Placospherastra antillensis

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.187789 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6221848 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03C087B0-AE78-FFFD-FF1F-F925D899F864 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Placospherastra antillensis |

| status |

|

Placospherastra antillensis n. g., n. sp.

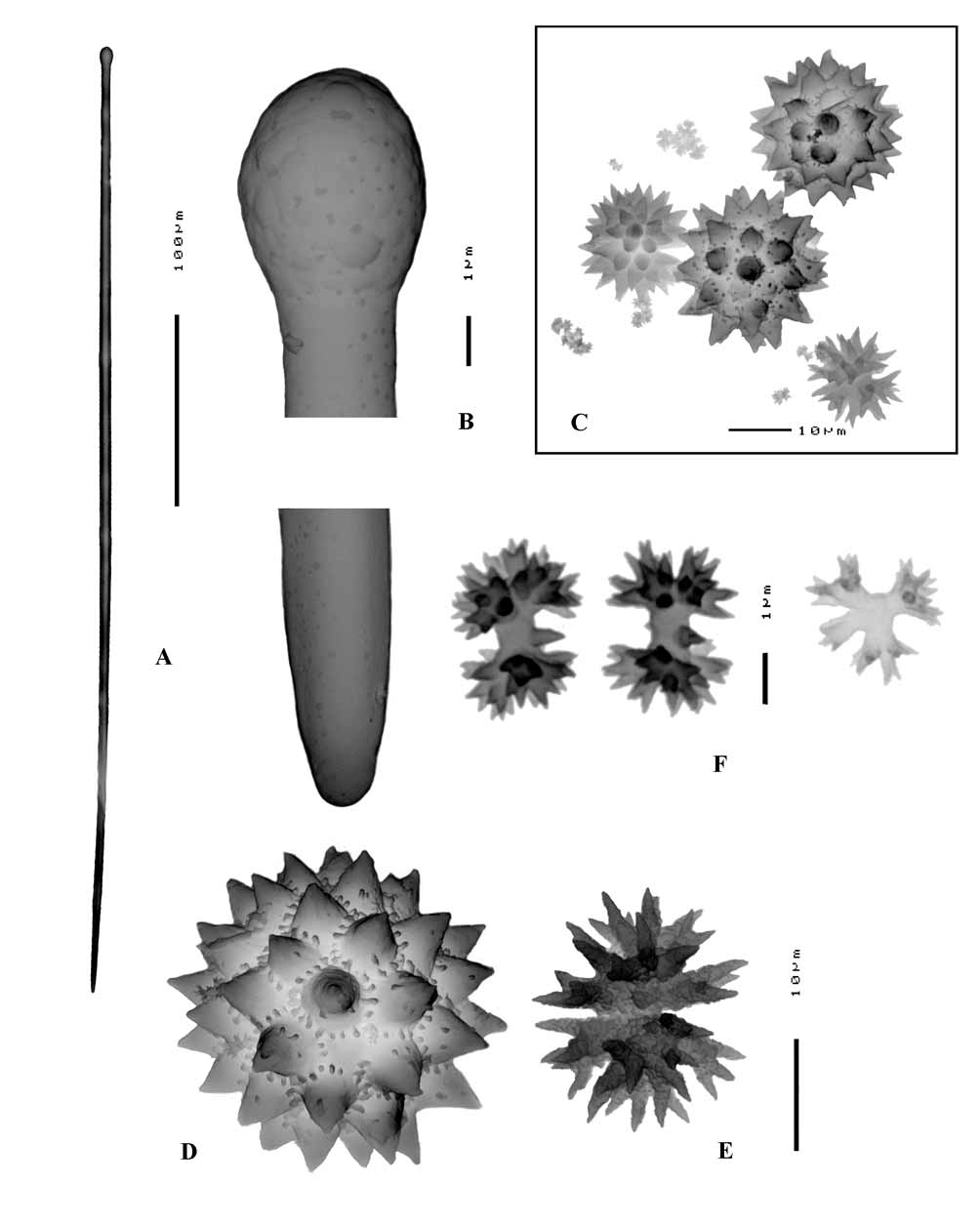

( Figs 2 View FIGURE 2 A–E, 3A–B)

Holotype. ZMA Por. 0 8973, Netherlands Antilles, Bonaire, Red Slave 2, 12.034°N - 68.259°W, 23 m, 20-08- 1987, coll. G.J. Roebers #202.

Paratypes. ZMA Por. 0 8974, Curaçao, Blauwbaai, under rubble, 12.131°N - 68.987°W, 35 m, 2-1989, coll. E. Meesters & P. Willemsen; ZMA Por. 21077, Curaçao, SeaQuarium, 12.081°N - 68.8919°W, 25 m, 1991, coll. M. Kielman #S64.

Additonal material (not belonging to the type series). ZMA Por. 0 8487, Bonaire, reef caves, 12–43 m, 1984, coll. D. Kobluk; ZMA Por. 13716 & 14085, Curaçao, Buoy 0, 12.124°N - 68.974°W, in reef caves, 01- 1999, coll. I. Wunsch; ZMA Por. 19063, Curaçao, Buoy 3, 12.136°N - 68.97°W, reef, 2006, coll. N. van der Hall; ZMA Por. 0 8879, U.S. Virgin Islands, St. Croix, Cane Bay, 17.7417°N - 64.7392°W,1990, coll. W. Gladfelter; ZMA Por. 0 3347, Puerto Rico, off Mayaguez, 18.25°N - 67.225°W, dredged at 60–75 m, bottom muddy sand, 21-02-1963, coll. J.H. Stock.

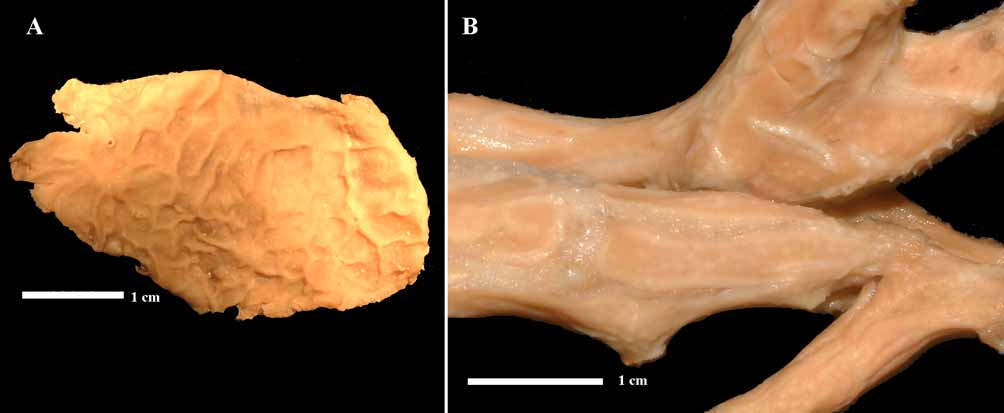

Description. Thick encrustations with Placospongia -like surface of elongated polygonal plates, separated by meandering ridges below which thin pore grooves are situated ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 A). The system of plates and ridges is irregular and forms a maze, with few ridges entirely enclosing the plates. Size of holotype 5 x 2.5 cm, thickness 1–5 mm. Color in life orange, dark orange, brown-orange or more yellow; in alcohol pale yellow or off-white. Consistency hard, rough to the touch.

Skeleton. Distinctly zoned similar to the skeleton of Placospongia . A dense ectosomal layer of spherasters forms the surface of the polygonal plates. These are surrounded by strong columns of tylostyles rising up from the bottom of the sponge supporting the plates and forming the sides of the meandering pore grooves, in which they also protrude slightly causing the sides of the grooves to be elevated. No clear separation or localization of a smaller and a larger category of tylostyles is apparent, but the tylostyles have a large size range (see below). Subdermal tissue between the columns with few spherasters, scattered ‘diplasters’ and densely distributed microspirasters forming a distinct fibrous layer devoid of heavy spiculation. At the bottom of the sponge a thin layer of spherasters lines the boundary with the substrate.

Spicules. Tylostyles, spherasters, ‘diplasters’, microspirasters/amphiasters.

Tylostyles ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 A–B), with prominent elongated heads, often annulated beneath the tyle, in a large size range,, 162- 428.6 -578 x 3.5- 5.4 -8 µm.

Spherasters ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 D and part of C), globular, with short conical rays, in full-grown condition ornamented with little blunt spines in a ring around the base of the cones, 27- 28.6 -31 µm in diameter.

Diplasters ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 E and part of C), elongated with an often one-sided constriction in the middle, with long conical rays, with crenulated surface, 14- 17.8 -21 µm. Possibly these are juvenile forms of the spherasters, in which case, nonetheless, one would expect to find more intermediate forms.

Micramphiasters, microspirasters, and related forms ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 F and part of C), tiny, with short rhabds and composite rays, often a bit irregular in shape, 2– 4.5 µm in length.

Ecology. Usually under coral rubble and in reef caves, 20–23 m; occasionally exposed in deeper locations.

Etymology. The genus name refers to the placospongia-like aspect of the surface and to the spherasters that replace the placospongiid selenasters. The species name indicates the so far Antillean occurrence (both Lesser and Greater Antilles) of the species.

Remarks. With this new genus the family Placospongiidae , until recently monotypical, consists now of three genera. Placospongia Gray (1867a) so far has six species, while Onotoa de Laubenfels (1955b) has two species, and the new genus Placospherastra so far has one species (but see below). All three genera are closely similar in outlook and skeletal structure, making membership of a single family quite obvious, but possession of selenasters, until recently considered a strong synapomorphy for the family, is now restricted to the genus Placospongia . The two other genera lack selenasters and have instead amphinolasters (genus Onotoa ) or globose spherasters ( Placospherastra n. g.) in the same position, i.e. making up the surface armour. The new species was previously identified as an undescribed Placospongia , but to accommodate it within this genus would widen the defintion too far. Following the erection of Onotoa for placospongiid species with a replacement spicule type for the surface armour, it is proposed here to erect a separate genus for placospongiid sponges with yet another replacement spicule type. One could argue that this is unnecessary, since the lack of selenasters may be merely a loss, and the remaining spicules all occur in one or more true Placospongia species. Placospongia species frequently have tiny (2–3 µm diameter) spherasters lodged in the spaces among the selenasters at the surface. In Placospongia melobesioides Gray (1867a) from Borneo, P. melobesioides sensu Arndt (1927) from Curaçao, P. intermedia Sollas (1888) from the Caribbean end of the Panama Canal, and P. cristata Boury-Esnault (1973) from Brazil, a complement of medium-sized spherasters occurs in the choanosome, looking surprisingly similar to golf balls in SEM images. In Placospongia decorticans ( Hanitsch, 1895) , spherasters of 16 µm diameter apparently form an extra surface armour on the outside of the layer of selenasters, which could indicate that the surface structure in P. antillensis n. g., n. sp. is induced by loss of the selenasters and the need for a replacement structure. Of the true Placospongia species, P. decorticans resembles P. antillensis n. g., n. sp. closest, sharing most spicule types. The same observations apply mutatis mutandis to differences between Placospongia and Onotoa , but the case for the latter genus is stronger since there are two species sharing the same surface spicule types. It is expected that more species lacking selenasters and having a surface armour of globose spherasters will be found to exist (see below). A further argument for keeping the new species in a genus of its own, is that the spherasters are morphologically distinct from those of P. melobesioides and P. decorticans in having an ornamentation of small spines encircling the conical rays. Possibly the term spheraster in this case does not cover homologous spicule forms.

A somewhat deviating specimen ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 B) of the new species, or possibly a representative of a second species of the new genus, is here recorded from a non-sciophilous muddy deep water habitat off the west coast of Puerto Rico (ZMA Por. 0 3347, details listed above). The sponge is seemingly branching, with branches 6 cm long and 0.5–1 cm in diameter, but cross section of the branches showed that the centre is formed by dead bryozoan material, indicating that the sponge is encrusting. Color was given as vermillion by the original collector, in alcohol it is yellow-brown. A striking feature are the white striated grooves separating the polygonal plates, which are much wider (4–5 mm) than in the sciophilous specimens described above ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 B). The spicules are generally similar to those of the sciophilous specimens, but sizes of tylostyles (up to 600 x 10–12 µm) and spherasters (32–40 µm) are on the upper side of the range or exceeding those of the type and paratypes. In spite of this and in spite of the unusual live color, for the time being the specimen is treated as a somewhat extreme specimen of the new species.

Four other species of Placospongiidae were recorded from the Central West Atlantic: Placospongia carinata ( Bowerbank, 1858) , P. melobesioides Gray (1867a) , P. intermedia Sollas (1888) and P. cristata Boury-Esnault (1973) .

Placospongia carinata was recorded by Little (1963) from the Gulf of Mexico, Pulitzer-Finali (1986) from Jamaica, Hechtel (1976), Coelho & Mello-Leitão (1978) and Rua et al. (2006) from Brazil. We report here material from sciophilous habitats along the Caribbean coast of Colombia, (ZMA Por. 21078, Cartagena area, Islas del Rosario, Isla Pavitos, 10.2333°N - 75.75°W, 15 m, 30-IX-1990, coll. M. Kielman, #S29; ZMA Por.

20871, Colombia, Cartagena area, Islas del Rosario, Isla Pavitos, 10.2333°N - 75.75°W, 5 m, 30-IX-1990, coll. M. Kielman, #S71), and from Grenada (ZMA Por. 0 7643, St. Georges, 12.044°N - 61.749°W, 5 m, 05-03- 1986, coll. J.J. Vermeulen #86-122). Since the specimens do not entirely conform with descriptions of the type from Borneo, Indonesia, a short combined description of the ZMA material is given here to aid future decisions about the status of the Caribbean populations: Brown encrustations, 5 mm in thickness, lateral expansion indefinite, at least 5 cm. Surface ‘veined’ by a combination of polygonal plates and pore-bearing grooves. Skeleton: Ectosomal crust of selenasters carried by a palisade of smaller tylostyles; sides of the grooves fortified by strong bundles of larger tylostyles which traverse the body down to the substrate. Selenasters are cemented by a dense mass of microrhabds/microspirasters. Subectosomal space between the megasclere bundles with a mixture of microrhabds and amphiasters. Spicules: tylostyles in two size categories, selenasters, juvenile selenasters, amphiasters/spirasters possibly divisible in two types, acanthomicrorhabds. Large tylostyles with prominent tyles and usually bluntly rounded apices, 669- 875. 3- 1069 x 12 - 15.3 -20 µm; small tylostyles, not overlapping with large tylostyles, 170- 263.5 -330 x 6-7 µm. Selenasters, ellipsoid-rounded, 54- 79.3 -90 x 37 - 65.1 -72 µm; juvenile selenasters, bean-shaped with spines irregularly distributed, 36- 39.8 - 48 x 18 - 23.2 -30 µm. Amphiasters, with a straight rhabd and 3–4 terminally branched rays at each end, each ray with two –three terminally branched secondary rays, with or without fine spines on rhabd and rays, size of rhabd 12- 16.2 - 19 x 3–4 µm, of rays 6– 9 x 1.5 µm; spirasters, similar in size to amphiasters, but with rays distributed along the rhabd, which is spirally curved. Acanthomicrorhabds, undulate or with faint spiral twist, 6- 8.6 - 15 x 1–2 µm. The specimens described here are at first glance assignable to Placospongia carinata Bowerbank (1858) s.l. This species was originally described from the ‘South Seas’, presumably the South Pacific Ocean, a considerable distance away from the South Caribbean. It has become customary to consider Placospongia specimens with ‘spirasters’ as members of a cosmopolitan species. However, the present specimens have the sizes of at least two spicule types clearly different from the type specimen of P. carinata and this could be interpreted as evidence of specific distinctness. ‘Spirasters’ measure 35–40 µm in the type and thus are twice as large as the amphiasters/spirasters of the Caribbean material (12–19 µm), while the acanthomicrorhabds in the type measure 20 µm against 8–15 µm in our Caribbean specimens. The morphology of the spirasters/amphiasters in both are also clearly distinct, with those in South Pacific P. carinata with robust thick rhabd and long irregularly branched rays, and those of the Cariibean specimens with thinnish rhabd and shorter rays. Possibly, these streptasters are divisible in two distinct types, one more amphiaster-like, the other more spiraster-like, but this needs to be established in more specimens from various localities in the Caribbean. Other records of P. carinata from various parts of the world also show discrepancies from the type description: for example larger (Lindgren, 1897) or less branched spirasters ( Green & Gómez, 1986), two size categories of acanthomicrorhabds ( Vacelet & Vasseur, 1965), much smaller tylostyles ( Lévi, 1956). This indicates in our opinion a much higher diversity of Placospongia than currently recognized in specimens assigned to P. c a r i n a t a dating back from Vosmaer & Vernhout (1902). I predict that the ‘variability’ in spicule categories and sizes is caused by the occurrence of several more species in this species complex.

Placospongia melobesioides Gray (1867a) specimens, recorded from the Central West Atlantic originated from Florida, Curaçao and Campeche ( Schmidt, 1870; Arndt, 1927; de Laubenfels, 1936a; González-Farías, 1989), may be attributable to a separate regional species, P. cristata Boury-Esnault (1973) originally described from Brazil. Rützler (2002a) suggested this to be a synonym of P. melobesioides , but apart from the large geographic separation of the original locality (Borneo) and the Central West Atlantic, there is also a consistent difference in the upper size of the tylostyles (up to 1200 µm in the type specimen against up to 900 µm in the Central West Atlantic material identified as P. melobesioides and P. cristata ). It is likely that such differences are attributable to specific distinctness. There are a few discrepancies between the descriptions of Arndt (1927) and Boury-Esnault (1973), as Arndt denies the presence of spherasters in his specimens, whereas Boury-Esnault does not mention the presence of microspherasters. The specimens of Arndt were reexamined as they are in the collections of the Zoölogisch Museum of the University of Amsterdam (ZMA Por. 0 1816 and 0 1817, both from Spaanse Water, Curaçao). They contain spherasters of 15–18 µm, of the typical ‘golf-ball’ shape, so Arndt’s specimens do conform to Boury-Esnault’s description in that respect. It is assumed that microspherasters or spheres are present in the type material of P. cristata , but this needs to be demonstrated. P. melobesioides is also recorded from Northern Brazil ( Mothes et al. 2006), and these authors provide SEM images of the spicules, as well as measurements. It appears as if this is yet again a different form, deviating from the type specimens of P. melobesioides and from P. cristata in the lack of the discussed medium-sized (‘golf-ball’) spherasters. Instead, the specimen possess microspirasters similar to those of Placospherastra antillensis n. g., n. sp.

P. intermedia Sollas (1888) as recorded from the Caribbean end of the Panama canal by de Laubenfels (1936b) deviates strongly from the desciption of Sollas (1888). Possibly this concerns a further separate as yet undescribed species of Placospongia . Color reported by de Laubenfels was orange (chocolate brown in the type of P. intermedia ), selenasters were only 35– 50 x 20–35 µm (64 x 58 µm in the type), spherasters of 1–8 µm diameter (in fact these are probably microspherasters or spheres, whereas Sollas reports spherasters of 20 µm diameter). Other features are similar in both. Sollas’ material was from the Pacific side, whereas de Laubenfels reported his specimens from both sides of the isthmus, while his spicule data were apparently taken from the Caribbean specimens. P. intermedia was also listed by Díaz (2005) from Bocas del Toro, Panama, but no description was provided. Lehnert & van Soest (1996) incorrectly assigned the Jamaican specimen described by Pulitzer-Finali (1986) as P. c a r i n a t a to P. intermedia .

In summary the status of records of placospongiids from the Central West Atlantic is as follows: (1) Placospongia carinata sensu Little (1963) , Hechtel (1976), Coelho & Mello-Leitão (1978), Pulitzer-Finali

(1986) (including citation of Lehnert & van Soest, 1998), Rua et al. (2006), and unpublished specimens

from the ZMA collection mentioned above = Placospongia sp. 1 (not: P. carinata ( Bowerbank, 1858) (2) Placospongia melobesioides sensu Schmidt (1870) , Arndt (1927), de Laubenfels (1936a), González-Farías

(1989) =? P. cristata Boury-Esnault (1973) (not: P. melobesioides Gray, 1867 a)

(3) Placospongia cristata Boury-Esnault (1973) = valid species, see also above.

(4) Placospongia melobesioides sensu Mothes et al. (2006) = Placospongia sp. 2 (not: P. melobesioides Gray,

1867a)

(5) Placospongia intermedia sensu de Laubenfels (1936b) = Placospongia sp. 3 (not: P. intermedia Sollas,

1888)

(6) Placospherastra antillensis n. g., n. sp. = valid species.

Scott & Barnes (2005) performed sequence analysis of a world-wide set of Placospongia specimens, not further identified to species. Their conclusions were that more genetic differentiation is found than would be expected if there were only two or three cosmopolitan ‘species’. Our critical comparison of spicule sizes and types appear to support the conclusions of the genetic research.

Several hadromerid species possessing tylostyles and spherasters occur in the Central West Atlantic. For completeness sake we present an overview to demonstrate they are not conspecific with our new species. Paratimea galaxa de Laubenfels (1936a) from Florida differs in lacking the surface plates and possessing tornotes in addition to the tylostyles and the spherasters. Columnitis squamata , also from Florida, as described by Schmidt (1870) reminds of our new species in having polygonal surface ornamentation, but redescription by Sarà & Bavestrello (1996), made it clear that this is a tethyid genus and species (after previously having been assigned to the synonymy of Timea by de Laubenfels, 1936a) showing little in common with our new species.

The definition of the new genus resembles that given by de Laubenfels (1936a) for the genus Kotimea , with type species Hymedesmia moorei Carter (1880, from the Gulf of Mannaar, India). The precise affinity of Carter’s species with tylostyles and spherasters remains undecided because the type material is lost. There are no indications in Carter’s description that the surface would have had armoured placospongiid plates. Rützler (2002b) assigned Kotimea to the synonymy of Timea Gray (1867b) . A second species assigned to Kotimea , Hymeraphia spiniglobata Carter (1879) is a Diplastrella , while Kotimea tethya de Laubenfels (1954) is a Timea .

| ZMA |

Universiteit van Amsterdam, Zoologisch Museum |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Placospherastra antillensis

| Van, Rob W. M. 2009 |

P. cristata

| Boury-Esnault 1973 |

Placospongia carinata sensu

| Little 1963 |

P. intermedia

| Sollas 1888 |

Placospongia melobesioides

| Gray 1867 |

Placospongia carinata

| Bowerbank 1858 |