Elosuchus, SP.

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1111/zoj.12452 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:8C546620-F729-42A8-A7F3-500DCA584B1C |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5710905 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03AEC940-FF8A-F506-FBC6-D2BDFA65FD2F |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Elosuchus |

| status |

|

Elosuchus felixi de Lapparent de Broin, 2002: 283 (partim).

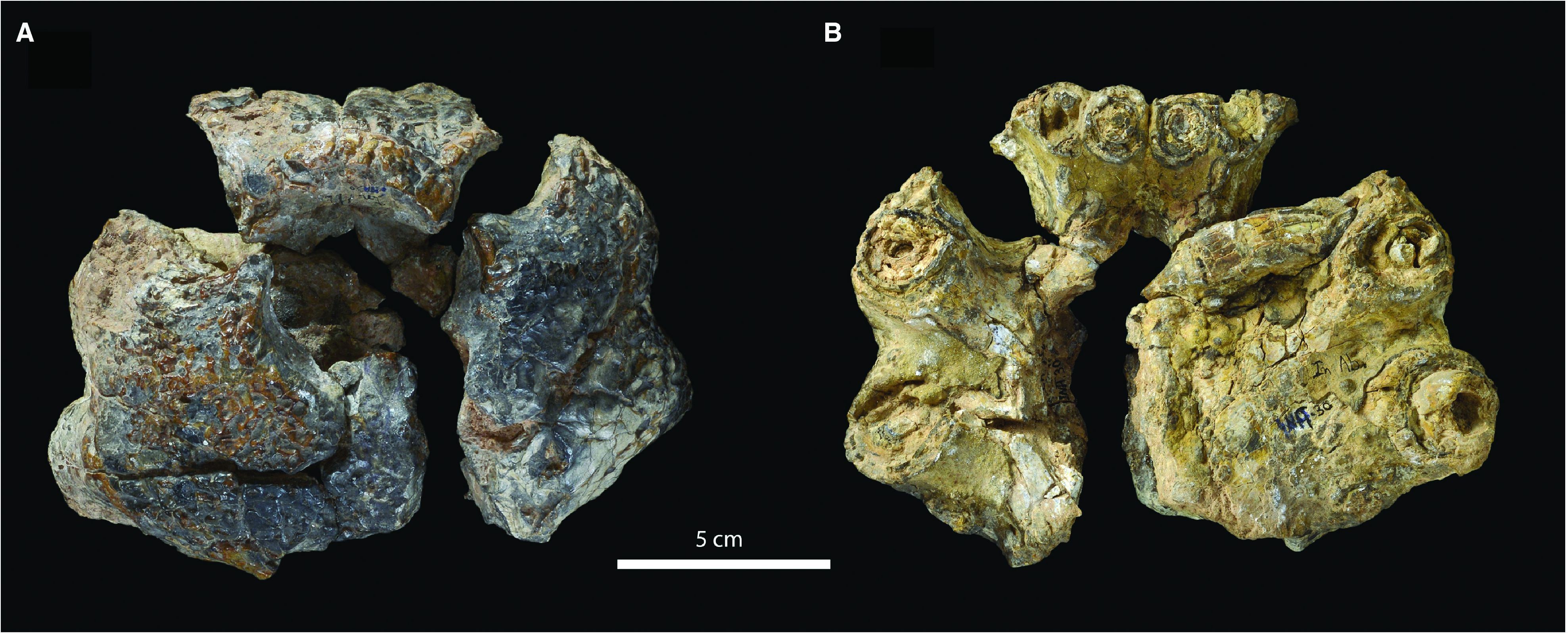

Specimen

MNHN.F INA 30, an incomplete and broken premaxilla.

Locality

West of In Abangharit, Agadez District, Niger.

Horizon and age

Echkar Formation, Tegama Series. Late Albian (Lower Cretaceous) to early Cenomanian (Upper Cretaceous).

Description

The lateral surfaces of MNHN.F INA 30 are convex, whereas the anterior margin is more vertically oriented. There is a raised rim around the external nares, which is most prominent at the anterior margin of the narial opening ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). Along this anterior margin there is no dorsal projection, although this could be because of the presence of the raised narial rim. The loss of this projection is considered to be a defining characteristic of Pholidosauridae ( Fortier et al., 2011) , with the premaxilla anterior to the external nares being convex in most pholidosaurids (e.g. Mook, 1934; Wu et al., 2001; Hua et al., 2007; Lepage et al., 2008; Fortier et al., 2011); however, a dorsal projection is present on the most well-preserved specimen of E. cherifiensis (MNHN.F SAM 129) and in well-preserved isolated premaxillae (MNHN.F MRS 334). Therefore, this characteristic may define a subset of pholidosaurids, rather than an unambiguous apomorphy of the clade.

Ornamentation on the dorsal surface of MNHN.F INA 30 is composed of numerous irregularly distributed pits that vary in size and shape. On the lateral and anterior surfaces of the premaxilla, the ornamentation becomes less pitted with a more irregular array of grooves and raised ridges. The posterior margins of the premaxillae are not preserved, and both posterior processes are missing. Thus we cannot determine the nature of the premaxilla – maxilla contact or the premaxillary constriction (i.e. the narrowing of the premaxilla immediately posterior to the point of maximum width). Moreover, because of the fragmentary nature of the premaxillae, and the post-mortem surface damage it experienced, the medial (i.e. non-alveolar) palatal surfaces are poorly preserved.

Fortunately, the dorsal and lateral surfaces are better preserved. There is an undivided, dorsallyfacing external naris ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). As a result of imperfect preservation, it is hard to discern how extensive the fossa within the narial opening would have been. Moreover, because of the fragmentary nature of the premaxilla we cannot ascertain the former in vivo shape, although it is likely to be very similar to that of E. cherifiensis ( de Lapparent de Broin, 2002) . The posteromedial section of the narial margin is not preserved, and the preserved premaxillary fragments do not fully contact one another along the midline posterior to the external nares. Thus, it is likely that MNHN.F INA 30 shared the same condition as E. cherifiensis ( de Lapparent de Broin, 2002; MNHN.F SAM 129), that the anterior processes of the nasals prevented the premaxillae from suturing along the rostral midline, and that the nasals contributed to the posterior margin of the external nares. The maximal width of the premaxilla of MNHN.F INA 30 was mostly level with the P3 and P4 alveoli, as in E. cherifiensis ( de Lapparent de Broin, 2002; MNHN.F SAM 129).

The right premaxilla bears five alveoli, whereas the fifth alveolus is not preserved in the left premaxilla ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). This matches the premaxillary tooth count of five seen in specimens referred to E. cherifiensis (not four as stated by de Lapparent de Broin, 2002). The first two alveoli (P1 and P2) of both premaxillae are aligned in the same coronal plane, and are oriented vertically and slightly posteriorly. The first two alveoli of both premaxillae form a row of four small and tightly spaced alveoli. These would have created the premaxillary overhang of the dentary seen in other pholidosaurids (e.g. Mook, 1933, 1934; Sereno et al., 2001; Wu et al., 2001; Hua et al., 2007; Lepage et al., 2008; Fortier et al., 2011; Martin et al., 2014). The shape, and how many premaxillary alveoli contribute to this overhang, vary amongst pholidosaurids and are potentially phylogenetically informative.

The P3 and P4 alveoli are separated from P1 and P2 alveoli by large foramina, just as in the specimens referred to E. cherifiensis (MNHN.F SAM 129 and MRS 334; NHMUK PV R 36828; de Lapparent de Broin, 2002). These large, paired foramina appear to be for the reception of the enlarged first dentary tooth crowns. Similar notches (or in some cases just depressions) are also present on the palatal surface of the premaxillae of other pholidosaurids (e.g. Mook, 1933; Sereno et al., 2001; Lepage et al., 2008; Fortier et al., 2011); however, in Meridiosaurus , Oceanosuchus , Sarcosuchus , and Terminonaris these notches are posterior to the P1 and P2 alveoli (or just the P2 alveoli), and are ventral to the external nares ( Mook, 1933; Sereno et al., 2001; Lepage et al., 2008; Fortier et al., 2011). The position and very large size of these foraminae, and the separation of the premaxillary alveoli into distinct units, are autapomorphies of Elosuchus .

As with E. cherifiensis , the P3 and P4 alveoli of MNHN.F INA 30 are considerably larger than the P1 and P2 alveoli, and are in approximately the same sagittal plane. The P3 and P4 alveoli are widely separated from one another, with a deep interalveolar space created by their high alveolar rims. The left premaxilla preserves the P5 alveolus posteromedial to the P4 alveolus. There is no deep interalveolar space between these alveoli, and the gap between the P4 and P5 alveoli is proportionally smaller than the P3 – P4 interalveolar space. The P5 alveolus is smaller than the P1 – P4 alveoli. Also, it is oriented posteriorly. The posteriorly oriented P5 and its posteromedial position relative to the P4 alveolus (rather than posterolateral) are characteristics that MNHN.F INA 30 shares with E. cherifiensis (MNHN.F SAM 129; de Lapparent de Broin, 2002). The P5 alveoli of most other pholidosaurids are posterolateral to the P4 alveoli (e.g. Mook, 1934; Sereno et al., 2001; Wu et al., 2001; Hua et al., 2007; Lepage et al., 2008; Fortier et al., 2011); however, the P5 alveoli of Chalawan thailandicus ( Martin et al., 2014) are also in a posteromedial position. Thus, contra Fortier et al. (2011), the posterolateral position of the fifth premaxillary tooth is not an unambiguous synapomorphy of a monophyletic Pholidosauridae , although the medial ‘migration’ of these alveoli could be a shared characteristic of a more inclusive clade within pholidosaurids.

TETHYSUCHIA BUFFETAUT, 1982 (SENSU ANDRADE ET AL., 2011) FORTIGNATHUS GEN. NOV. http://ZOOBANK.ORG/URN:LSID:ZOOBANK.ORG: ACT: 0F0CCD3A-2831-40DA- A05C- E29E30524889

Type species

Elosuchus felixi de Lapparent de Broin, 2002 (following recommendation 67B of the ICZN code). Now

referred to as Fortignathus felixi ( de Lapparent de Broin, 2002) comb. nov.

Etymology

‘Strong jaws’. Derived from the Latin for strong or powerful (fortis) and the Latinized form of the Greek for jaws (gnathus). Named for the robustness of MNHN.F INA 21 (a referred specimen from a very large individual).

Diagnosis

Same as the only known species (monotypic genus).

FORTIGNATHUS FELIXI ( DE LAPPARENT DE BROIN,

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Elosuchus

| Young, Mark T., Hastings, Alexander K., Allain, Ronan & Smith, Thomas J. 2017 |

Elosuchus felixi

| de Lapparent de Broin F 2002: 283 |