Thalassocaris crinita ( Dana, 1852 )

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5342666 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/0394F723-FF8D-A43C-FC15-F8F0FDB1FAF1 |

|

treatment provided by |

Diego |

|

scientific name |

Thalassocaris crinita ( Dana, 1852 ) |

| status |

|

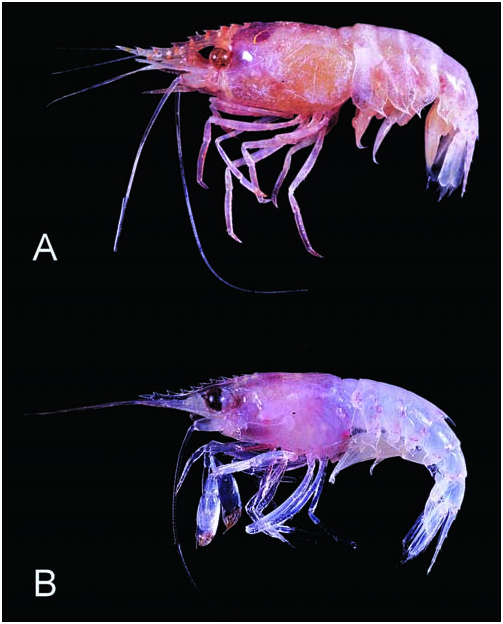

Thalassocaris crinita ( Dana, 1852)

( Fig. 1B View Fig )

Material examined. – Stn. B 2, Panglao Is., Alona reef, 9°33.0'N 123°46.5'E, 5 m, 31 May 2004, 1 ovig. female 4.2 mm ( MNHN) GoogleMaps ; Stn. B 4, Panglao Is., BBC Point, 9°33.2'N 123°48.3'E, 24 m, 1 Jun.2004, 1 ovig. female 4.9 mm, 1 female 3.7 mm, 2 juveniles 2.2 & 2.6 mm ( NTOU) GoogleMaps , 1 female 4.5 mm ( OUMNH) ; Stn. B 16, Panglao Is., Bingag , 9°37.6'N 123°47.3'E, 20 m, 17 Jun.2004, 1 ovig. female 4.1 mm, 1 female 2.9 mm ( NTOU) GoogleMaps ; Stn. B 17, Panglao Is., Bingag , 9°37.5'N 123°46.9'E, 3–21 m, 19 Jun.2004, 2 males 3.3 & 3.8 mm ( MNHN) GoogleMaps ; Stn. B 35, Panglao Is., north of Doljo , 9°35.9'N 123°44.5'E, 31 m, 1 Jul.2004, 1 male 4.1 mm ( OUMNH) GoogleMaps ; Stn. B 42, Panglao Is., between Momo and Napaling , 9°37.0'N 123°46.0'E, 30–33 m, 6 Jul.2004, 1 female 2.2 mm ( NTOU) GoogleMaps ; Stn. L 40, Panglao Is., Tangnan, 9°37.3'N 123°46.5'E, 100–120 m, 24 Jun.2004, 1 male 5.0 mm, 2 females 3.8 & 4.5 mm, 2 juveniles 2.2 & 2.6 mm ( NTOU) GoogleMaps ; Stn. L 46, Balicasag Is., 9°30.9'N 123°41.2'E, 90–110 m, 4 Jul.2004, 1 female 4.9 mm ( NTOU) GoogleMaps ; Stn. L 47, Bohol Is., Cortes Takor , 9°41.3'N 123°49.2'E, ca. 100 m, 5 Jul.2004, 1 female 5.35 mm ( NTOU) GoogleMaps ; Stn. T 11, Bohol Is., Maribohoc Bay , 9°40.9'N 123°50.0'E, 78–95 m, 16 Jun.2004, 1 ovig. female 5.6 mm ( OUMNH) GoogleMaps ; locality not specified, 6 Jul.2004, 1 male 6.6 mm ( NTOU) .

Remarks. – The specimens agree closely with previous descriptions (Gopalo Menon & Williamson, 1971; Chace, 1985), but as already remarked upon by Chace (1985), the species is somewhat variable with regard to the basal portion of the rostrum and the crenulation on the merus of the second pereiopod. In the majority of the present material, the merus is crenulated, although to a varying degree. Variation in the basal portion of the rostrum was most noticeable in juveniles, where it is far less wide, and more parallel sided. Variation in rostral dentition was relatively minor, being 1+7–9/2–3, with in the majority of specimens the post-orbital tooth being reduced to a tubercle only. This species has a wide distribution in the Indo-Pacific ( Hanamura, 1987).

Colouration. – Body generally translucent and covered with minute red dots ( Fig. 1B View Fig ). Eyes dark brown. Eggs yellowish green.

Habitat. – The majority of specimens were obtained by brushing coral and other reef substrates in depths between 5 and 33 m, whilst several others were obtained by the lumum lumun method in depths of 90–110 m (a method which involves submerging nets on the sea floor for about one month) and trawling. This appears to be in contradiction with previous notions on the ecology of this species, as members of the family are generally believed to be pelagic in nature (Gopalo Menon & Williamson, 1971; Poupin, 1998). Indeed, Chace (1985) stated “… usually on continental or insular shelves over depths of less than 100 m ”, although Bruce (1984) considers the species common in coral colonies during the day and common in plankton catches off reefs at night. One of the authors noticed this discrepancy before ( De Grave, 2001), when abundant material was obtained from breaking apart shallow water rubble in northern Papua New Guinea.

In order to investigate this further, we here review all previous records of the habitat of this species. The majority of early publications mentioning this species (e.g., Dana, 1852; Balss, 1914; Borradaile, 1915 as T. affinis ) do not mention habitat, merely stating location and/or depth, although the implication is that the specimens were caught on or adjacent to coral reefs in Borradaile (1917), Kemp (1925) and Holthuis (1953). Armstrong (1941) mentions that two male specimens were collected by hand net at the surface, next to a pier and a further specimen by a submerged light in the lagoon. Chace (1955) discusses specimens collected from 30–33 fathoms on a coral bottom, but does not specify the collecting method. One notable exception is De Man (1920) in which detailed substrate information is given for the Indonesian specimens collected during the Siboga expedition. Most specimens were obtained by dredge from shallow water ( 12–54 m) on either mixed or Lithothamnion bottoms, with three male specimens obtained from surface plankton. One male and 14 juveniles were taken by plankton net in water of 95 m depth at a single station in the Indian Ocean by Gopalo Menon & Williamson (1971), although larvae reported in this study were more common and widespread in the Indian Ocean, mostly in water less than 100 m. Further, Indonesian and Philippine specimens recorded by Chace (1985) were obtained by plankton net, either with the ship at anchor or over shallow water ( 9–18 m). In northern Papua New Guinea, De Grave (2001) collected numerous specimens from shallow ( 5–45 m) coral rubble and living coral colonies, with a single female was collected from a 30–35 m deep light trap. Li & Komai (2003) recorded a single specimen collected by trawl on a muddy sand bottom ( 54 m) in the South China Sea, whilst De Grave & Moosa (2004) recorded the species from 10 m deep rubble samples in Sulawesi. The two most recent records are by Li (2006) who recorded a specimen from a 36 m deep coral reef in the Nansha Islands, collected by grab sampler, and Hayashi (2007) who recorded a specimen from off Kyushu, Japan, collected by Bou-uke-ami net (a pelagic fishing method) at night.

In summary, it thus appears that the overwhelming majority of specimens recorded in the taxonomic literature, which have some level of habitat data, were collected from shallow water, directly on or from the actual substrate, usually coral reef rubble and similar habitats. Therefore, the common assumption that T. crinita is a bathypelagic ( Poupin, 1998) or pelagic ( Chace, 1985) species appears unwarranted, and the species should be considered as inhabiting shallow water, reefal environments. Nevertheless there are some records of planktonic catches, most of which are from very shallow water adjacent to reefs. Hidaka et al. (2003) and Karuppasamy et al. (2006) do record abundant nocturnal catches of the species with plankton nets in waters between 0–200 m deep south of Japan and in the eastern Arabian Sea respectively. It thus follows that, periodically at least, some individuals must leave their diurnal refuges and swim freely in the surrounding waters at night (as already discussed by Bruce, 1984). This ecological assumption would be consistent with the species (and presumably all members of the family) harbouring photophores ( Kemp, 1925; Herring & Barnes, 1976), a rather unusual morphological trait, normally associated with deep-sea, pelagic shrimp species. Interestingly, in the eastern Arabian Sea, Karuppasamy et al. (2006) record a swarm with a density of 302 individuals per 1,000 m 3 in December ( 75 m water depth), but only 28 individuals in May ( 50 m water depth). This observation may indicate a reproductive role of this behaviour, one which is perhaps seasonally structured.

It seems that the only truly planktonic records of adults and juveniles are the specimens collected as part of the International Indian Ocean Expedition, mentioned in Gopalo Menon & Williamson (1971) in water of 95 m depth, as well as the recently recorded specimens in Hidaka et al. (2003) and Karuppasamy et al. (2006). This makes it rather unclear where the previously held assumption by taxonomists of T. crinita being a pelagic species derives from.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |