Solanum carolinense var. carolinense, L. VAR. CAROLINENSE

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1600/036364415x689302 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6339066 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03815163-145D-0605-8481-81800D2A1FE6 |

|

treatment provided by |

Valdenar |

|

scientific name |

Solanum carolinense var. carolinense |

| status |

|

2a. SOLANUM CAROLINENSE L. VAR. CAROLINENSE View in CoL View at ENA

Solanum carolinense var. pohlianum Dunal, Prodr. View in CoL 13(1): 305. 1852.— TYPE: BRAZIL. Without precise locality, s.d. (fr), J. B. E. Pohl s. n. ( lectotype, designated here: M– M0171734 [scan!]) .

Solanum pleei Dunal, Prodr. View in CoL 13(1): 305. 1852.— TYPE: U. S. A. Am[erica] septentrionale, s.d. (fl, fr), A. Plée 204 ( holotype: P–P00325315!; isotype: MPU–MPU022909 [scan!]).

Solanum carolinense var. albiflorum Kuntze, Revis. Gen. Pl. View in CoL 2: 454. 1891.— TYPE: U. S. A. Missouri: St. Louis, 1 Sep 1874 (fr), C. E. O. Kuntze 2768 ( lectotype, designated here: NY –NY00138948 [scan!]).

Solanum carolinense View in CoL f. albiflorum (Kuntze) Benke, Am. Midl. Nat. 22: 213. 1939. — TYPE: Based on Solanum carolinense var. albiflorum Kuntze.

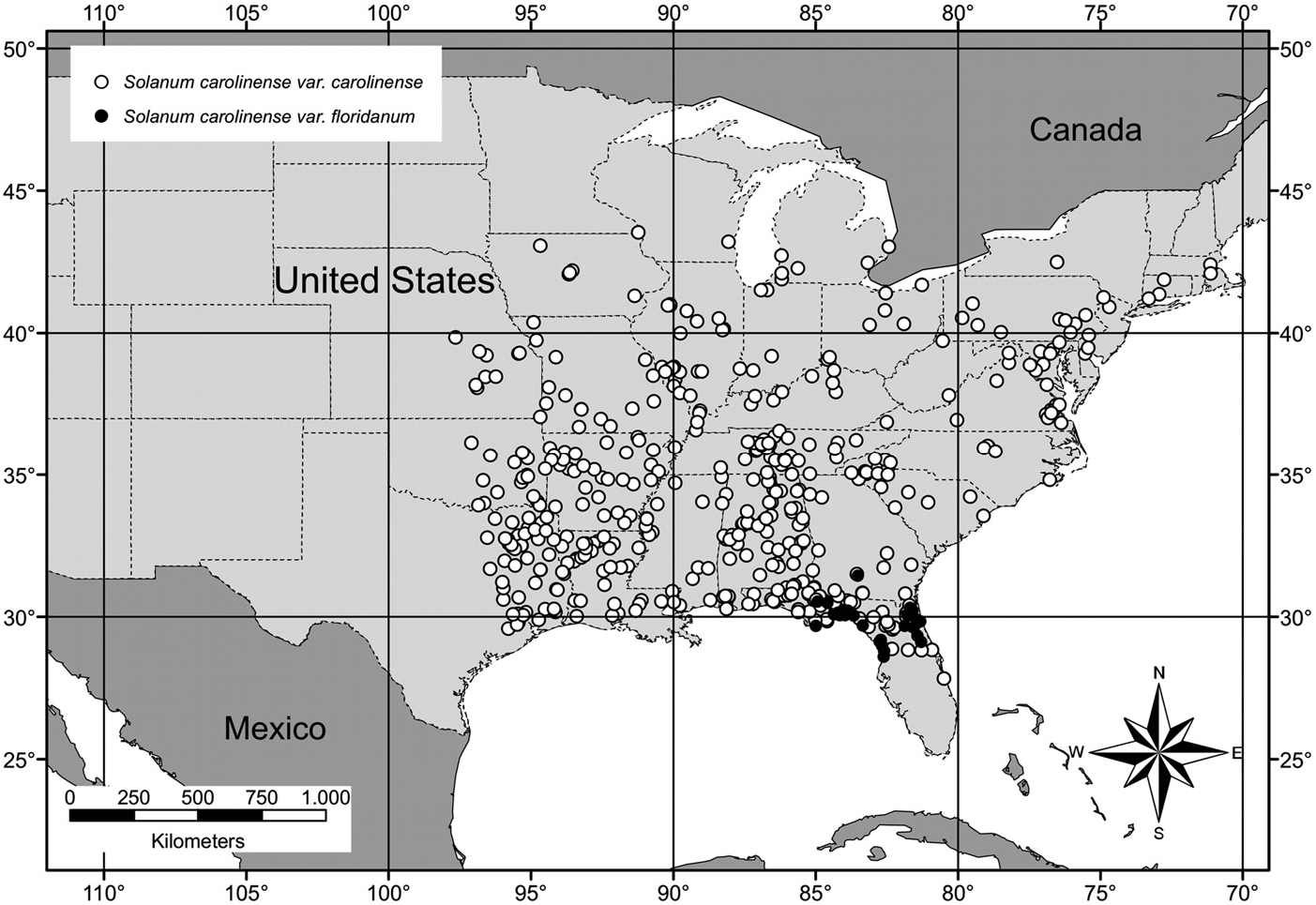

Distribution and Habitat — In the protologue of Solanum carolinense var. carolinense, Linnaeus (1753) writes “ Habitat in Carolina ,” but a more precise geographic origin of the lectotype specimen cannot be determined. While it is likely that it was collected in the southeastern United States in the vicinity of the Carolinas, it is possible that it was collected from a plant grown in Europe from seed collected from North America (S. Knapp, pers. comm.). Furthermore, the native distribution of S. carolinense var. carolinense prior to European settlement in North America is not known with much precision at a local scale because of its weediness and ability to disperse and colonize areas outside of its native range. Based on the location data of ca. 500 herbarium specimens examined for this work, its inferred native distribution extends from central Florida north to New York and Massachusetts and west to Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska to about the 97th meridian west ( Fig. 5 View FIG ). The species reaches Canada only in the southernmost areas

of Ontario and Quebec Provinces ( Bassett and Munro 1986; Cayouette 1972), and except for a single unverified report of the species in Mexico from the states of Sonora, Tamaulipas, and Nuevo Leon ( Eberwein and Litscher 2007), we have not seen any additional evidence suggesting it occurred there as part of its native range. Recent floristic treatments and online databases record occasional occurrences in the western United States ( Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Idaho, Washington, Oregon, and California) where some states have classified the species as a noxious weed (e.g. Arizona, California, and Nevada [ USDA 2014]).

The species has been introduced in many areas around the world and has been reported from Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Canada, China, Croatia, England, France, Georgian Republic, Germany, Haiti, India, Italy, Japan, Moldova, Nepal, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, South Korea, Turkey, and Ukraine ( Cayouette 1972; Trapaidze 1972; D’ Arcy 1974; Gazi-Baskova and Segulja 1978; Izhevskii et al. 1981; Bassett and Munro 1986; Ouren 1987; Webb et al. 1988; Park et al. 2001; Merluzzi et al. 2003; Li et al. 2006; Imaizumi et al. 2006; Eberwein and Litscher 2007; Dirkse et al. 2007; Viggiani 2008; Yasuyuki et al. 2010; Follak and Strauss 2010; Chinnusamy et al. 2011; Klingenhagen et al. 2012; Canadensys 2014).

Solanum carolinense var. pohlianum was described from a Pohl collection that was likely made near the Brazilian port city of Salvador from what was an adventive population established by an accidental introduction to the area (L. Giacomin pers. comm.). There is no evidence that S. carolinense has been collected in Brazil since the time of Pohl’ s collections ( Stehmann et al. 2013). In addition, we have not seen any specimens or reports of the species from other locations in Central or South America or Africa.

In some areas outside of its native range (e.g. China), Solanum carolinense var. carolinense occurs as a harmless exotic species, but in other areas the species is a serious pest (e.g. Italy, Japan). Apparently it is inadvertently dispersed by humans over long distances through shipments of soybeans or livestock fodder that are contaminated with seeds ( Ouren 1987; Park et al. 2001; Follak and Strauss 2010). New introductions to temperate and subtropical regions around the world are expected to continue as long as agricultural crops are exported abroad from the eastern and southeastern United States.

Solanum carolinense var. carolinense grows in a wide variety of conditions, from dry, well drained soils to seasonally inundated swales, fields, and river banks, from deep shade to full sun, and in sands, clays, loams, gravels, serpentine and calcareous outcrops, and the margins of coal mine and dredge spoils. It grows in various plant communities including prairies, deciduous woodlands, swamps, and pine forests, and in disturbed areas such as roadsides, grazed and mowed pastures, ditches, cultivated fields, urban waste areas, and utility and railroad rights of way. It has been collected from cultivated fields of peanuts, wheat, maize, cotton, tomato, potato, alfalfa, green beans, and soybeans. The species grows at elevations from 0–850(–1200) m.

Phenology — In North America, the species flowers between May and October and fruits between June and November.

Conservation Status — The calculations for the extent of occurrence (ca. 3 × 10 6 km 2) and area of occupancy ( 7,328 km 2) for Solanum carolinense var. carolinense were based on its estimated native range in North America ( Fig. 5 View FIG ). Because it is invasive and has the potential to expand its population size when introduced to suitable habitat outside of its native range, it is assigned a preliminary conservation status of “least concern” (LC).

Etymology — The specific epithet means “from the Carolinas” in the United States, the presumed type locality of the species.

Vernacular Names and Uses — Solanum carolinense var. carolinense is widely known as horsenettle or Carolina horsenettle, but several less commonly used names include ball-nettle, bull-nettle, apple-of-Sodom, and sand-brier ( Alex et al. 1980, Muenscher 1951; Bassett and Munro 1986). Given its wide distribution outside of North America, vernacular names in other languages include: morelle de la Caroline (French), ortiga de caballo (Spanish), Carolinsche-Pferdenessel, Carolina-Nachtschatten, and Trostbeere (German), Paardenetel (Dutch), паслён каролинский (Russian), and waru nasubi (Japanese) ( Alex et al. 1980; Eberwein and Litscher 2007).

Some accounts have reported that the dried fruits and roots have been used as a sedative, antispasmodic, diuretic, and aphrodisiac, and that poultices, ointments, and teas made from the fruits or leaves have been used for the treatment of epilepsy, sore throat, toothache, contact dermatitis, worms, and mange in dogs ( Grieve 1974; Foster and Duke 1990; Yasuyuki et al. 2010). However, all parts of the plant are considered to be poisonous, and the glycoalkaloids contained in the mature fruits are known to be toxic to livestock (cattle, sheep) and humans ( Muenscher 1951; Hulbert and Oehme 1963; Hardin and Arena, 1969; Hamilton 1980; Turner and Szczawinski 1991; Wink and Van Wyk 2008). Cipollini and Levey (1997) reported that mature fruits contained 10–30 mg /g dry mass of glycoalkaloids, primarily α- solasonine and α- solamargine. A case of fatal human poisoning was documented in 1963 when a 6-yr-old boy in Pennsylvania died after eating the fruit of S. carolinense var. carolinense ( Kingsbury 1964) .

Chromosome Number — A gametophytic chromosome number of n = 12 was reported by D’ Arcy (1969), Hardin et al. (1972), and Bassett and Munro (1986), and a sporophytic number of 2 n = 24 was reported by Hill (1989).

Ecology — As a weedy species, Solanum carolinense var. carolinense exhibits several attributes that make it a highly competitive and invasive weed: it colonizes early successional or disturbed habitats, produces many seeds per fruit, grows rapidly, reproduces vegetatively, resists mechanical methods of control, has generalized pollinators, and can grow in a variety of biotic and abiotic conditions (e.g. Kolar and Lodge 2001). These same characteristics that contribute to the invasiveness of S. carolinense var. carolinense also make it difficult to control. Human disturbance such as plowing serve to open up new habitat for its dispersal and establishment. It is capable of producing ca. 40–170 seeds per fruit, with a single plant producing up to ca. 5,000 seeds that may be dispersed by birds and mammals ( Martin et al. 1951; Gunn and Gaffney 1974; Solomon and McNaughton 1979; Cipollini and Levey 1997).

As with other weedy species, Solanum carolinense var. carolinense is pollinated by a variety of generalist insects. The flowers are odorless and without nectar, and provide pollen as a reward ( Solomon 1987). In North America, the species has been observed to be buzz pollinated by a variety of non-specialist bees, including sweat bees ( Lasioglossum spp.), bumblebees ( Bombus spp.) carpenter bees ( Xylocopa spp.), and mining bees ( Andrena spp.; Hardin et al. 1972; Quesada-Aguilar et al. 2008).

In its native range and in many introduced areas, Solanum carolinense var. carolinense is extremely difficult to control in cultivated areas and pastures once established. The magnitude of the economic impact to agriculture is difficult to estimate, but given its wide distribution in the United States and locations abroad, the costs associated with control of the species, crop losses, contaminated harvests and fodder, and reduced availability of pastureland are potentially enormous (e.g. Follak and Strauss 2010). In North America, some crop yields have been decreased up to 60% by its presence, and the quality of pastures can be severely diminished ( Gorrell et al. 1981; Hackett et al. 1987; Pimentel et al. 2000).

Control of the species using mechanical methods or single herbicide applications is usually not effective ( Ilnicki et al. 1962; Nichols et al. 1992). Plants that are mowed during the first half of the growing season re-emerge vigorously, and tilling causes vegetative reproduction from root fragments, which often increases the severity of the infestation ( Furrer and Fertig 1960; Takematsu et al. 1979; Gorrell et al. 1981; Wehtje et al. 1987). Intensive herbicide applications with certain mixtures and treatments are somewhat effective (e.g. Whaley and Vangessel 2002; Armel et al. 2003; Beeler et al. 2004), but the use of biological control agents carries considerable risk given the relatively close phylogenetic relationship to other solanaceous crops such as tomato, potato, and eggplant ( Nichols et al. 1992).

In addition to being an aggressive agricultural pest, Solanum carolinense var. carolinense is a host to many insects, fungi, and viruses that can cause damage to a variety of crops, especially solanaceous ones such as potato ( Solanum tuberosum L.), tomato ( Solanum lycopersicum L.), tobacco ( Nicotiana tabacum L.), pepper ( Capsicum spp.), and eggplant ( Solanum melongena L.). Thus, not only does var. carolinense need to be controlled in fields and pastures as a direct competitor, but also it needs to be managed in adjacent areas in order to limit its ability to serve as a host. Some of the important phytophagous insect pests that use it as a host include Colorado potato beetle [ Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say)], false Colorado potato beetle [ Leptinotarsa juncta (Germar)], eggplant lacebug [ Gargaphia solani (Heidemann)], potato stalk borer [ Trichobaris trinotata (Say)], eggplant flea beetle [ Epitrix fuscula (Crotch)], potato flea beetle [ Epitrix cucumeris (Harris)], tobacco hornworm [ Manduca sexta (Haworth)], pepper maggot [ Zonosemata electa (Say)], yellowstriped armyworm [ Spodoptera ornithogalli (Guenée)], eggplant leafminer [ Tildenia inconspicuella (Murtfeldt)], potato tuberworm [ Phthorimaea operculella ( Zeller)], pepper weevil [ Anthonomus eugenii (Cano)], potato psyllid Paratrioza cacherelli (Sulc.)], and eggplant tortoise beetle [ Gratiana pallidula (Boheman)] ( Somes 1916; Anderson and Walker 1937; Foott 1968; Bassett and Munro 1986; Hare and Kennedy 1986; Wise and Sacchi 1996; Capinera 2001; Kariyat et al. 2013). The species also acts as a host reservoir to viral and fungal pathogens, including tobacco mosaic virus, tobacco vein mottling virus, tobacco etch virus, peach rosette mosaic virus, cucumber mosaic virus, tomato leafspot fungus ( Septoria lycopersici Speg.), and early blight of tomato [ Alternaria solani (Ell. & G. Martin) Sor.]; Pritchard and Porte 1921; Ellis 1971; Ramsdell and Myers 1978; Natsuaki et al. 1992; Blancard 2012; Goyal et al. 2012).

Reproductive Biology — Solanum carolinense var. carolinense is a weakly andromonoecious species with a system of selfincompatibility, and several studies have investigated the ecology, evolution, and biochemistry of its reproductive biology. The developmentally terminal and indeterminate inflorescence develops acropetally and produces variable numbers of hermaphroditic flowers at the proximal end and staminate flowers at the distal end. Studies of andromonoecy in the species have shown that sex expression in the inflorescence (i.e. the ratio of hermaphroditic:staminate flowers) can be influenced by various environmental and ecological factors ( Solomon 1985; Steven et al. 1999; Wise and Cummins 2006; Wise et al. 2008; Wise and Hébert 2010), whereas others have found evidence that sex expression is a heritable trait ( Elle 1998, 1999; Elle and Meagher 2000). Other research has shown that the androecium of both hermaphroditic and staminate flowers is fully developed and produces fertile pollen ( Solomon 1985) and that the production of pollen in staminate flowers functions as a reward to attract pollinators as well as a source of pollen for other flowers ( Solomon 1987; Connolly and Anderson 2003; but see Vallejo-Marín and Rausher 2007).

While Solanum carolinense var. carolinense exhibits most traits of a weedy species, a notable exception is its system of self-incompatibility (SI), which contrasts with self-compatible breeding systems in most weedy species ( Travers et al. 2004). As with other species in the Solanaceae , S. carolinense var. carolinense has been shown to have a gametophytic SI system under control of the single S -locus gene, which regulates stigma-pollen compatibility (e.g. Richman et al. 1995; Travers et al. 2004). Studies into the SI system of Solanum carolinense var. carolinense have shown that the diversity of S -alleles is lower than in other SI species ( Richman et al. 1995), and the SI system is plastic because of variability in the strength of SI alleles ( Mena-Ali and Stephenson 2007). Even though the SI system becomes less stringent as flowers age or when there is a lack of cross pollen ( Travers et al. 2004), selfed progeny do not experience the deleterious effects of inbreeding depression, which may facilitate colonization and establishment of the species ( Mena-Ali et al. 2008; Kariyat et al. 2011)

Notes — Solanum carolinense var. carolinense is similar to both S. dimidiatum and S. perplexum based on habit and overall morphology, but it can be separated by its unbranched or rarely once-branched inflorescence (compared to a 1- to several-branched inflorescence in the other two species). It is further distinguished from S. dimidiatum by its light brown stellate hairs with 4–5(–6) lateral rays and the central ray 1(–2)-celled and longer than the lateral rays (compared to white stellate hairs with (4–)6–10 lateral rays and the central ray 1-celled and equal to or shorter than lateral rays). Solanum carolinense var. carolinense is separated from S. perplexum by its shorter prickles on the stems and leaves (up to 6.5 mm vs. up to 15 mm in S. perplexum ), its smaller leaves (up to 15 × 10 cm vs. up to 22 × 18 cm), and its smaller corollas (up to 3 cm in diameter vs. up to 4.6 cm in diameter).

Solanum carolinense var. carolinense is a Linnean name lectotypified by Knapp and Jarvis (1990). We have placed two names, S. carolinense var. pohlianum Dunal and S. pleei Dunal , in synonymy under Solanum carolinense because their types unambiguously match the lectotype specimen of S. carolinense var. carolinense . Another name, S. occidentale Dunal , has been previously treated as a synonym of S. carolinense (e.g. D’ Arcy 1974), but it is now recognized as a synonym of S. anguivi Lam. ( Solanaceae Source 2014 ). Two infraspecific names have been proposed to include only white-flowered individuals of the species, and we have also placed these in synonymy under

S. carolinense var. carolinense . White- and blue-flowered plants are commonly found in mixed populations across the entire range of S. carolinense , and we do not consider corolla color to be a useful character in delimiting an infraspecific taxon. In the protologue of S. carolinense var. albiflorum, Kuntze did not cite a type specimen. We have chosen the specimen C. E. O. Kuntze 2768 (NY) as the lectotype, which is from Kuntze’ s herbarium and is annotated with the name of the taxon in his handwriting. Dunal (1852) makes reference to a Pohl and Sendtner collection from Brazil in the protologue of S. carolinense var. pohlianum . We have located a single specimen collected in Brazil by Pohl, but because it is not possible to determine with certainty whether or not it was the same sheet Dunal used in his description, we have designated the specimen J. B. E. Pohl s. n. (M–M0171734) as a lectotype.

Selected Specimens Examined — CANADA. Ontario: Lambton County, Point Edward, 19 Aug 1902 (fl), C. K. Dodge s. n. ( SMU); Point Edward, 14 Aug 1901 (fl), J. Macoun 54532 ( NY).

U. S. A. Alabama: Houston County, near W bank of Chattahoochee River, 2 mi. NE of Chattahoochee St. Park, 10 mi. SE of Gordon, 31°02′N, 85°01′W, 10 Jul 1988 (fr), R. Burckhalter 1442 ( UNA). Arkansas: Washington County, 4 mi. S of Prairie Grove, T14N, R32W, SWSE, S1, 30 May 1977 (fl), D. Griffin I-8 ( BRIT). Connecticut: New Haven County, Mill Rock, Hamden, 28 Jun 1955 (fl), J. J. Neale s. n. ( FLAS). Delaware: N of Leipsic, 30 Jun 1949 (fl), S. C. Hood 2271 ( FLAS). District of Columbia: Near U. St., Washington, D.C., 3 Aug 1895 (fr), L. H. Dewey 316 ( MO). Florida: Wakulla County, St. Marks Nat’ l Wildlife Refuge, Wakulla Unit, S side of Northline Rd., at second crossing, ca. 1.5 mi. WSW of Wakulla Beach Rd., 30.13884 N, 84.27885 W, 12 Jun 2007 (fl), L. C. Anderson 23179 ( FSU). Georgia: Toombs County, ca. 1 mi. E of Vidalia on US 280, 32°12′N, 82°25′W, 18 May 1976 (fl), J. C. Solomon 5559 ( MO). Idaho: Canyon County, New Plymouth, 670 m, 10 Sep 1910 (fr), J. F. Macbride 732 (P). Illinois: Tazewell County, near 10 Mile Creek, 8 Sep 1951 (fl), V. H. Chase 12158 ( BRIT). Indiana: Porter County, US 30, ca. 4 mi. E of Valparaiso, 4 Jul 1961 (fl), N. C. Henderson 61–543 ( FSU). Iowa: Story County, just N of Iowa State University and Squaw Creek, R24W, T84N, 13 Jul 1969 (fl), G. Davidse 1788 ( MO). Kansas: Morris County, Bridwell Ranch, 8 mi. S and 1 mi. E of Council Grove, 20 Jun 1966 (fl), D. E. Dallas 12 ( VDB). Kentucky: Madison County, Fort Boonesborough State Park, SW of jct. of Ky. 627 and the Kentucky River, 25 Jun 1992 (fl, fr), J. R. Abbott et al. 2691 ( FLAS). Louisiana: Ouachita Parish, W of LA 557 between Cypress Creek and Caldwell Parish line, SW of Luna, T15N, R2E, S15, 6 May 1986 (fl), R. D. Thomas 95925 ( BRIT, FLAS, NY). Maryland: Howard County, Rt. 94, 1.5 mi. S of Lisbon, 19 Sep 1966 (fl), C. F. Reed 80284 ( MO). Massachusetts: Middlesex County, center of Cambridge, vicinity of Harvard University, 7 Jul 1975 (fl), H. E. Ahles 80522 ( SMU). Michigan: Cass County, Howard Twp., T7S, R16W, S16, 25 Jul 1950 (fl), G. W. Parmelee 1610 ( VDB). Mississippi: Washington County, NE of Stoneville, Delta Experimental Forest, T19N, R7W, S33, 29 May 1987 (fl), C. T. Bryson 5832 ( BRIT). Missouri: Lincoln County, ca. ½ mi. N of Big Creek, dirt road W of MO 61, 10 Aug 1978 (fl), W. G. D’ Arcy 1061 ( FSU). New Jersey: Cumberland County, Stow Creek Twp., Gum Tree Corner, N of Gum Tree Corner Wildlife Management Area, Canton quadrangle, 4 Aug 2004 (fl), G. Moore 6686 ( VDB). New Mexico: Doña Ana County, Las Cruces, New Mexico State University, Frenger Mall between Foster Hall and Science Hall, 1219 m, 9 Oct 2002 (fl), R. W. Spellenberg s. n. ( BRIT, NMC-n.v.). New York: Stewart Park, Ithaca, 1 Aug 1933 (fl, fr), G. Wakeman-Bonne s. n. (P). North Carolina : Carteret County, ca. 2 mi. NW of Beaufort, 29 Aug 1952 (fl), H. L. Blomquist 15697 ( VDB). Ohio: Delaware County, below Stratford, 15 Sep 1928 (fr), R. Crane 3223 ( FSU). Oklahoma: Creek County, Deep Fork Wildlife Management Area, T14N, R9E, S28, 23 Jun 1998 (fl), D. Benesh et al. DFX254 ( BRIT). Pennsylvania: Bedford County, 1.5 mi. E of West End, 5 Aug 1970 (fl), H. Duppstadt & D. Duppstadt 2833 ( BRIT, FLAS, NY, UNA, VDB). South Carolina : Pickens County, by US 178, 0.6 mi. N of South Carolina Hwy 11, 25 May 1972 (fl), J. L. Collins 553 ( VDB). Tennessee: Anderson County, 20,500 ft. N, 65,150 ft. E, Corp of Engineer Map, 1959, 10 Jun 1961 (fl), W. H. Ellis 28609 ( FSU). Texas: Van Zandt County, 1.5 mi. SW of Van, on Hwy. 20 frontage road at exit 450, 32°30′32″N, 95°39′18″W, 147 m, 20 May 2012 (fl), G. A. Wahlert 144 ( BRIT, MO, NY, UT). Virginia: Isle of Wight County, behind cemetery of Mill Swamp Baptist Church, St. Rts. 621 & 623, ca. 3.8 mi. N of Raynor, 8 Jun 1989 (fl) G. M. Plunkett 295 ( BRIT). West Virginia: Wetzel County, near Littleton, 26 Jul 1972 (fl), O. E. Haught 7302 ( VDB); between Hot Springs and White Sulphur Springs, 3 Jul 1938 (fl), G. Wakeman-Bonne s. n. (P). Wisconsin: Vernon County, Island 8, Mississippi River, mi. 688.4, T14N, R7W, S18, large island E side of main channel, 636 m, 3 Jul 1975 (fl), S. R. Ziegler & M. F. Leykom 1581 ( BRIT).

| NY |

William and Lynda Steere Herbarium of the New York Botanical Garden |

| SMU |

Sangmiung University |

| UNA |

University of Alabama Herbarium |

| BRIT |

Botanical Research Institute of Texas |

| FLAS |

Florida Museum of Natural History, Herbarium |

| MO |

Missouri Botanical Garden |

| FSU |

Jena Microbial Resource Collection |

| VDB |

Vanderbilt University |

| UT |

University of Tehran |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Solanum carolinense var. carolinense

| Wahlert, Gregory A., Chiarini, Franco E. & Bohs, Lynn 2015 |

Solanum carolinense

| Benke 1939: 213 |

Solanum carolinense var. albiflorum

| Kuntze, Revis. Gen. Pl. 1891: 454 |

Solanum carolinense var. pohlianum

| Dunal 1852: 305 |

Solanum pleei

| Dunal 1852: 305 |