Formica forsslundi Lohmander, 1949

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5392741 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03BB87B2-FFA1-F145-4ECF-FE87FD89FC65 |

|

treatment provided by |

Marcus |

|

scientific name |

Formica forsslundi Lohmander, 1949 |

| status |

|

Formica forsslundi Lohmander, 1949 View in CoL

Formica forsslundi Lohmander, 1949

TYPE LOCALITY. — Närke, Värmland, Västergötland, Sweden.

TYPE MATERIAL. — No types available in the museums of Göteborg and Stockholm [identification by original description].

Formica forsslundi strawinskii Petal, 1962 . Synonym.

TYPE LOCALITY. — Rakowskie Bagno near Frampol, district Lublin, SE Poland.

TYPE MATERIAL. — Paratypes worker and queen ( ZIPAS) [investigated].

Formica brunneonitida Dlussky, 1964 . New synonym. TYPE LOCALITY. — Cherulen Buudal, Mongolia.

TYPE MATERIAL. — Syntypes ( ZMLSU ZIPAS; MZ) [investigated] .

Formica fossilabris Dlussky, 1965

TYPE LOCALITY. — NE Tibet: southern coast of Lake Koko Nur [synonymy by original description of workers and by investigation of a worker sample from the locus typicus].

GEOGRAPHIC ORIGIN OF THE MATERIAL STUDIED. — The numerically evaluated 125 specimens ( 94 workers, 18 queens, 13 males) came from Sweden 27, Finland 33, Denmark 3, Germany 9, Poland 11 Switzerland 16, Caucasus 16, Mongolia 7, and N Tibet 3. Total number of specimens seen> 200.

DESCRIPTION

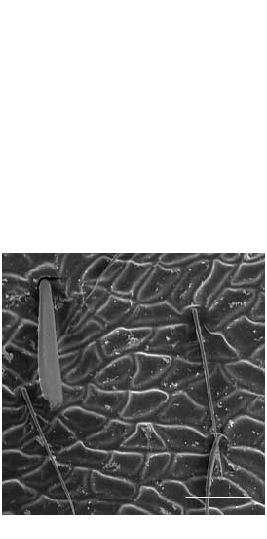

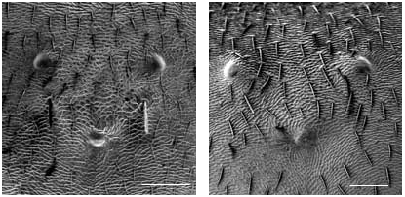

Worker ( Figs 2 View FIG ; 8 View FIG ; 11 View FIG )

Rather small (CL 1281 ± 70, 1024-1404). Head shape of average Coptoformica type (CL/CW 1.051 ± 0.018, 1.007-1.099). Scape rather short (SL/CL 0.987 ± 0.019, 0.944-1.035); in the Caucasian population extremely short (SL/CL 0.947 ± 0.023, 0.912-0.979). Clypeus only in anterior area with standing setae, caudal setae always absent (ClySet 1.84 ± 0.52,1-3). Clypeus lateral of the tentorial pit level frequently with few pubescence hairs surpassing the anterior margin by more than> 10 µm; in the Caucasian population such hairs are fully absent; ClyPub 1.31 ± 1.21, 0-6.0. Lateral semierect setae in the ocellar triangle in many specimens absent (OceSet 47%). Eyes usually without or with few microscopically short hairs, in the Mongolian and Tibetian samples few longer hairs are frequently present; EyeHL 6.6 ± 3.2, 0-25. Pubescence hairs in the occellar triangle extremely sparse (sqrtPDF 6.96 ± 0.84, 5.63-9.80; Fig. 11 View FIG ). Craniad profile of forecoxae usually with single semierect setae which are in the Caucasian population fully absent; nCOXA 1.31 ± 1.35, 0-4.5. Lateral metapleuron and ventrolateral propodeum as a rule without standing setae (nMET 0.01 ± 0.05, 0-0.5). Outer edge of the hind tibial flexor side with several semierect first order setae, second order setae absent ( Fig. 2 View FIG , nHTFL 5.82 ± 1.14, 3.0-8.5). Erect setae on gaster tergites usually beginning on the first tergite (TERG 1.16 ± 0.40, 1-3). Pubescence on first gaster tergite variable but usually very sparse (sqrtPDG 7.09 ± 0.55, 5.62- 8.24). Promesonotum frequently with a blackish patch with diffuse margin.

Queen

Size very small (CL 1223 ± 43, 1160-1307; CW 1248 ± 28, 1210-1299; ML 1885 ± 69, 1784- 2003). Head proportions without pecularities (CL/CW 0.980 ± 0.029, 0.911-1.022). Scape rather short (SL/CL 0.867 ± 0.019, 0.831- 0.897), in the two Caucasian queens extremely short (SL/CL 0.796,0.797). Clypeal setae restrict- ed to anterior portion, second level setae usually present. Erect setae in the ocellar triangle may be present. Eye hairs fully absent or very minute (EyeHL 6.2 ± 2.5, 0-10). Pubescence in the occellar triangle usually extremely sparse (sqrtPDF 5.95 ± 0.61, 4.80-6.96). Occipital corners of head with decumbent to appressed pubescence (OccHD 6.0 ± 6.4, 0-16). Dorsal head surface brilliantly shining (GLANZ 2.94 ± 0.16, 2.5-3.0). Craniad profile of forecoxae with few semierect setae, differentiation between setae and large pubescence hairs often difficult, making setae counts problematic (nCOXA 2.06 ± 2.54, 0-9.0). Dorsal mesosoma frequently with standing setae (MnHL 85.9 ± 54.1, 0-166). Outer edge of the hind tibial flexor side with several suberect to subdecumbent 1st order setae, second order setae absent (nHTFL 4.11 ± 1.89, 2.0-8.5). Erect setae on gaster tergites usually beginning on the first tergite (TERG 1.17 ± 0.38, 1-2). Pubescence on first gaster tergite sparse (sqrtPDG 6.73 ± 0.76, 5.06-8.07). Whole body smooth and shining, dark brown to blackish. Dorsal excision of petiole often deeply u-shaped.

TAXONOMIC COMMENTS AND

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The unavailability of types means no taxonomic risk in the case of forsslundi . The description of Lohmander (1949) and its statements on the peculiar habitat selection and nesting should leave no doubt which species is meant.

Four worker paratypes and one queen paratype of Formica forsslundi ssp. strawinskii Petal, 1962 from the bog Rakowskie Bagno in SE Poland do not differ in 13 numeric characters from the population means of Palearctic forsslundi . They only differ by above-average data of nCoxa and ClySet which are, however, fully within the range of variability known for forsslundi . Apart from the problem of describing a subspecies from a locality within the range of the nominal form, Petal (1962) presented no evidence of taxonomic significance for the proposed differential characters.

Twelve paratype workers of brunneonitida Dlussky, 1964 , labelled “ Mongolia, Cherulen Buudal, 120 km E Ulan Bator, 7.VI.1962, leg. Pisarski No. 3384” and two other worker samples from Mongolia and NE Tibet strongly suggest a synonymy of brunneonitida with forsslundi . Dlussky (1964, 1965, 1967) did not state any differential character to forsslundi . In fact, the investigations of this revision could not demonstrate a difference between 74 European workers of forsslundi (= nominal population) and the 10 available Mongolian and N Tibetian workers (= brunneonitida ) in the characters CL, SL/CL, TERG, nCOXA, nHTFL, nMET, sqrtPDF, sqrtPDG, ClySet, ClyPub, and OceSet even for the weak significancy level of 0.05 if tested in a t test. A weakly significant difference for p <0.05 is indicated for the larger CL/CW and EyeHL in the Central Asian population but the latter difference is not confirmed by a nonparametric U test. The following sequence of data compares the arithmetic mean ± standard deviation for brunneonitida (before the comma) and forsslundi (after the comma): CL 1274 ± 96, 1275 ± 67; SL/CL 0.992 ± 0.025, 0.987 ± 0.018; CL/CW 1.061 ± 0.015, 1.049 ± 0.017; EyeHL 11.7 ± 7.0, 6.1 ± 1.7; TERG 1.30 ± 0.48, 1.14 ± 0.38; nCOXA 1.00 ± 0.91, 1.53 ± 1.38; nHTFL 6.45 ± 1.14, 5.68 ± 1.06; nMET 0 ± 0, 0.02 ± 0.13; sqrtPDF 7.24 ± 0.84, 6.80 ± 0.58; sqrtPDG 7.34 ± 0.41, 7.01 ± 0.57; ClySet 2.10 ± 0.57, 1.88 ± 0.48; ClyPub 1.05 ± 1.23, 1.54 ± 1.17; OceSet 50%, 52%. These data provide no argument to maintain even a subspecies status of brunneonitida . The alleged differences between forsslundi and brunneonitida in the number of maxillary palp segments (Agosti 1989) have no taxonomic significance because specimens with five and six maxillary palp segments do occur syntopically (and even intranidally) in W Palaearctic forsslundi . Queens of brunneonitida were not available to the author but the structural and morphometric data given in the description of type material by Agosti are consistent with the characters of W Palaearctic forsslundi queens. Agosti stated as only diagnostic difference of the brunneonitida queen a “dorsally concavely excavated petiole which sides are never parallel”. Queens showing such petioles can be found in the European forsslundi population, e.g., in a sample from near Torskinge/ Sweden. Furthermore there is much probability for the species forsslundi to occur much farther in the East because it shows cold hardiness, can nest in mineralic soil, and is bound to the host species F. transkaucasica that is widely distributed all over the subboreal and alpine Palaearctic. The high similarities in habitat selection and zoogeography shown by Formica forsslundi and uralensis in the European range suggest that forsslundi could have a similarly wide Palaearctic range as the latter species. The easily recognized uralensis is known to have a continous range from subboreal W Europe to SE Siberia. The underrecording of forsslundi from Siberia seems to be more question of insufficient knowledge of determination characters or of the less eye-catching behaviour and nesting. The habit of preferentially nesting in temperate lowland Europe in peat bogs is, as in uralensis, a question of competitive displacement. Simple nests in mineralic soil without epigaeic mound constructions, as they were reported by Pisarski for the Mongolian type population of brunneonitida , are also observed occasionally in the W Palaearctic forsslundi population (Agosti 1989; Soerensen pers. comm.). As a consequence there is no morphological, biological, or zoogeographical argument for heterospecifity of brunneonitida from forsslundi .

Formica fossilabris Dlussky, 1965 has been described from a single worker sample collected by P. K. Kozlov at the southern coast of Lake Koko Nur/NE Tibet in August 1902. These types (said to be deposited in St Petersburg) were not available to the author. Instead a worker nest sample collected by A. Gebauer in the foot hills at the SW coast of Lake Koko Nur ( 37.00N, 99.53E, 3300 m) in June 1998 and the descriptions of type material by Dlussky (1965) and Agosti (1989) are used to infer a synonymy with forsslundi . According to these verbal descriptions and Dlussky’s drawings, the setae characters on clypeus, head, mesosoma, and gaster, the morphometrics, and the eye pilosity are in agreement with the conception of forsslundi presented above. Dlussky stated as diagnostic character of fossilabris “the middle of anterior part of the clypeus with triangular impression with an “alley” of hairs, widening towards the apex”. As already stated by Agosti and as stated above, clypeal shape is intraspecifically much too variable in Coptoformica to serve as diagnostic character and depressed triangular areas on anterior clypeus are no rare exceptions in W Palaearctic forsslundi . Dlussky’s drawing of the holotype shows that the “alley of hairs widening towards the apex” is nothing but an usual arrangement of first, second and third level setae on anterior clypeus. Such arrangements are occasionally found in W Palaearctic forsslundi and seem to be less rare in the Asian population. A triangular impression in anterior clypeus is clearly developed in all three examined topotypical workers (leg. Gebauer) and the setae arrangement depicted by Dlussky is seen in one of these specimens. This sample fully matches the character combination of forsslundi and has the following means: CL 1348, CL/CW 1.054, SL/CL 0.974, EyeHL 7.0, TERG 1.0, nCOXA 2.2, nHTFL 7.0, nMET 0.0, sqrtPDF 7.77, sqrtPDG 7.38, ClySet 2.0, ClyPub 0.5, OceSet 67%. Hence it is most probable that fossilabris is a synonym of forsslundi .

The forsslundi population found on subalpine pastures of the Caucasus is most certainly fully isolated and shows an extremely short scape, no projecting pubescence hairs on lateral clypeus and reduced coxal pilosity. The extreme scape character in this population could be considered to justify erection of a new taxon. This is contradicted, however, by the high coincidence with the Palaearctic main population in the majority of characters and by the sharing of the same specific host species. The problem needs further investigation.

BIOLOGY AND DISTRIBUTION

Geographic range

A more or less coherent population is found in the subboreal European range, that spreads from N Germany ( 55°N) across Denmark to Fennoscandia north to 66°N. The Asian range is poorly known but there is no zoogeographic or biocenotic argument that the Siberian, Mongolian and Tibetian populations should not be connected with the W Palaearctic population accross the continous belt of subboreal biomes within the range of the abundant host species F. transkaucasica . A more southern range in the N Alps and SE Poland is documented by few, isolated bog populations between 47 and 51°N, which most certainly represent glacial relicts. In the Caucasus, an isolated subalpine population is found between 1500 and 2500 m. Such a subalpine population is also suspected to exist in the Alps between 1300 and 2200 m but the author could so far not see a voucher specimen.

Habitat selection

In the European range, F. forsslundi represents a rather stenopotent species and is bound to different types of open bogs, wet heathland, or mesophilic sand dunes. In Fennoscandia, nests are preferentially situated on organic soil in wetter central and peripheral parts of peat bogs with different species of Ericaceae . Towards the south, more marginal Molinia stands on mineralic soil are preferred. In N Germany, a large population is found on semidry sand dunes with Deschampsia , Molinia , or Empetrum . The Caucasian population was found on subalpine to alpine pastures. In the cold steppes of Siberia, Mongolia and Tibet nest were found in xerothermous places on sandy soil with incomplete coverage of grasses but also in moister sitations near to the ground water level.

Status as threatened species

In Germany and Switzerland threatened by extinction (Red List 1). Protection of bogs and cautious habitat management in heathland or mesophilic sand dunes is critical for the survival of this species.

Colony foundation

Formica transkaucasica seems to be the exclusive host species of forsslundi throughout its whole range in Fennoscandia, Germany, Switzerland, the Caucasus, and Tibet. Nests in the wettest parts of peat bogs seem to be preferentially monogynous. Polycalic colonies were observed in the Caucasus and Poland but seem to be generally rare.

Nest construction

In wetter parts of peat bogs, nests are usually found in bults with the virtual nest being restrict- ed to a deep central cylinder that is typically roofed by a cover of Ericaceae leaves or white Eriophorum wool. The bult margin contains no nest galeries and is normally penetrated by Ericaceae , Eriophorum , and other grasses. Sometimes skewed “solar collectors” are construct- ed with plant material. Nests on mineralic soil are usually of the normal Coptoformica type made with finely-cut grass pieces. These nests have average dimensions of 20 × 20 cm (height × diameter) with the largest nests measuring 20 × 40 cm. Sörensen (1993) noted rather instable nest positions in sand dune areas with an average of 25% abandoned nests per year. In a Swiss Molinietum, repeated mechanical stress by mowing has apparently caused a restriction of the nest galeries to subterranean parts (Agosti 1989). In Asia, simple soil nests without epigaeic mound constructions were observed in grasslands on sandy soil (Dlussky 1967) but the nest found by A. Gebauer in a moister site at Lake Koko Nur showed a typical mound construction with organic material.

Development and microclimatic requirements

Not studied. The nest spots in Europe indicate a higher tolerance against humidity compared to related species. The N German population start- ed oviposition in mid April in the year 1998 (Soerensen pers. comm.).

Demography of nests and colonies

Only sparse information is available. Monogynous nests in bogs are not very populous: three nests excavated in Finland contained 500, 500, and 1500 workers. The largest population of forsslundi is known from the nature reserve Suederlueguemer Binnenduenen /N Germany with> 400 nests on 42 ha sand dune area and local densities of 84 nests/ha (Soerensen pers. comm.). No signs for polycaly (such as population exchange between the nests) were observed in this dense population.

Swarming

Not studied. Alates in the nests were found throughout the geographic range July 30.6 ± 9.9 d (July 15-August 25, n = 11).

| MZ |

Museum of the Earth, Polish Academy of Sciences |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |