Drymoluber brazili (Gomes, 1918)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3716.3.3 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:71B98313-E0FC-427D-A06F-6917B64A64F8 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6154465 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03C9885D-8F21-FFD7-FF25-F9964A1B25E9 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Drymoluber brazili (Gomes, 1918) |

| status |

|

Drymoluber brazili (Gomes, 1918)

Drymobius brazili Gomes, 1918 . Memórias do Instituto Butantan, 1, p. 81. Holotype: IBSP 696 (probably destroyed during the fire of May 2010).

Drymobius rubriceps Amaral, 1923 . Proceedings of the New England Zoological Club, 8, p. 85. Holotype: IBSP 1844 (probably destroyed during the fire of May 2010).

Drymobius boddaerti (partim.)—Amaral 1929. Memórias do Instituto Butantan, 4, p. 11.

Drymoluber brazili— Stuart 1932. Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, 236, p. 4.

The types of Drymoluber brazili and its junior synonym, Drymobius rubriceps , were personally examined by the senior author in 2009. On May 2010, the collections of Instituto Butantan in São Paulo, Brazil, where those and most known specimens of D. brazili were maintained were consumed in a fire (Warrell et al. 2010; Franco 2012). It is estimated that 80% of the snake collection was destroyed, but there is still no information if the types of Drymoluber brazili were lost (F. Franco, pers. comm.).

Holotype: Instituto Butantan, São Paulo, IBSP 696, adult male, SVL 1090 mm, TL 473 mm, collected on September 1914 in the Estação Ferroviária de Engenheiro Lisboa (currently inactive), near the municipality of Uberaba (-19.80, -47.60), Minas Gerais, Brazil. Specimen personally examined by the senior author.

Paratypes: Instituto Butantan, São Paulo, IBSP 383, adult male, SVL 863 mm, TL 394 mm, collected in February 1913, in the Estação Ferroviária Santa Eudóxia (currently inactive), municipality of São Carlos (-21.77, -47.78), São Paulo, Brazil; IBSP 573, adult female, SVL 854 mm, TL 422 mm, collected in February 1914, in the Estação Ferroviária de Sampaio Vidal (currently inactive), municipality of Ribeirão Bonito (-22.07, -48.18), São Paulo, Brazil; IBSP 574, adult male, SVL 862 mm, TL 268+N mm (broken tail), without locality data; IBSP 741, adult male, SVL 1120 mm, TL 162+N mm (broken tail), collected in December 1914, in the Estação Ferroviária Java (currently inactive), municipality of Boa Esperança do Sul (-21.99, -48.39), São Paulo, Brazil; IBSP 1286, adult female, SVL 898 mm, TL 402 mm, collected in May 1917, in the Estação Ferroviária Pedregulho (currently inactive), municipality of Pedregulho (-20.26, -47.48), São Paulo, Brazil. All specimens personally examined by the senior author.

About the type locality: In the 20th century the Instituto Butantan often received snakes from several Brazilian localities, sent by collectors to the institute via the railroads that crossed some regions of the country at that time. Thus, the accuracy of localities of specimens from railroads (like the type series of D. brazili ) must be treated with caution (Pereira et al. 2007). In the specific case of D. brazili , the Estação Ferroviária Engenheiro Lisboa (type locality), was located at km 555 of the Tronco-Catalão railroad, which, at the time of the collection of the holotype (September 1914) went from Campinas, São Paulo (-22.09, -47.05) to Ipameri, Goiás (-17.72, -48.15) (Giesbrecht 2009; Cavalcanti 2010). Although it is hard to identify the exact locality where the holotype of D. brazili was collected, we believe it really was in the proximities of the Tronco-Catalão railroad, since the road is located in areas with other confirmed records of the species (see map in Fig. 12 View FIGURE 12 ).

Similar locality problems exist with the paratypes that purportedly also are from rail stations. The Santa Eudóxia, Sampaio Vidal and Java stations, were part of a wide railroad network belonging to the Companhia Paulista de Estradas de Ferro that crossed the state of São Paulo from the southeast to the north and northwest (Giesbrecht 2009; Cavalcanti 2010). On the other hand, the Estação Ferroviária Pedregulho was located at km 455 on the Tronco-Catalão railroad.

Diagnosis: Drymoluber brazili can be distinguished from D. apurimacensis and D. dichrous by the following combination of characters: a) 17-17-15 dorsal scale rows with two apical pits; b) 182–200 ventrals in males, 185– 202 in females; c) 109–127 subcaudals in males, 109–126 in females; d) 19–25 maxillary teeth. See Table 5.

Comparisons: Drymoluber apurimacensis has 13-13-13 dorsal scales rows, and D. dichrous has 15-15-15. Apical pits are absent in D. apurimacensis . Drymoluber apurimacensis has 158–164 ventrals in males and 166–182 in females, 84–93 subcaudals in males and 87–91 in females. Drymoluber dichrous has 157–173 ventrals in males and 160–180 in females, 87–110 subcaudals in males and 86–109 in females. Drymoluber apurimacensis has 14– 16 maxillary teeth.

Small specimens of Drymoluber brazili have dark crossbands 2–6 scales wide (mean 3.6) and light interspaces 0.5–5 scales wide (mean 1.6), while in a single specimen of D. apurimacensis the dark crossbands are 1–2 scales wide and the light interspaces 2–3 scales wide. Young specimens of D. dichrous have dark crossbands with similar width to those of D. brazili (1.5–7 scales, mean 3.6), but the pale interspaces are on average narrower (0.5–2.5 scales, mean 0.8).

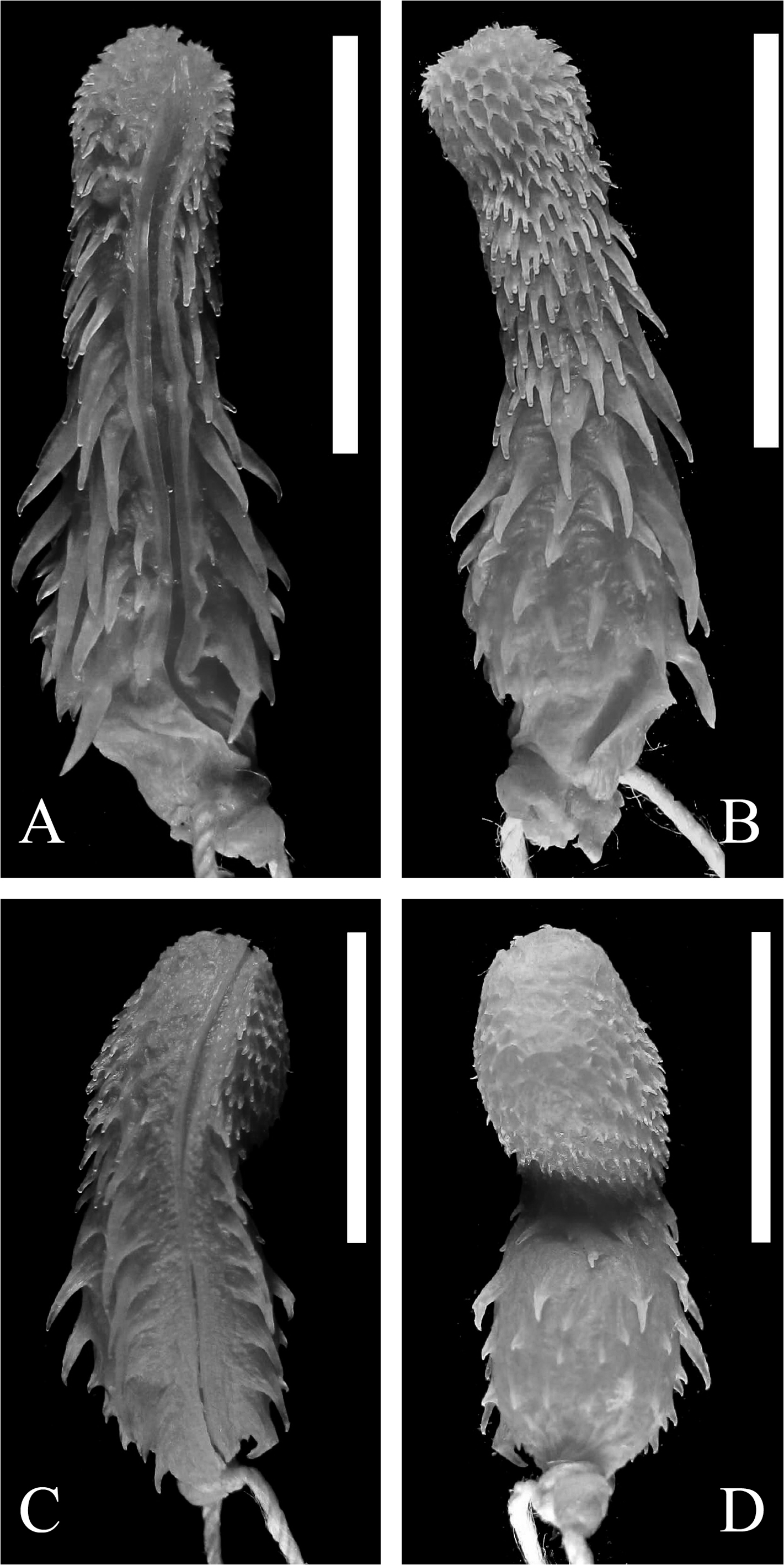

The hemipenes of Drymoluber brazili tend to have fewer calyces than that of D. dichrous and D. apurimacensis , larger spinulate flounces, and spines in the lobular region. The walls of the sulcus spermaticus are less ornamented. The spines of the asulcate face in general are smaller than those of D. dichrous and D. apurimacensis , especially those most proximal.

Redescription of the holotype ( Fig. 18 View FIGURE 18 ): Snout-vent length 1090 mm and tail length 473 mm; head distinct from the body, 35.1 mm long (3.2% of the SVL); greatest width of head 15.20 mm (43% of head length); width of head at the supraoculars 11.3 mm; internasal distance 6.1 mm; eye diameter 6.0 mm; eye-nostril distance 5.9 mm. Smooth dorsal scales in 17-17-15 rows with two apical pits; 190 ventrals and 1 preventral (sensu Peters 1964); cloacal shield entire; tail intact with 117 divided subcaudals and one terminal spine; rostral wider than high, visible from above; internasals and prefrontals slightly wider than long; each prefrontal contacting the frontal, supraocular, internasals, posterior nasal, preocular and loreal; frontal about 1.5 times longer than wide; supraoculars longer than wide; parietals about 1.5 times longer than wide; nasal divided above and below the naris, mainly in contact with the first supralabial, but also with the second; loreal slightly longer than high, (vaguely resembling a parallelogram), contacting the second and third supralabials; one preocular; two postoculars, the upper one larger than the lower; two anterior temporals (one upper and one lower) and two posterior temporals (one upper and one lower) (1/1+1/1) on both sides of the head; eight supralabials, the fourth and the fifth contacting the eye; mental triangular, wider than long; nine infralabials, the first pair in contact behind the mental; first to fifth infralabials in contact with the first pair of chinshields; fifth infralabial in contact with the second pair of chinshields; fifth to ninth infralabials contacting the gulars; first pair of chinshields about the half the length of the second; 23 maxillary teeth, increasing in size posteriorly.

There are some small differences between the redescription of the holotype presented here (inside brackets) and the original description. Gomes (1918) decribed the holotype as having 22 maxillary teeth, internasals as wide as long, 10 infralabials, 191 ventrals, SVL 1110 mm and TL = 480 mm. The difference in the number of infralabials may be explained on the basis of the method used in both studies. In the present work, the posterior boundary of the infralabial row is defined as the last scale completely covered by the last supralabial (Peters 1964) ( Fig. 18 View FIGURE 18 C), which is not the definition seemingly used by Gomes (1918). The differences in SVL and TL may be due to a small error in the original measuring, or a reduction in size caused by fixation and preservation over time time (Vervust et al. 2009; Guimarães et al. 2010). This situation is also applicable to the paratypes of D. brazili .

Coloration of the holotype: Gomes (1918) described the holotype in life as having olive-green color in the head and on the anterior part of the body, becoming reddish-brown in the posterior part of body and on the tail. The venter was yellowish-white, while the lateral edges of the ventral plates were the same color as the dorsum. When the senior author examined the holotype, it was grayish-brown on the dorsum of head and anterior half of the body, becoming yellowish-brown on the posterior half of the body and tail. Supralabials, gular region and venter were yellowish-brown and similar to or slightly paler than the dorsum.

Coloration of preserved adults: The dorsal coloration of most of the examined adults (n=49; 77.8%) is uniform bluish-gray, bluish-brown or yellowish-brown throughout. A few specimens (n=13; 20.6%) are grayishbrown or bluish-brown on the anterior half of the body and yellowish-brown on the posterior half. One specimen has faint crossbands as are present in the juvenile color pattern.

The venter of most specimens (n=49; 77.8%) is immaculate, yellowish-cream, and the lateral edges of ventrals have the same color as the dorsal scales. In one specimen (1.6%) the dorsal coloration extends into the ventral region; in other specimens (n=13; 20.6%) the venter is yellowish-colored with some dark spots, and the lateral edges of ventrals are the same color as the dorsal scales.

Dorsally, the tail is the same color as the body, but shows some variations in the subcaudal coloration. In 24 specimens (38.1%) the subcaudals are yellowish-cream, immaculate, and with their lateral edges the same color as the dorsum. In some snakes, the lateral edges are inconspicuous and the same color as subcaudals (n=5; 7.9%). In a few, the subcaudals have more than half their area dark like the dorsals (n=1; 1.6%), or have black spots throughout their area (n=1; 1.6%). In others, black spots are numerous only in the posterior region of the tail (n=24; 38.1%), or the posterior part of tail is completely black (n=8; 12.7%).

In all specimens the head is uniform dorsally and the same color as the dorsum of body. The gular region is immaculate, yellowish-cream. The supralabials of most adult specimens have dark lateral edges (mainly in the last scales (n=59; 93.6%), but in some specimens visible markings are absent (n=4; 6.4%).

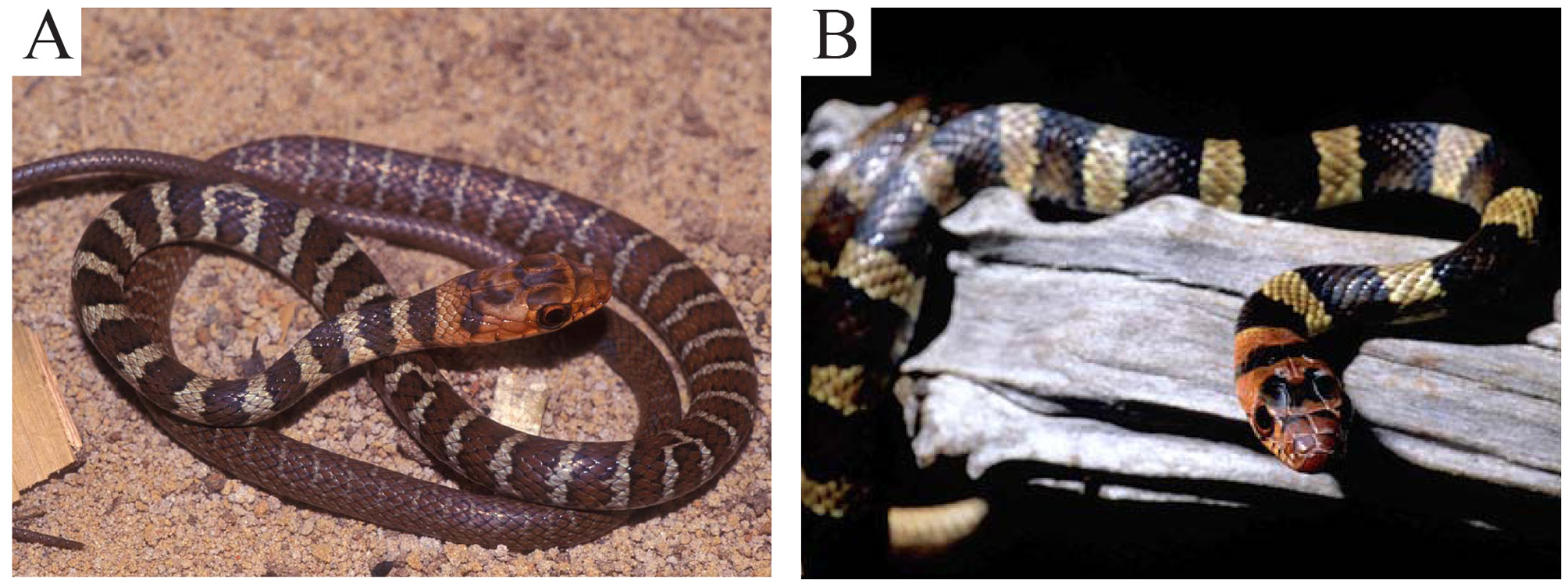

Coloration of adults in life: Unlike Drymoluber dichrous , there is little information about the coloration of D. brazili in life. Gomes (1918) described the the type series in life as follows: two specimens have the dorsum completely olive-green, while in the other three, and the holotype, the posterior part of the dorsum is reddishbrown. This same pattern is seen in the illustration ( Fig. 19 View FIGURE 19 A) of one specimen from Visconde de Parnaíba, São Paulo (IBSP 4812) published by Amaral (1978). In some specimens, the dorsal color may consist of grayish tones ( Fig. 19 View FIGURE 19 B).

Coloration of preserved juveniles: The color pattern of preserved juveniles of Drymoluber brazili is similar to that of the other species of the genus, consisting of dark crossbands separated by pale interspaces. Only two specimens (10%) have crossbands (47 and 54) visible throughout the body (MZUSP 9596 and IBSP 29221). Crossbands on the tail were not visible in any specimen. The dark crossbands varied in width between 2–6 vertebral/paravertebral scales (mean 3.6; SD=0.89; n=62 crossbands). The last crossband anterior to the cloaca is the narrowest and two scales wide (n=2; 10%), while the first crossband on the body is the widest, 2–6 scales wide (mean 4; SD=0.95; n=20; 100%). The widths of the pale interspaces vary between 0.5–5 scales (mean 1.6; SD=0.97; n=62 interespaces). The interspace anterior to the fifth crossband anterior to the cloaca is the narrowest, with 0.5 or 1.5 scales (n=2; 10%). The interspace posterior to the first crossband is the widest, with 1–5 scales (mean 2.32; SD=0.90; n=20; 100%).

The venter of young specimens is always yellowish-cream and immaculate, and the lateral edges of ventral plates are the same color as the dorsals.

The subcaudals are cream colored, with the lateral edges darkened (n=9; 45%), cream (n=6; 30%), or cream with only the posterior edges darkened (n=5; 25%).

The head has light internasals, light pre-frontals with darkened posterior edges, and a dark frontal and supraoculars with light anterior edges. A light stripe in the parietal region can be present and immaculate (n=9; 45%) or maculate (n=4; 20%). In the remaining specimens (n=7; 35%) the parietals are dark ( Fig. 11 View FIGURE 11 ). As occurs in other species of the genus, lighter shades on the head darken as the specimens grow.

As in adults, the gular region of the juveniles is pale and immaculate. The supralabials have faint dark markings on their lateral edges.

Coloration of juveniles in life: In life, the light colored regions in preserved juveniles are shades of white, cream and light-brown, except in the head and neck, where an orange-red color prevails. The dark colored regions (including crossbands) vary in shades of brown, olive-green and dark-gray ( Fig. 20 View FIGURE 20 ; Amaral 1923).

Apparently, only D. brazili juveniles have this reddish coloration on the head. However, since those colors tend to become white in preserved specimens, and because photographs and information about the coloration of live juveniles of Drymoluber are uncommon, it is difficult to know whether this character is diagnostic for D. brazili .

Hemipenial morphology (n=6) ( Fig. 21 View FIGURE 21 ): Hemipenis single, subcylindrical, not capitate. Sulcus spermaticus single and centrolinear. Lobe about half of the hemipenis length, with papillate calyces (5–10 papillae per calyx, most calyces deep) and spines bordering the sulcus spermaticus. The calyces are gradually replaced by spinulate flounces and spines proximally. The hemipenial body is covered by spines arranged in more or less transverse rows (about 60 or a few more spines in total). Walls of the sulcus spermaticus weakly ornamented, usually with few papillae and spinules. These walls are also bordered on both sides by a longitudinal row of 8–13 spines (mean 8; SD=1.97). The spines from the right side tend to increase in size toward the proximal region, while the spines from the left side increase in size up to the middle of the row, then decrease in size toward the proximal region (n=4). In the rest of the examined specimens (n=2), spines from both sides increase toward the proximal region of the hemipenis. A basal hook is present at the end of each row of spines bordering the sulcus, with the left hook more proximally than the right hook. None (n=2), or three to four small spines (n=2) or spinules (n=2) may be present between the left hook and the wall of the sulcus spermaticus.

One (n=2) or two (n=2) lateral spines, larger than the hooks, may be present to the left of the sulcus spermaticus, or two large lateral spines may be present on both sides of the sulcus (n=1). The asulcate face is formed by spines arranged in 6–7 more or less transverse rows (counted from proximal to distal region), with largest spines in the median rows, and proximal spines smaller than distal spines. In two specimens (MCNR 1736 and UFMT 6970), those spines are very small. The base of the hemipenis is smooth, with some grooves and several sparse spinules

Variation: Largest male with SVL 1178 mm, TL 410+N mm (IBSP 34369); largest female with SVL 1035 mm, TL 400+N mm (IBSP 17019). Twenty eight (28) specimens examined (33.7%) had broken tail. The tail of 24 of those specimens (28.9% of the total examined) was healed, suggesting the presence of pseudoautotomy in this species. Tail length of specimens with complete tail is 38.1–62.7% of the SVL in males (mean 44.2%; SD=4.23; n=29) and 41.11–56% (mean 45.7%; SD=3.5; n=26) in females. For variation in meristic characters, see Table 5.

Geographic distribution: Drymoluber brazili is distributed mainly in Brazil, with a single record from Paraguay (Canindeyú province). The species inhabits the Cerrado domain, with additional records from the Caatinga, Atlantic Forest and its transitional areas with the Cerrado ( Fig. 12 View FIGURE 12 ; Appendices II and III). França et al. (2006) reported the species in Vilhena, Rondônia, Brazil (-12.74, -60.15), in Amazonian savannas. However, that specimen (CHUNB 12791) is actually a D. dichrous . There is a record from Aripuanã, Mato Grosso, Brazil (- 10.15, -59.45) in the MPEG collection, but the specimen (MPEG 10419) could not be found, and we do not consider this record further. Therefore, the presence of D. brazili in the Amazonian region is unconfirmed.

In their material examined section, Lehr et al. (2004) listed three specimens of Drymoluber brazili deposited in MZUSP that were misidentified: MZUSP 5329 (from Morro Branco, Ceará, Brazil) actually is a young Drymarchon corais ; MZUSP 11263 (from Gaúcha do Norte, Mato Grosso, Brazil) and MZUSP 11442 (from Vila Rica, Mato Grosso, Brazil) are specimens of the genus Mastigodryas .

The records of Drymoluber brazili from the Atlantic Forest, in the municipalities of Colatina (-19.54, -40.64) and Baixo Guandú (-19.52, -41.02) state of Espírito Santo, and in Aimorés (-19.50, -41.06), state of Minas Gerais, suggest relictual populations. The lower Doce River region is relatively arid with notable occurrences of rocky outcrops that resemble Caatinga areas, different from the Atlantic Forest of the nearest regions (Jackson 1978; Ribon 1995). Modelings of the Atlantic Forest range under past climatic scenarios of 6000 and 21,000 years ago suggest that much of the area south of the Doce River was not predicted to retain a large, stable forest refuge, leading to an eastward expansion of the Cerrado (Carnaval & Moritz 2008). Thus, it is possible that in one of these times and benefited by the increasing of non-forested areas in southeastern Brazil, D. brazili expanded its distribution range.

Natural history: Drymoluber brazili inhabits open areas (Rodrigues 1996; França & Araújo 2006; França et al. 2008), and seems to be absent from altered habitats ( França & Araújo 2006). Moreira et al. (2009) recorded the species inhabiting termite mounds, a common behavior in Cerrado snakes. Drymoluber brazili has diurnal activity, and is probably terrestrial ( França & Araújo 2006; França et al. 2008). Gomes (1918), however, observed one of the specimens from the type series climbing in arboreal structures in captivity. Amaral (1978) and Pavan & Dixo (2004) cited D. brazili as arboriculous, but they did not state whether their data were obtained from previous published references or represent field observations.

There is a report of an unidentified Gymnophthalmidae as prey of Drymoluber brazili ( França et al. 2008). Additionally, Pavan & Dixo (2004) cited anurans as the main prey of this snake, probably based on uncited literature references, since they collected only one specimen of D. brazili .

França & Araújo (2006) recorded less than five eggs per clutch of Drymoluber brazili . One specimen examined in the present study (MZUFV 780) has four eggs.

Gomes (1918) recorded some observations of the defensive behavior of Drymoluber brazili : “When handled, the specimens I had examined did not try to bite; however, when bothered by repeated light hits on the dorsum, they assumed a strike posture similar to D. bifossatus and other species of close related genera ( Coluber , Spilotes , Herpetodryas ), also rapidly shaking the tail.” (translation by the authors). Brodie III & Brodie Jr. (2004) suggested that young cross-banded specimens might mimic coralsnakes ( Elapidae ).

The long tail of Drymoluber brazili (mean 44.2% of the SVL in males and 45.7% in females), with a tail beakage ratio of 28.9% (considering only those specimens where the breakage certainly occurred before the collection) is ample evidence of pseudoautotomy (Slowinski & Savage 1995), as in D. dichrous .

Although morphometric data did not show the presence of sexual size dimorphism in D. brazili , examined males has on average longer SVL than females (mean 870 mm versus mean 856 mm).

Etymology: The specific name brazili honors Vital Brazil Mineiro da Campanha, well known as the discoverer of the species-specificity of antivenoms, founder of the Instituto Butantan and its director when Gomes (1918) described the species. Vital Brazil developed a system by which the Butantan sent antivenom kits to farmers and ranchers in exchange for live snakes that were freely shipped to the institute by the railroad lines (Adler 2007). This system provided in a few years a snake collection of thousand of specimens to Butantan including the type series of Drymoluber brazili . One disadvantage was the fact that the specific locality of collected specimens could not be certified, and they were labeled as being from the railway stations from where they were sent to the institute (see information about the holotype and paratypes above).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |