizophora and Bruguiera zones, or in the landward fringe, where it may reach 3 m up the trees.

In a detailed study at Darwin, McGuiness (1994) found C. anticipata to be most abundant in the mangrove zone dominated by Ceriops , often in and around clearings with dead trees (caused by cyclone damage). The animals rested in shady sites on trees, attached by dried mucus with only a small part of the outer lip in contact with the trunk; they climbed higher, and were less active, during neap tides that did not flood the forest than during spring tides. Snails that were tethered to prevent climbing died, apparently from physiological stress (but these were tethered during neap tides in an open clearing where soil temperature reached 45°C, so these results may not be typical). It was suggested that, consequently, the major reason for the climbing behaviour was avoidance of physiological stress, not escape from subtidal predators that enter the mangrove during spring tides. Nevertheless, predation was evident, because many snails showed signs of shell damage. Studies of C. decollata have suggested that predator avoidance has led to the evolution of climbing behaviour ( Cockcroft & Forbes 1981a; Vannini et al. 2006). McGuiness (1994) argued that the Darwin site was at a higher tidal level than the locations of studies of C. decollata , so that physiological stress was more significant.

In the vicinity of Darwin, Willan (2013: 77) reported that C. anticipata can be found in both mangrove and salt marsh environments, and occurs in “extremely high densities” among the foliage of the canopy, where it is quiescent during the drier months. He noted that it is rarely found on the ground, mainly foraging at low levels on the trunks of various mangrove tree species, when conditions are moist. However, McGuiness (1994) implied that activity takes place mainly at night, so daytime observations may not be representative.

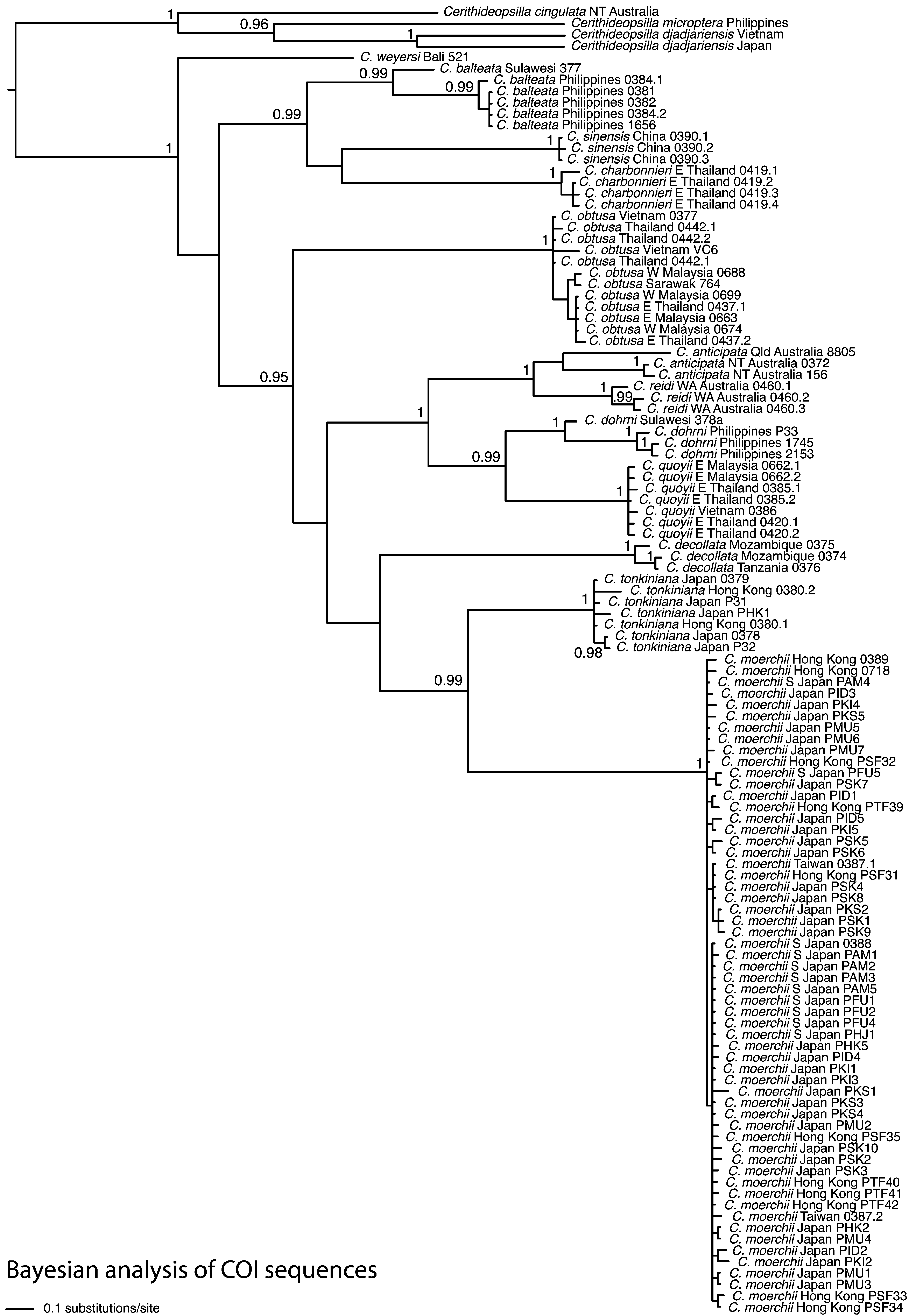

Remarks. The shell shows considerable regional variation. Specimens from Merauke, S New Guinea, and one from the nearby Torres Strait ( Fig. 10J, N–P View FIGURE 10. A – P ) show increased numbers of fine axial ribs on the spire (these were named C. multicostata Schepman, 1919 ). Shells from elsewhere in New Guinea are slender and delicate, but again have fine and sometimes numerous axial ribs ( Fig. 10E, F View FIGURE 10. A – P ). Shells from E Queensland are large, with coarse sculpture ( Fig. 10 H, I, K–M View FIGURE 10. A – P ). Those from the Gulf of Carpentaria are thick and pale. In the Northern Territory the whorls are slightly compressed vertically to produce a broader shell ( Fig. 10A–D View FIGURE 10. A – P ). COI sequence data reveal a deep division between two specimens from Darwin and one from the Torres Strait (uncorrected pairwise distance = 0.072) and phylogenetic analysis does not give significant support to the monophyly of all three ( Reid et al. 2013; Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 ). However, molecular sampling is so far too limited to determine whether this division corresponds in any way with the observed pattern of morphological variation. The distribution appears to be continuous around the northern coast of Australia, so does not suggest any geographical separation between eastern and western populations. Nevertheless, a pattern of eastern and western genetic differentiation (both intra- and inter-specific) across northern Australia is common in marine organisms and has been explained by isolation during glacial low sea-level stands ( Reid et al. 2006, 2010). Further investigation is required of genetic structure and possible speciation in C. anticipata .

The sister species of C. anticipata is C. reidi ( Reid et al. 2013; Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 ). Morphologically, C. anticipata is distinguished from C. reidi by smaller size, darker coloration and narrower ribs and cords (see Remarks on C. reidi ). However, the genetic distance between them is similar to that between the divergent sequences of C. anticipata (uncorrected pairwise distance for COI = 0.076, cf 0.072 within C. anticipata ). Together, all form a wellsupported clade ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 ). Houbrick (1986) reported that the ranges of these two species just overlap in Admiralty Gulf in northern Western Australia. He noted that, in the region of overlap, specimens of C. anticipata “are larger than specimens from northern Australia and Queensland and are more similar to C. reidi in shell sculpture. These larger C. anticipata , while resembling C. reidi , never have a purple aperture and do not attain the large size of C. reidi . These two species are probably very closely related, as their radulae and shell sculptures are morphologically similar even though there is great size disparity” ( Houbrick 1986: 285). He illustrated a shell that appears to be C. anticipata , from Prince Regent River ( Houbrick 1986: fig. 5), which is just within the geographical range of C. reidi . Nevertheless, it is possible that some of the shells of ‘ C. anticipata ’ he observed from Admiralty Gulf were actually small specimens of C. reidi (see Remarks on C. reidi ) and their respective ranges in this area remain to be confirmed. Detailed genetic study is required to test whether these are distinct species, or whether hybridization occurs, leading to intergradation where they overlap.

In eastern New Guinea the range of C. anticipata overlaps that of C. balteata and shells of these two species can be very similar. Cerithidea anticipata can be distinguished by its stronger spiral sculpture on the spire whorls ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 Q–U, cf. Fig. 10E–G View FIGURE 10. A – P ; see Remarks on C. balteata ).

Aboriginal people in Australia do not use C. anticipata as food ( Willan 2013).

| MHNG |

Museum d'Histoire Naturelle |

| MNHN |

Museum National d'Histoire Naturelle |

| ZMA |

Universiteit van Amsterdam, Zoologisch Museum |

| NHMUK |

Natural History Museum, London |

| USNM |

Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History |

| ZMB |

Museum für Naturkunde Berlin (Zoological Collections) |

| ANSP |

Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Cerithidea anticipata Iredale, 1929

| Reid, David G. 2014 |

| Bijl 2010: 72 |

Cerithidea reidi

| Cecalupo 2006: 85 |

Cerithidea (Cerithidea) obtusa

| Wilson 1993: 133 |

Cerithidea (Cerithidea) anticipata

| Wilson 1993: 132 |

Cerithidea obtusa

| Healy 1983: 57-75 |

| Cernohorsky 1972: 60 |

Cerithidea anticipata

| Willan 2013: 77 |

| Jarrett 2011: 40 |

| Reid 2008: 680 |

| Cecalupo 2006: 27 |

| Cecalupo 2005: 316 |

| Houbrick 1986: 284 |

| Iredale 1929: 278 |

Cerithidea multicostata

| Schepman 1919: 192 |

Cerithidea kieneri

| Allan 1950: 87 |

| Hedley 1909: 357 |

Cerithium (Cerithidea) kieneri

| Kobelt 1893: 159-160 |

Potamides (Cerithidea) obtusa var. kieneri

| Tryon 1887: 161 |

kieneri

| Martens 1897: 188 |

| Sowerby 1855: 886 |

| Rousseau 1854: 96 |

Cerithium obtusum

| Kiener 1841: 95-96 |

Cerithium obtusum var. b Lamarck, 1822

| Lamarck 1822: 71 |