Pteronura brasiliensis, Zimmermann, 1780

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5714044 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5714103 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/038F87D4-CA46-FFA9-CAE9-3DF2F7AEFDBC |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Pteronura brasiliensis |

| status |

|

Giant Otter

Pteronura brasiliensis View in CoL

French: Loutre géante / German: Riesenotter / Spanish: Nutria gigante

Taxonomy. Mustela brasiliensis Gmelin, 1788 View in CoL ,

Brazil.

Monotypic.

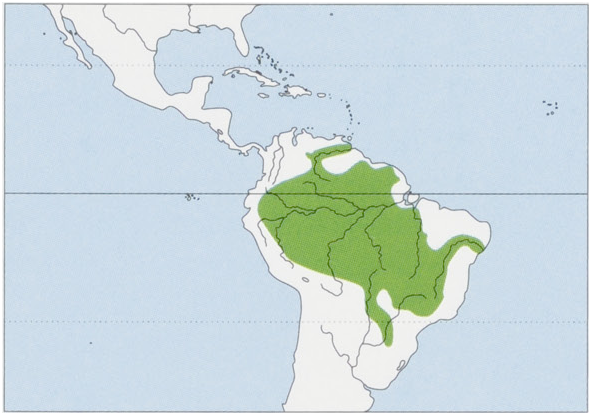

Distribution. Amazon and Orinoco basins from Venezuela to Paraguay and S Brazil. Formerly also Argentina and Uruguay, but now may be extinct there. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 100-130 cm (males), 100-120 cm (females), tail 45-65 cm; weight 26-32 kg (males), 22-26 kg (females), adult males are slightly larger than females. The Giant Otter is the largest South American otter. It has a broad and flattened head and large eyes. The pelage is reddish to dark brown or almost black. There are large and distinctive white to yellow markings on the upper chest, neck, throat, and lips that contrast sharply with the darker body; these patches may unite to form a large “bib”. The rhinarium is fully haired. Thetail is large and flattened dorsoventrally. All the feet are fully webbed. The skull is massive and flat.

Habitat. Giant Otters are found in slow-moving rivers and creeks within forests, swamps, and marshes. They also occur in lakes, reservoirs, and agricultural canals. Although Giant Otters may inhabit dark or murky water, they prefer clear water and waterways with gently sloping banks and good cover.

Food and Feeding. Primarily fish eaters; adults consume an estimated 3 kg offish daily. The main fish species eaten are from the suborder Characoidei and are 10-60 cm in length. Other prey items are rare, but may include crabs, small mammals, amphibians, birds, and molluscs. There are records of Giant Otters eating large prey such as anacondas and other snakes, black caimans, and turtles. On the Jauaperi River in the central Brazilian Amazon, remains of fish were found in all spraints. The main fish groups were Perciformes ( Cichlidae , 97-3%), Characiformes (86-5%) and Siluriformes (5-4%). The Characiformes were represented mainly by Erythrinidae ( Hoplias sp. 90-6%), followed by Serrasalmidae (28%). The Anostomidae occurred with a frequency of 18:7%. On the Aquidauana River, the Characiformes were the most frequent fish group, represented in 100% of all samples, followed by Siluriformes (66-6%) and Perciformes (33:3%). Prey is caught with the mouth and held in the forepaws while being consumed. Small fish may be eaten in the water, but larger prey are taken to shore.

Activity patterns. Diurnal. Giant Otters frequently go ashore to groom, play or defecate. Rest sites are in burrows, under root systems, or under fallen trees. At certain points along a stream, areas of about 50 m * are cleared and used for resting and grooming. Dens may consist of one or more short tunnels that lead to a chamber about 1-2- 1-8 m wide. Nine vocalizations have been distinguished including screams of excitement and coos, given upon close intra-specific contact.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Giant Otters are excellent swimmers and seem clumsy on land; however, they are capable of moving considerable distances between waterways. Daily travel may reach 17 km. During the dry season, when the young are being reared, activity is generally restricted to one portion of a waterway. In the wet season, movements are far more extensive. Giant Otters live in family groups that consist of a mated adult pair, one or more subadults, and one or more young of the year. These groups may reach 20 individuals, but are usually four to eight. Solitary animals also occur as transients. Home ranges are 12-32 linear km of creeks or rivers, or 20 km? of lakes or reservoirs. The core area of the home range is defended actively by family members; this core area encompasses 2-10 km of creek or 5 km ” of lake. Both sexes regularly patrol and mark their territory; groups tend to avoid each other and fighting appears to be rare.

Breeding. The young are apparently born at the start of the dry season, from August to early October, although births may also occur from December to April. Gestation is 65-70 days, although evidence of delayed implantation of the fertilized eggs into the uterus has been observed in captivity. Litter size is up to five, usually one to three. Neonates weigh c. 200 g and measure c. 33 cm. They are able to eat solid food by three to four months and weaning occurs after nine months. The young remain with the parents until the birth of the next litter and probably for some time afterward. Adult size is reached after ten months and sexual maturity is attained at about two years.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Endangered in The IUCN Red List. The Giant Otter is protected throughoutits distribution.The current total wild population is estimated at between 1000 and 5000 individuals. Major threats are habitat degradation, water pollution, and the ever-increasing encroachment of humans on their habitats, which may lead to a potential future reduction in population size of around 50% over the next 20 years. Other threats for this species are the continued illegal killing for their skins or meat, captures for the zoo trade, or robbing of dens for cubs to be sold as pets. There are also conflicts with fishermen as otters are perceived to reduce available fish stock, although studies have shown little overlap in otter prey species and those of commercial interest. Canine diseases that are transferred through domestic livestock, such as parvovirus and distemper, are also a threat.

Bibliography. Autuori & Deutsch (1977), Brecht-Munn & Munn (1988), Carter & Rosas (1997), Chebez (2008), Corredor & Tigreros (2006), Defler (1986b), Duplaix (1980), IUCN (2008), Laidler & Laidler (1983), Parera (1992), Rosas et al. (1999), Van Zyll de Jong (1972), Wozencraft (2005).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.