Arachnopsita uncinata Desutter-Grandcolas, 1997

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.5094.3.3 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:50F1BC50-CEAA-491A-8E72-15F3E545BC49 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6302421 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/0390C840-FFFD-AA62-CCAD-1BFDFE4AFDC5 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Arachnopsita uncinata Desutter-Grandcolas, 1997 |

| status |

|

Arachnopsita uncinata Desutter-Grandcolas, 1997 View in CoL

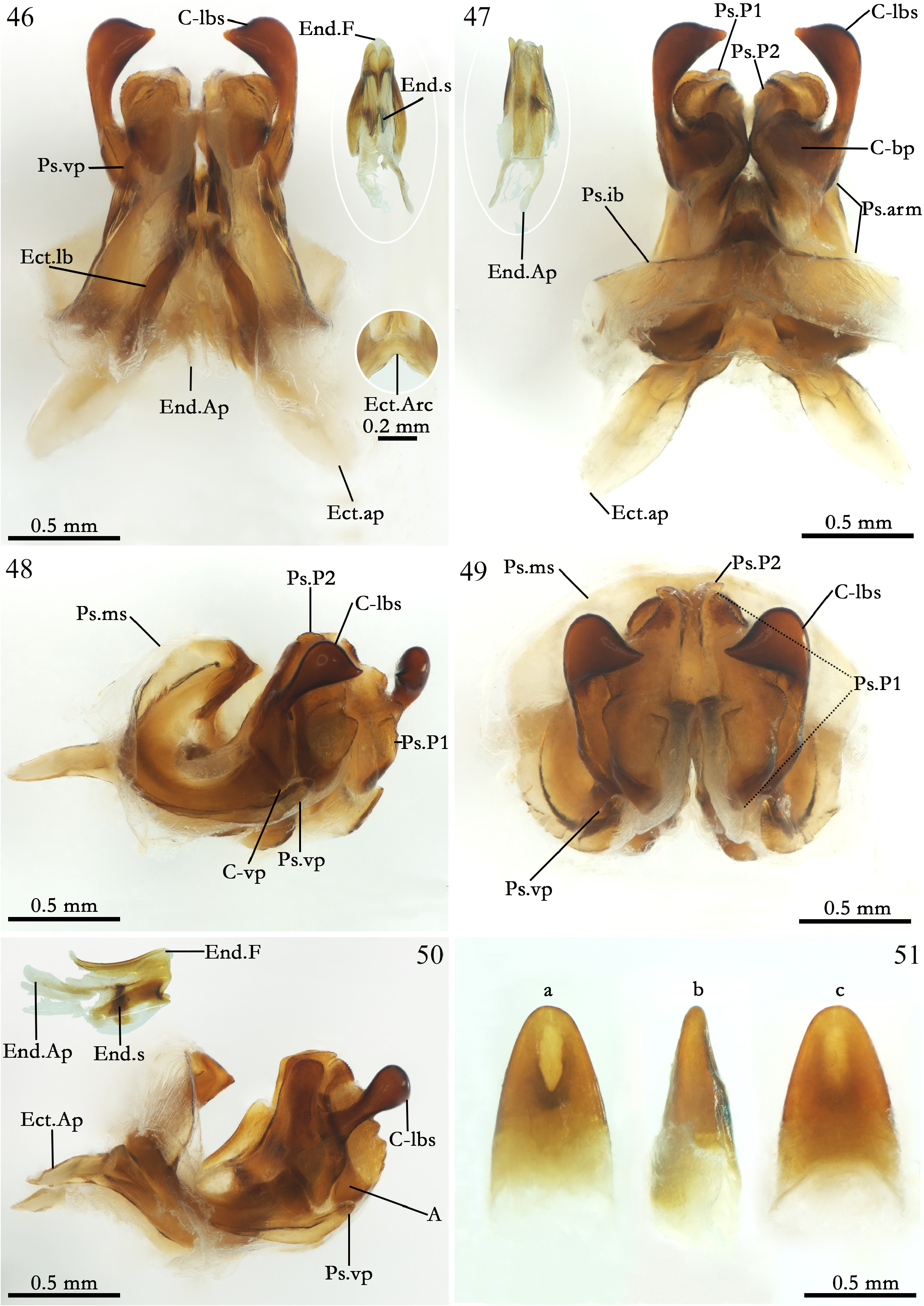

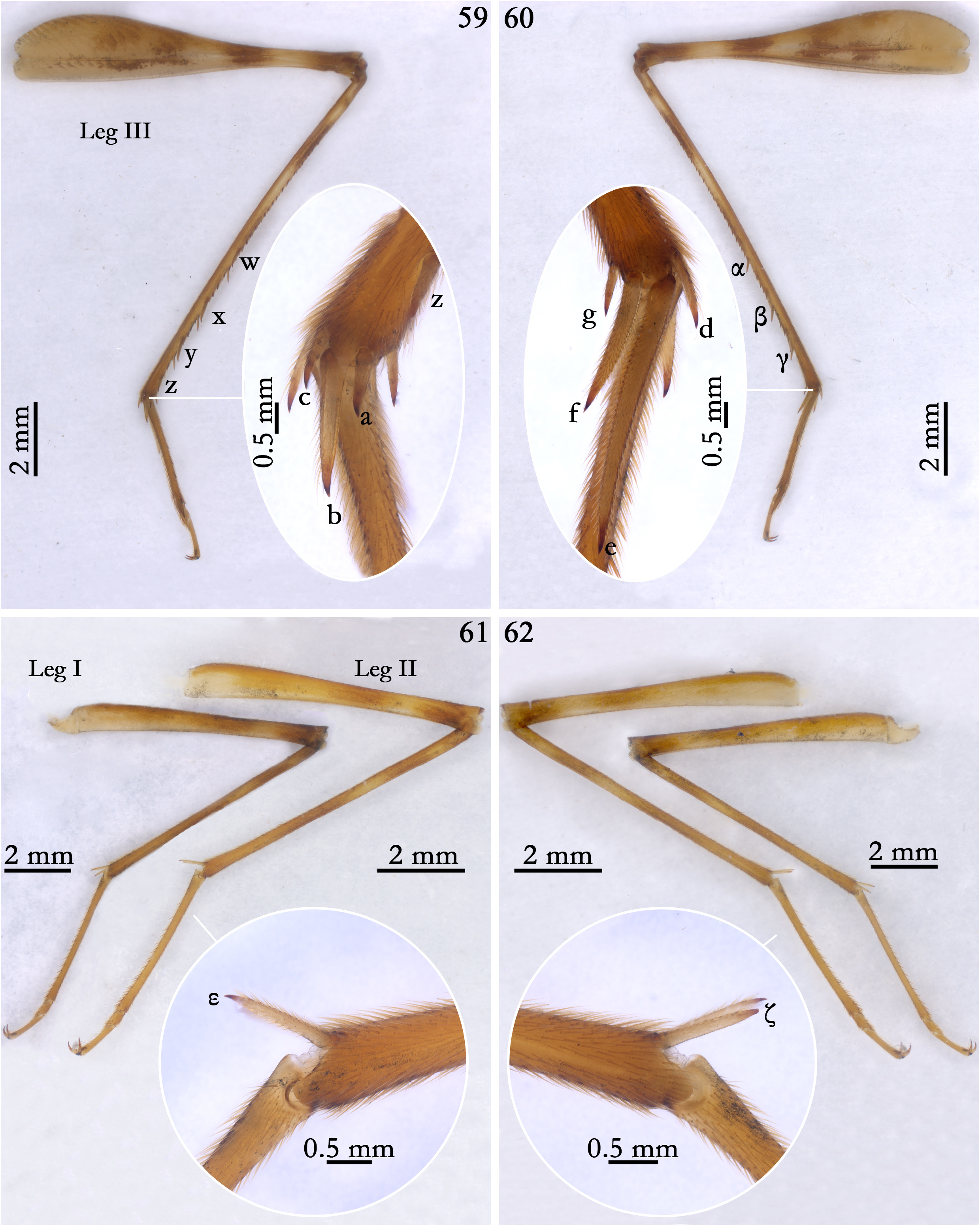

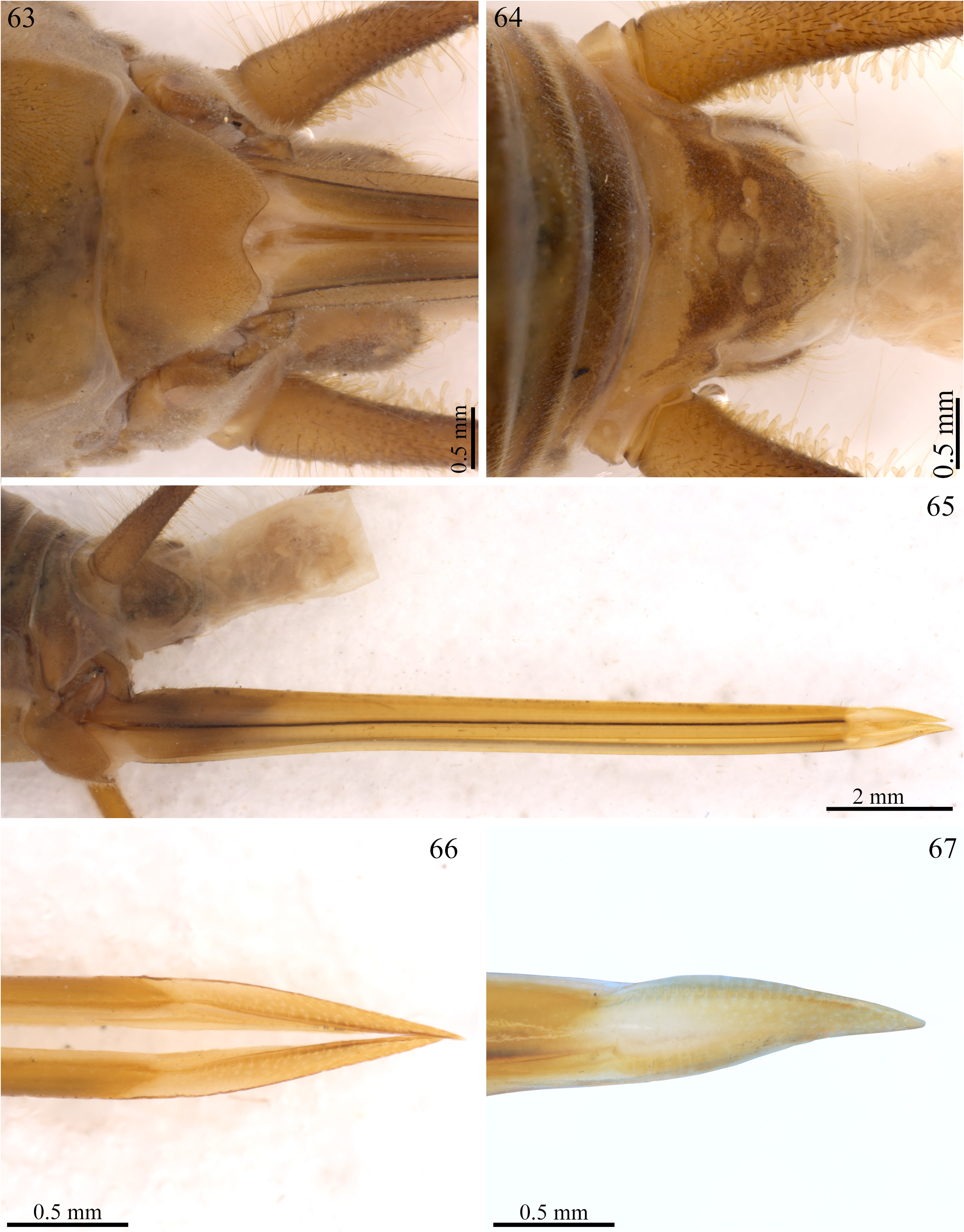

( Figures 46–51 View FIGURES 46–51 , 52–58 View FIGURES 52–58 , 59–62 View FIGURES 59–62 , 63–67 View FIGURES 63–67 , Table 3 View TABLE 3 )

Material examined. Near of type locality, 3 ♂♂ (ISLA 12434; 12436; 12437) and 1 ♀♀ ( ISLA 12435), Guatemala, Alta Verapaz, municipality of Lanquín, Cueva Coral (15°33’27.7” N; 89°57’48.7” W), 22.vi.2017, Pacheco, G. S. M., leg GoogleMaps ..

Additional description, male ♂ ( ISLA 12434), near of type locality (Cueva Coral). Body color: dorsal head, pronotum and abdomen light yellowish brown with some small dark spots (different than A. maya n. sp. and A. cavicola which do not show evident stains), grayish brown ventrally ( Figs 54 and 55 View FIGURES 52–58 ); legs light yellowish brown with dark spots at the femur and tibia, slightly whitish at its proximal portion ( Figs 59–62 View FIGURES 59–62 ); cerci uniformly brown ( Fig. 56 View FIGURES 52–58 ). Head: slightly pubescent and with the long bristles at base of vertex (some which were lost probably in fixation), elongated at frontal view (3.938 and 2.937 mm, length and width respectively) ( Figs 52 and 53 View FIGURES 52–58 ); fastigium extending the vertex in an inclined plane ( Fig. 54 View FIGURES 52–58 ); gena with a darkened strip connecting the compound eyes to the mandible insertion (more pronounced compared to A. maya n. sp. and A. cavicola ), front light yellowish brown, clypeus and labrum whitish brown, mandibles yellowish brown and sclerotized at the apex ( Figs 52–54 View FIGURES 52–58 ); all maxillary palpomeres pubescent and yellowish brown, first two short and same size, last three are bigger and similar size, fifth palpomere claviform, arched and whitish at the tip ( Figs 52 and 53 View FIGURES 52–58 ), all labial palpomeres pubescent and light yellowish brown, increasing in size, third palpomere claviform ( Figs 52 and 53 View FIGURES 52–58 ); scape whitish at the base and dark yellowish brown next to the pedicel, pedicel dark yellowish brown, antennomeres uniformly dark yellowish brown ( Figs 52–54 View FIGURES 52–58 ); compound eyes black and more developed than in A. maya n. sp. and A. cavicola , elongated, border of ommatidia lightly depigmented, ocelli absent ( Figs 52–54 View FIGURES 52–58 ). Thorax: pronotum slightly pubescent, lighter than in A. maya n. sp. and A. cavicola , anterior, medial and posterior portion with less sclerotized regions (appearance of whitish spots) and dark spots distributed along the sagittal axis in dorsal and lateral view ( Figs 54 and 55 View FIGURES 52–58 ); dorsal disk broader than long (less long compared to A. maya n. sp. and A. cavicola ), lateral lobes rounded, anterior and posterior margins sub-straight, anterior margin with long bristles, posterior and lateral margins with possibly lost bristles in fixation ( Figs 54 and 55 View FIGURES 52–58 ). Legs. In general, femur, tibia and tarsus pubescent; femur smaller than tibia (μ = 13.736 ± 0.001 mm; μ = 15.153 ± 1.395 mm, femur and tibia respectively, Leg III, n = 2) ( Figs 59–62 View FIGURES 59–62 ). Leg I ( Figs 61 and 62 View FIGURES 59–62 ): tibia armed with two same-sized ventral apical spurs, tympanum absent; first tarsomere ventrally serrated and twice longer than second and third together. Leg II ( Figs 61 and 62 View FIGURES 59–62 ): tibia armed with two same-sized ventral apical spurs ( Fig. 61 View FIGURES 59–62 ; ε and Fig. 62 View FIGURES 59–62 ; ζ); first tarsomere ventrally serrated and twice longer than the second and third together. Leg III: femur dilated; tibia serrulated, armed with four subapical spurs on outer side ( Fig. 59 View FIGURES 59–62 ; w, x, y, z), the distal being smaller ( Fig. 59 View FIGURES 59–62 , z) and three on inner side ( Fig. 60 View FIGURES 59–62 ; α, β, γ), three apical spurs on outer ( Fig. 59 View FIGURES 59–62 ; a, b, c) and four on the inner side ( Fig. 60 View FIGURES 59–62 ; d, e, f, g), the inner being the longest, the apical spur b is more broader than in A. maya n. sp. and A. cavicola ; first tarsomere about twice longer than the second and third together, armed with two apical spurs ( Figs 59 and 60 View FIGURES 59–62 ). Right Tegmen: absent ( Fig. 54 View FIGURES 52–58 ). Abdomen: cerci long and pubescent, mainly in the base ( Fig. 56 View FIGURES 52–58 ); sub-genital plate dark brown, sub-quadrangular, pubescent, distal margin lightly curved inward, with a small central groove, proximal margin slightly wider ( Figs 56 and 57 View FIGURES 52–58 ); supra-anal plate dark brown, with some lighter spots, pubescent, proximal margin lightly V-shaped and with two lateral projections, slightly concave distally in side margins, and with two small distal-lateral globular projections with long bristles ( Figs 56 and 58 View FIGURES 52–58 ).

Male phallic sclerites ( ISLA 12436, Figs 46–50 View FIGURES 46–51 ). Pseudepiphallus: arm short and curved inward ( Fig. 47 View FIGURES 46–51 , Ps.arm); ventral projection reduced and slightly acuminate ( Figs 46, 48–50 View FIGURES 46–51 , Ps.vp); inner bars well sclerotized, curved inward forming a central acuminate projection ( Fig. 47 View FIGURES 46–51 , Ps.ib); membranous shield broad and flat, narrower horizontally compared to A. maya n. sp. and A. cavicola in front view ( Figs 48 and 49 View FIGURES 46–51 , Ps.ms); paramere 1 well developed, dilated with globular and sub-quadrangular projections, with less sclerotized portion in most of its extension, evident in the frontal and diagonal view ( Figs 47–49 View FIGURES 46–51 , Ps.P1); paramere 2 undeveloped, connected to Ps.P1 and same texture less sclerotized than this one, flattened and projecting towards C-sclerite basal plate (C-bp) ( Figs 47–49 View FIGURES 46–51 , Ps.P2); A sclerite well sclerotized, starting from the Ps.arm, broader than in A. maya n. sp. and involving the paramere 1 ( Figs 47 and 50 View FIGURES 46–51 , A). C-sclerite: in general is the most sclerotized part of the sclerite; ventral projection rounded and little developed compared to A. maya n. sp. and A. cavicola ( Fig. 48 View FIGURES 46–51 , C-vp); laterobasal spine well developed, elongated, claviform (similar to a dilated hook), with a spine at apex of the inner face slightly curved internally ( Figs 46–50 View FIGURES 46–51 , C-lbs); basal plate more broad and less elongated compared to A. maya n. sp. and A. cavicola , inclining inward and reaching the Ps.P2 ( Fig. 47 View FIGURES 46–51 , C-bp). Ectophallic invagination: arc developed, upper and lower central part curved up ( Fig. 46 View FIGURES 46–51 , Ect.Arc); lateral bars elongated and projected inwards, more narrow distally compared to A. maya n. sp. and A. cavicola ( Fig. 46 View FIGURES 46–51 , Ect.lb); apodemes developed and dilated, more flatted and less elongated compared to A. maya n. sp. and A. cavicola , projected outwards of the sclerite, at dorsal and ventral view, with its distal portion lightly acuminate at the apex ( Figs 47 and 50 View FIGURES 46–51 , Ect.ap); Endophallus: endophallic fold small and narrow towards the at apex compared to A. maya n. sp. and A. cavicola ( Figs 46 and 50 View FIGURES 46–51 , End.F); sclerotized extension of endophallic fold reduced and horizontally projected ( Figs 46 and 50 View FIGURES 46–51 , End.s); endophallic apodeme little sclerotized, less elongated, more dilated and thin compared to A. maya n. sp. and A. cavicola ( Figs 47 and 50 View FIGURES 46–51 , End. Ap).

Female ( ISLA 12435): same appearance in relation to males, with the same pattern of small dark spots, body size apparently slightly bigger than male (♀ 20.748 mm); apterous; femur always smaller than tibia; sub-genital plate brown and pubescent, short, V-shaped, distal margin forked ( Fig. 63 View FIGURES 63–67 ); supra-anal plate brown whitish with whitish spots and pubescent, distal margin rounded with long bristles, proximal with two small lightly pointed projections ( Fig. 64 View FIGURES 63–67 ); ovipositor yellowish brown and elongated, sword shaped, with a constriction near the apex, pointed apex ( Figs 65–67 View FIGURES 63–67 ). Female genitalia ( ISLA 12435, Fig. 51 View FIGURES 46–51 ). Copulatory papilla elongated and cone shaped, narrowing ventraly, dorsally and lateral margins towards at apex ( Fig. 51 View FIGURES 46–51 , a-c); with an oval opening near the apex at ventral view ( Fig. 51 View FIGURES 46–51 , a).

Ecological Remarks: Individuals of both Arachnopsita cavicola ( Fig. 72 View FIGURES 68–73 ) and A. uncinata ( Fig. 73 View FIGURES 68–73 ) were observed in some caves in the Lanquín region, exibiting simpatric populations in at least two caves (Gruta de Lanquín and Cueva Chipix caves). In the Cueva Coral cave, only specimens of A. uncinata were found. Individuals of both species were only observed in aphotic areas of the caves, but not necessarily far from entrances. They were mostly observed walking on speleothems, usually on the cave´s walls. The organic resources occurring in those caves were bat guano, which, in some cases, was represented by huge deposits (as in the innermost part of the Gruta de Lanquín cave), and vegetal debris brought by streams (as the case of the Cueva Chipix cave) ( Pacheco et al. 2020). It is interesting noting that the population densities of both species are quite reduced, contrarily to what is usually observed for many key cave cricket species ( Lavoie et al. 2007). Individuals of both species were randomly observed inside the caves, and no aggregation was observed in any cave. Furthermore, there seems not to occur any segregation among the species populations within the cave, both occurring in simpatry. Curiously, even in the big bat guano pile located in the Gruta de Lanquin cave, only few specimens were found, contrasting with hundreds of cockroaches and millipedes. In the Cueva Chipix cave, only few bat guano piles were observed, and the main organic resource occurring in the cave was vegetal debris brought by the stream which sinks in the cave. Hence, it seems that both species are opportunistic feeders, foraging any available organic debris occurring in caves. The main predator of both cricket species, which were observed in all caves in the region, was the phrynid amblypygid Paraphrynus williamsii Moreno, 1940 .

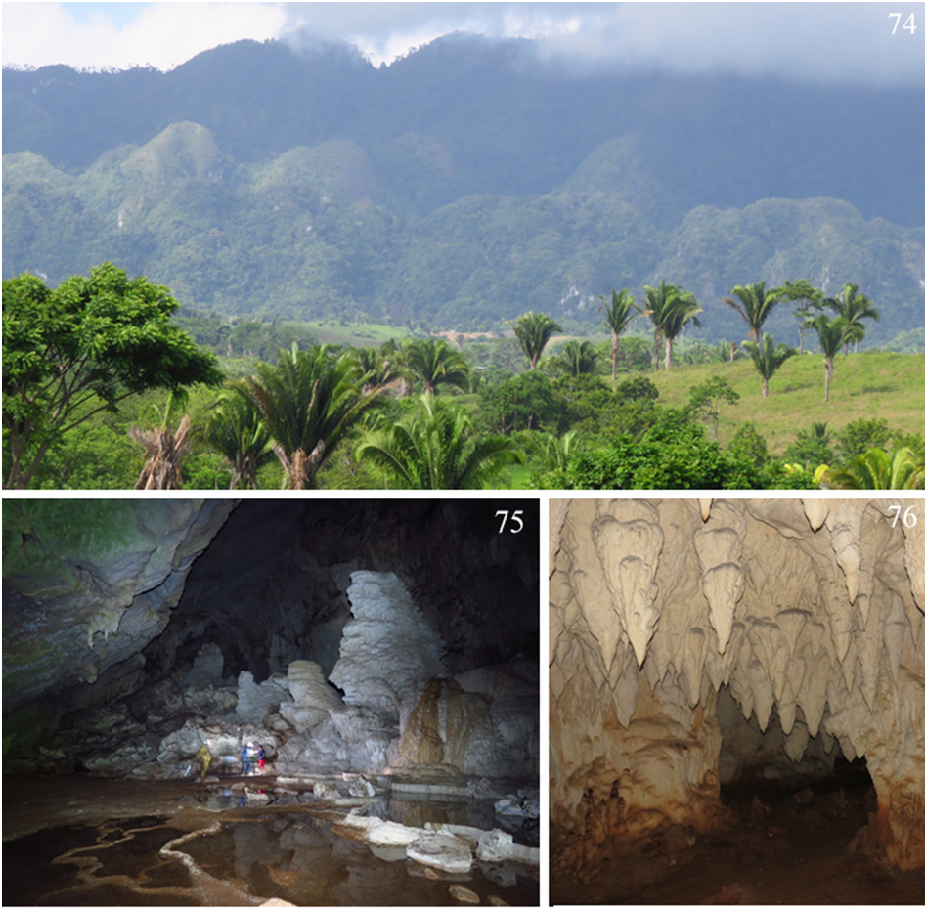

The Lanquin region represents one of the most important tourist destinations in Guatemala, presenting some astonishing landscapes ( Figs 68 and 69 View FIGURES 68–73 ). Among the touristic destinations, the caves are highly sought after. The region presents a national park created in 1955 (Grutas de Lanquín National Park) which receives a large number of visitors during the whole year ( Dreux 1974; Dudeck 2000). This park virtually covers only the external immediate surroundings of the Gruta de Lanquín cave ( Figs 70 and 71 View FIGURES 68–73 ), which is highly explored touristically, albeit without presenting almost any control of the touristic influx inside the cave ( Pacheco et al. 2020). Despite the uncontrolled tourism in the Gruta de Lanquín cave, both species seem not to be threatened, since only part of the cave is used for touristic purposes. Furthermore, both species were recorded in other caves, and considering that there are dozens of caves in the area, populations are probably widespread. However, it is important to highlight that agriculture might represent a concern, since several areas were deforested for crops, some of them in the surroundings of caves ( Fig. 74 View FIGURES 74–76 ). Considering that both species are troglophilic, it is likely that external populations do exist, that may act connecting cave populations. Thus, it is advisable to both protect some caves as their surroundings, especially those presenting bigger populations.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

SuperFamily |

Grylloidea |

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |