Prosorhynchoides thomasi, Bott, Ashley Roberts-Thomson Nathan J., 2007

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.177276 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6252026 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03C7879D-060B-DA1C-92DC-F1C1FB14A7AF |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Prosorhynchoides thomasi |

| status |

sp. nov. |

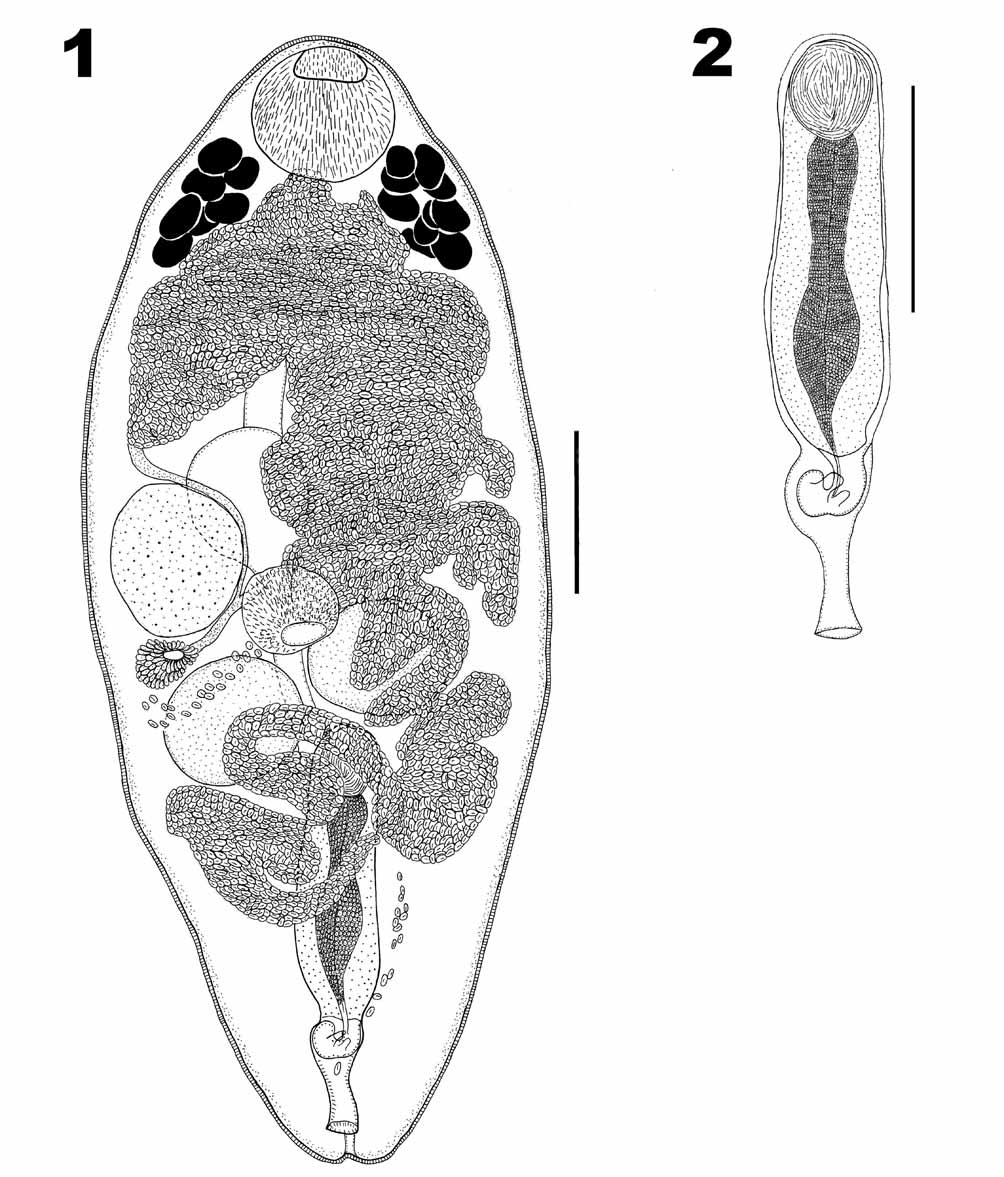

Prosorhynchoides thomasi View in CoL n. sp. ( Figs. 1–2 View FIGURES 1 – 2 )

Type host: Plagiotremus tapeinosoma (Bleeker) . Prevalence: 55% (6/11) Other hosts: Plagiotremus rhinorhynchos (Bleeker) . Prevalence: 85% (5/6)

Site of Infection: Intestine

Type Locality: Lizard Island, Australia (14°40’S, 145°20’E)

Deposition of Specimens: Queensland Museum, Brisbane, Australia; Holotype QM G227597, Paratypes QM G 227598-227606

Etymology: This species is named after our friend and colleague, Mr Rick Thomas for all his encouragement and support.

Description ( Figures 1 & 2 View FIGURES 1 – 2 ). Based on 11 whole-mounts. Body ellipsoidal, 1120–1496 (1289) × 272–560 (407), tegument spiny. Rhynchus a simple muscular sucker, 128–183 (161) long × 141–183 (162) wide. Mouth ventral, at midbody; pharynx, spherical 87–148 (116) long × 96–145 (115) wide. Caecum, sac-like, extends anteriorly beyond anterior margin of ovary, 170–331 (213) long.

Testes, two, round, symmetrical, between pharynx and posterior extremity of body, with anterior testicular margin occasionally overlapping pharynx; anterior testis 93–173 (142) long × 96–173 (144) wide; posterior testis 100–170 (137) long × 100–180 (142) wide. Cirrus-sac ( Figure 2 View FIGURES 1 – 2 ) median to sinistral, 308–475 (367) long × 70–106 (89) wide, extending to mid-level of posterior testis. Seminal vesicle ovoid 37–80 (61) long × 48–167 (82) wide, within proximal portion of cirrus-sac. Pars prostatica straight, highly glandular, 241–286 (261) long, joins with seminal vesicle. Ejaculatory duct narrow, short. Genital atrium ovoid containing hook-shaped genital lobe with 2 projections. Common genital pore median ventro-subterminal.

Ovary, pre-testicular, spherical, 98–173 (139) long × 105–183 (147) wide, antero-dextral to pharynx, 562–784 (642) from posterior extremity. Mehlis’ gland dextral, between posterior testis and ovary. Laurer’s canal not seen. Vitelline follicles forming two compact lateral groupings at level of posterior third of rhynchus, extending anteriorly to 109–164 (133) from anterior extremity. Vitelline ducts open into öötype within Mehlis’ gland. Uterus voluminous and convoluted, ascending sinistrally to level of vitelline follicles, then descending and opening into genital atrium. Eggs numerous, tanned, oval 13–22 (18) long × 7–12 (10) wide. Excretory pore terminal. Excretory vesicle I shaped, extending to anterior quarter of body.

Discussion. Prosorhynchoides Dollfus, 1929 includes a large number of species grouped together due to the common feature of having a simple sucker for a rhynchus and pre-testicular ovary ( Overstreet and Curran, 2002). The present species conforms to this diagnosis. The genus is in need of a major revision (see Overstreet and Curran, 2002) and has received some attention recently ( Bott and Cribb, 2005a; Bott and Cribb, 2005b) though further disentanglement of the various synonymies is required. Bucephalopsis Diesing, 1855 , Neobucephalopsis Dayal, 1948 and Bucephaloides Hopkins, 1954 are considered junior synonyms of Prosorhynchoides (see Overstreet and Curran, 2002). Within Prosorhynchoides , gut morphology is considered important for species differentiation ( Overstreet and Curran, 2002). An important distinguishing feature of the present species is the testes, which are symmetrical. Only eight of the sixty-three species that we can find assigned to Prosorhynchoides , Bucephalopsis , Neobucephalopsis and Bucephaloides possess testes that are symmetrical or nearly symmetrical. We compared figures and descriptions of these seven to the present species. Of these, the unusual specimen of Prosorhynchoides gracilescens (Rudolphi, 1819) (with symmetrical rather than tandem testes) reported by Bartoli et al.(2006), Prosorhynchoides garuai (Verma, 1936) Bott & Cribb, 2005 , Prosorhynchoides productiovalis (Lebedev, 1968) Bott & Cribb, 2005 , Prosorhynchoides magnum (Verma, 1936) Bott & Cribb, 2005, Prosorhynchoides mehrai (Agarwal & Agarwal, 1986) Bott & Cribb, 2005 and Bucephalopsis rhynchobati Wang, 1985 , differ from our specimens by having posteriorly rather than anteriorly directed caecum. We propose B. rhynchobati Wang, 1985 , be recombined with Prosorhynchoides to become Prosorhynchoides rhynchobati (Wang, 1985) Roberts-Thomson & Bott , n. comb. as it conforms to the diagnosis of Prosorhynchoides . Prosorhynchoides gauhatiensis (Gupta, 1953) Bott & Cribb, 2005 , and Prosorhynchoides thapari (Dayal, 1948) Bott & Cribb, 2005 , both have a caecum directed anteriorly like in the present species. However, their caeca recurve anteriorly. Both species also have ovaries situated anterior to the caecum whereas the ovary of P. thomasi n. sp. is always posterior to the anterior extremity of the caecum. Specimens examined were morphologically distinct from other members of the genus and justify distinct species status.

Dyer et al. (1988) examined specimens of Plagiotremus tapeinosoma and P. laudandus finding bucephalids that were identified as Prosorhynchoides koreana ( Ozaki, 1928) Bott & Cribb, 2005 , and specimens were not figured or described. Although, on initial inspection, bucephalids found in the present study appear similar to P. ko rea na, they exhibit a number of differences. The caecum in the new species extends anteriorly from the pharynx, whereas in P. k o re - ana, it initially extends anteriorly then turns posteriorly with caecal termination posterior to the pharynx. The genital pore in P. koreana is sinistral whereas in the present species the genital pore is median. Additionally, P. koreana has ovary and testes posterior to the pharynx, whereas the current species has an ovary extending anteriorly to the pharynx. Prosorhynchoides koreana was described from the fresh water catfish, Silurus asotus ( Ozaki, 1928) . We suggest that examining the specimens of Prosorhynchoides from Plagiotremus laudandus from Okinawa, Japan would be of interest to assess if they are conspecific with P. th oma si n. sp. or indeed a new species. Currently the habitat range reported for P. koreana (fresh and seawater) is exceptional and would pose interesting questions about the identity of suitable intermediate hosts.

Adoption of what can be termed traditional bucephalid transmission (larger fish eating smaller fish) has also been observed in the cleaner wrasse: Labroides dimidiatus , L. bicolour and Bodianus axilaris ( Jones et al., 2003; Jones et al., 2004). The mimicry of cleaner wrasse colouration and behaviour is strikingly apparent within the genus Plagiotremus . By mimicking cleaner wrasse, fang blennies are able to approach fish in the same manner as cleaner wrasse. Members of this genus were found primarily at cleaning stations and were frequently observed darting in to feed on cleaner wrasse ‘clients’. Cleaner wrasse have become hosts to bucephalids by cleaning ‘clients,’ or nipping fins, flesh, or mucus ( Jones et al., 2004). Plagiotremus species undertake only micropredatory behaviour, with a diet of mucous, scales and fins (Randall, 1990). The bucephalid faunas of fang blennies and cleaner wrasse differ. Bucephalids from the genus Rhipidocotyle are found in cleaner wrasse and while R. labroidei Jones, Grutter & Cribb, 2003 exploits the symbiotic relationship between cleaner wrasse and their ‘clients’, P. thomasi n. sp. exploits the mimicry of cleaner wrasse by Plagiotremus spp.

This study also included examination of 86 other blennies from 15 species from the northern (Lizard Island) and southern (Heron Island) Great Barrier Reef. Three other species of the tribe Nemophini were examined with no digeneans being found in the intestines of eight specimens of Petroscirtes fallax , three specimens of Meiacanthus lineatus and two specimens of Meiacanthus grammistes . It is plausible that this transmission pathway is unique within the Blenniidae to the tribe Nemophini and further restricted to the genus Plagiotremus . It is interesting to note that P. thomasi n. sp. was not found from the southern Great Barrier Reef (Heron Island) even though the type-host, Plagiotremus tapeinosoma , was examined on three occasions.

Bucephalid definitive hosts are known to include piscivorous members of the Apogonidae , Carangidae , Scombridae , Sphyraenidae and Serranidae on the Great Barrier Reef. The dietary adoption of fin biting by fang blennies has allowed the Bucephalidae to colonise an unlikely host family in the Blenniidae .

Acknowledgements. The authors wish to thank the staff of Lizard and Heron Island Research Stations. Dr Tom Cribb, Tavis Anderson, Saioa Martinez, Pete Cook, Dr Matt Nolan, Conor Jones, Jon Yantsch, Bart McKenzie, Dr Gaines Tyler and Dr Gaby Munoz from the University of Queensland for their advice and assistance with collections. Dr Craig Hayward (University of Tasmania) kindly made comments about an earlier draft of the manuscript.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

SubClass |

Digenea |

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |