Rana arvalis Nilsson 1842

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5301.3.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9A64620A-5346-459A-9330-7E8AE9EBEBDE |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8030424 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03BE87CB-FF83-4A6D-B888-7DB34028FD4C |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Rana arvalis Nilsson 1842 |

| status |

|

Moor Frog Rana arvalis Nilsson 1842 View in CoL View at ENA

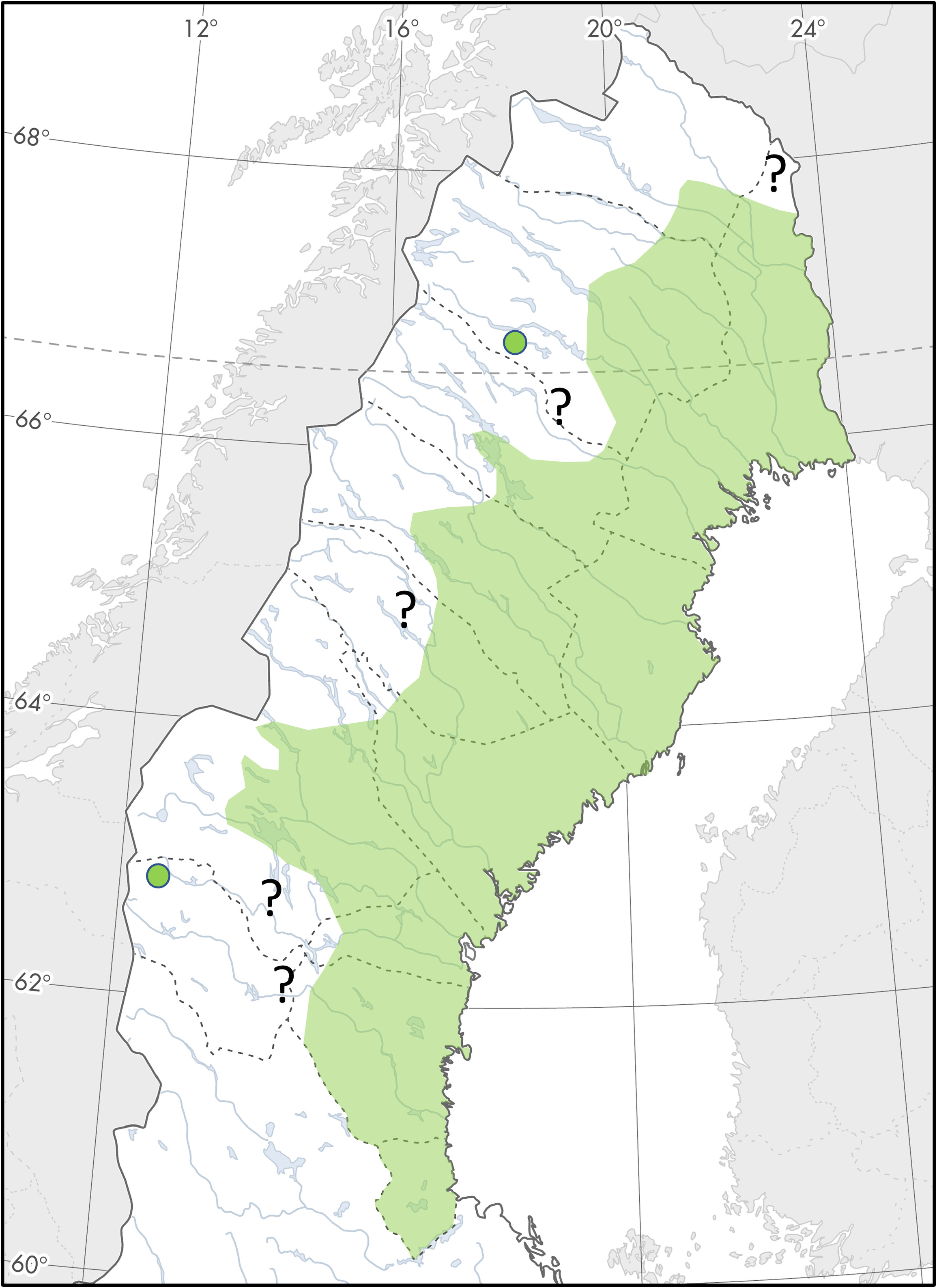

Distribution ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 ). Included records from Artportalen (N=650): as confusion with Rana temporaria is possible, reports from the Alpine region, the Northern Boreal region and all offshore sites were included only if substantiated by photos, concern calling males, or made by known experienced observers. Reports from the Southern and Middle Boreal were all included.

Widespread and common in the Southern and Middle Boreal. For unknown reasons more abundant in landscapes with flatter topography ( Sterner 2005; Elmberg 2008), a pattern also noted in Finland ( Terhivuo 1981). Widespread but less common in the Northern Boreal, scarce in its higher parts. The northernmost Swedish record is at Kulijärvi, Torne lappmark ( 67° 50’ N, 21° 40’ E; Elmberg 1984). Previous records from the Alpine region (e.g., Elmberg 1995) are now considered as unconfirmed and not valid.

The highest known records are very close to the border between the Northern Boreal and the Alpine regions: 580–600 m altitude at Danasjö-Abborrberg (Lycksele lappmark; Anders Forsgren personal communication) and 510 m at Årjep Kuossåive (Lule lappmark; Elmberg 1995; shown as an isolated occurrence in Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 ).

Offshore occurrence of this species in the Baltic is a puzzling topic. Before the period covered here, Curry-Lindahl (1956) collected specimens on Haparanda Sandskär ( Norrbotten), an island situated a staggering 32 km from the mainland. It has not been found there since. There are several recent reports in the Artportalen reporting platform (see Methods) from the offshore Holmön archipelago ( Västerbotten), but none is convincingly documented. To conclude, there are no recent records of this species on truly offshore islands anywhere along the Baltic coast of North Sweden. This suggests a much lower dispersal capacity over brackish water than in the two other anuran species.

There are no indications of changes in distribution over the last 50 years. It should be noted, though, that the true range and abundance in North Sweden was grossly underestimated until the 1970’s ( Gislén & Kauri 1959 versus Elmberg 1978; 1984; 1995; 2008). The near-Alpine record from Härjedalen presented here ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 ; photograph in Artportalen) is the first from the province.

Habitat and movements. Spring migration usually starts 5–10 days later than in Rana temporaria ( Elmberg 2008) . Adult male Rana arvalis migrate to breeding sites in a strongly synchronized fashion during a few nights, whereas adult females have a more protracted spring migration. Juveniles are rarely seen before the end of the breeding season.

Breeds in a wide variety of wetland habitats: open mires, grassy bogs, forest lakes, flooded riverine meadows, deciduous bottomland forest swamps, and shallow brackish bays of the Baltic ( Elmberg et al. 1979; Elmberg 2008; Figures 11 View FIGURE 11 , 14 View FIGURE 14 ). Anthropogenic breeding sites include eutrophic ponds in agricultural settings as well as flooded disused gravel pits and quarries. Breeding Rana arvalis have an affinity for more richly vegetated wetlands than do the other two anurans, although spawning per se generally occurs in somewhat deeper water than in Rana temporaria ( Elmberg 2008; cf. Ruuth 2017). Females remain in the breeding wetlands only until they have deposited their eggs, whereas adult males stay as long as receptive females are around, or longer ( Elmberg 2008).

Dispersal from breeding sites to nearby summer foraging habitats is gradual and not very conspicuous. Summer habitats are varied, yet more restricted to well-vegetated and damp conditions than in Rana temporaria . In effect, Rana arvalis are rarely encountered in coniferous forest in summer, but more often in lush deciduous forest with a rich understory ( Figure 18 View FIGURE 18 ). However, most spend the summer in natural meadow-like habitats along lakes, rivers, and seashore, or in open grassy or willow-dominated habitats in forest clearings ( Figure 13 View FIGURE 13 ). Although there are not any quantitative data from North Sweden to verify the claim, it appears that Rana arvalis spend the summer closer to breeding sites than do Rana temporaria and Bufo bufo (cf. Čeirâns et al. 2021). In some areas and habitats of the interior north, such as open mires, adults appear to be semi-aquatic, spending most of the summer on grassy shores of breeding wetlands ( Elmberg 2008; Figure 14 View FIGURE 14 ).

In North Sweden, movement in summer has only been studied anecdotally by individual mark-recapture, suggesting a high degree of site fidelity ( Elmberg 2008; see Ruuth 2017 for a telemetry study in nearby Finland documenting habitat preferences and movement distances).

Autumn migration to hibernation sites is sometimes conspicuous and synchronized, triggered by rains or mild cloudy conditions, and generally occurs a week or two earlier than in Rana temporaria .

Hibernation in North Sweden is aquatic, taking place in slow-flowing streams and rivers close to breeding sites, but sometimes in the latter or in nearby lakes. There, Rana arvalis seek out and settle in protective dense near-shore aquatic vegetation, thus often hibernating alongside Rana temporaria and Bufo bufo . Note, though, that this species is extraordinarily cold-hardy and that terrestrial hibernation has been documented in Finland and Russia ( Ruuth 2017; Berman et al. 2020). This may occur in North Sweden, too, although it has not yet been documented.

A fuller treatment in English of the ecology and natural history of Rana arvalis in North Sweden is found in Elmberg (2008).

Abundance estimates and trends. Throughout the 1980’s I studied a population in Umeå, Västerbotten, at a breeding site encircled by built-up urban areas (Tvärån: 63°49’50.9”N, 20°13’38.4”E). The GoogleMaps summer foraging habitat surrounding this pond comprises mid- to late successional riparian deciduous woodland (2.5 hectares; Figure 18 View FIGURE 18 ). Counts GoogleMaps of calling males and drift fence catch data permitted accurate annual estimates of the breeding population. Accordingly GoogleMaps , the density of adult frogs in the summer habitat was 35–60/hectare (3500–6000/km 2), depending on year. These GoogleMaps densities represent a habitat that is probably among the most benign for this species in North GoogleMaps Sweden. A more likely average abundance for North GoogleMaps Sweden in general is in the interval 400– 700 adults /km 2, with the lower densities in the Northern Boreal GoogleMaps and the hilly parts of the Southern Boreal. These landscape level abundance estimates are fairly similar to those for Rana temporaria , a notion supported by impressions from roadside surveys of calling anurans in the interior of North Sweden ( Elmberg 1984).

There are no indications of large-scale changes in abundance over the last 50 years ( Elmberg 2008).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.