Melayonchis eloisae Dayrat, 2017

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1080/00222933.2017.1347297 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:671922DB-C6C1-44A5-B2CD-A3A3127CB668 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EBF93DF3-439F-4180-9F03-C514D5BF9568 |

|

taxon LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:act:EBF93DF3-439F-4180-9F03-C514D5BF9568 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Melayonchis eloisae Dayrat |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Melayonchis eloisae Dayrat View in CoL sp. nov.

( Figures 3–8 View Figure 3 View Figure 4 View Figure 5 View Figure 6 View Figure 7 View Figure 8 )

Type locality

Singapore, Pasir Park , 01°22.840 N, 103° 57.224 E 1 April 2010 [station 5, mangrove forest with rich litter, lobster mounds, dead logs] GoogleMaps . By definition, the type locality is the locality of the holotype, but the paratype is also from the same locality GoogleMaps .

Type material

Holotype: 95% alcohol [DNA 1011], 15/ 10 mm. One paratype: formalin, 22/ 13 mm. The holotype and the paratype are both designated here, leg. B. Dayrat and S.K. Tan ( ZRC. MOL.6499).

Additional material examined

India, Andaman Islands, Middle Andaman, Rangat, Shyamkund, 12°28.953 ʹ N, 092°50.638 ʹ E, 11 January 2011, 4 specimens (17/12 [DNA 1097] to 7/ 5 mm), leg. B. Dayrat and V. Bhave [station 57, by a large river, deep mangrove with tall trees, small creeks, and plenty of dead muddy logs, next to a road and a small cemented bridge for creek] ( BNHS 49); India, Andaman Islands, South Andaman, Bamboo Flat, Shoal Bay, 11°47.531 ʹ N, 092°42.577 ʹ E, 13 January 2011, 9 specimens (22/12 to 5/ 3 mm), leg. B. Dayrat and V. Bhave [station 59, open mangrove with medium trees, hard mud, dead logs, next to a road and a small cemented bridge for creek] ( BNHS 51); Singapore, Lim Chu Kang, 01°26.785 ʹ N, 103° 42.531 ʹ E, 5 April 2010, 1 specimen (21/12 [DNA 1003] mm), leg. B. Dayrat and S.K. Tan [station 9, mangrove east of the jetty; open forest with medium trees and medium mud; ended on sun-exposed mudflat outside the mangrove with soft mud; very polluted with trash] ( ZRC.MOL.6500). Malaysia, Peninsular Malaysia, Merbok, 05°39.035 ʹ N, 100°25.782 ʹ E, 12 July 2011, 31 specimens (22/12 [#1] to 5/ 3 mm; 20/13 [#2], 10/7 [#3], 10/8 [DNA 951] mm), leg. B. Dayrat and T. Goulding [station 21, deep Rhizophora forest with old, tall trees, hard mud, many small creeks and many dead logs] ( USMMC 00007); Malaysia, Peninsular Malaysia, Merbok, 05°40.143 ʹ N, 100°26.178 ʹ E, 12 July 2011, 3 specimens (22/14 to 12/ 10 mm), leg. B. Dayrat and T. Goulding [station 22, mostly Rhizophora , soft mud and some very soft mud near creek] ( USMMC 00008); Malaysia, Peninsular Malaysia, Kuala Sepatang, 04°50.434 N, 100°38.176 E, 18 July 2011, 8 specimens (23/14 to 7/ 6 mm; 12/10 [DNA 922] mm), leg. B. Dayrat and T. Goulding [station 27, old forest with old, tall Rhizophora trees, high in the tidal zone (ferns), following boardwalk in educational preserve, reached a creek lower in the tidal zone, with mud] ( USMMC 00009); Malaysia, Peninsular Malaysia, Matang, off Kuala Sepatang, Crocodile River, Sungai Babi Manpus, 04°49.097 ʹ N, 100°37.370 ʹ E, 19 July 2011, 3 specimens (19/10 to 6/ 5 mm), leg. B. Dayrat and T. Goulding [station 28, old and open Rhizophora forest with tall trees, hard mud, creeks, and many dead logs] ( USMMC 00010); Malaysia, Peninsular Malaysia, Matang, close to the jetty, facing the fishermen’ s village on the other side of the river, 04°50.154 ʹ N, 100°36.368 ʹ E, 20 July 2011, 6 specimens (21/15 to 8/ 6 mm), leg. B. Dayrat and T. Goulding [station 29; oldest and open Rhizophora forest of tallest and beautiful trees, with hard mud, many creeks and many dead logs] ( USMMC 00011); Brunei Darussalam, Mentiri, Jalan Batu Marang, 04°59.131 N, 115°01.820 E, 29 July 2011, 67 specimens (24/12 [#1] to 6/ 5 mm; 7/5 [DNA 1043] mm), leg. B. Dayrat, T. Goulding and S. Calloway [station 34, old mangrove with tall Rhizophora trees with high roots and Thalassina mounds] ( BDMNH); Vietnam, Can Gio, 10°27.803 ʹ N, 106°53.288 ʹ E, 16 July 2015, 4 specimens (20/12 to 7/ 5 mm; 13/8 [DNA 5607]), leg. T. and J. Goulding [station 228, high intertidal, open forest of tall Rhizophora trees, hard mud not deep, near a small river] ( ITBZC IM 00009).

Distribution

Singapore (type locality), India ( Andaman Islands ), Peninsular Malaysia (Strait of Malacca), Brunei Darussalam, Vietnam .

Etymology

Melayonchis eloisae is dedicated to Eloïse Dayrat, for the time that her father (the first author) has to spend away from her, exploring mangroves and missing her.

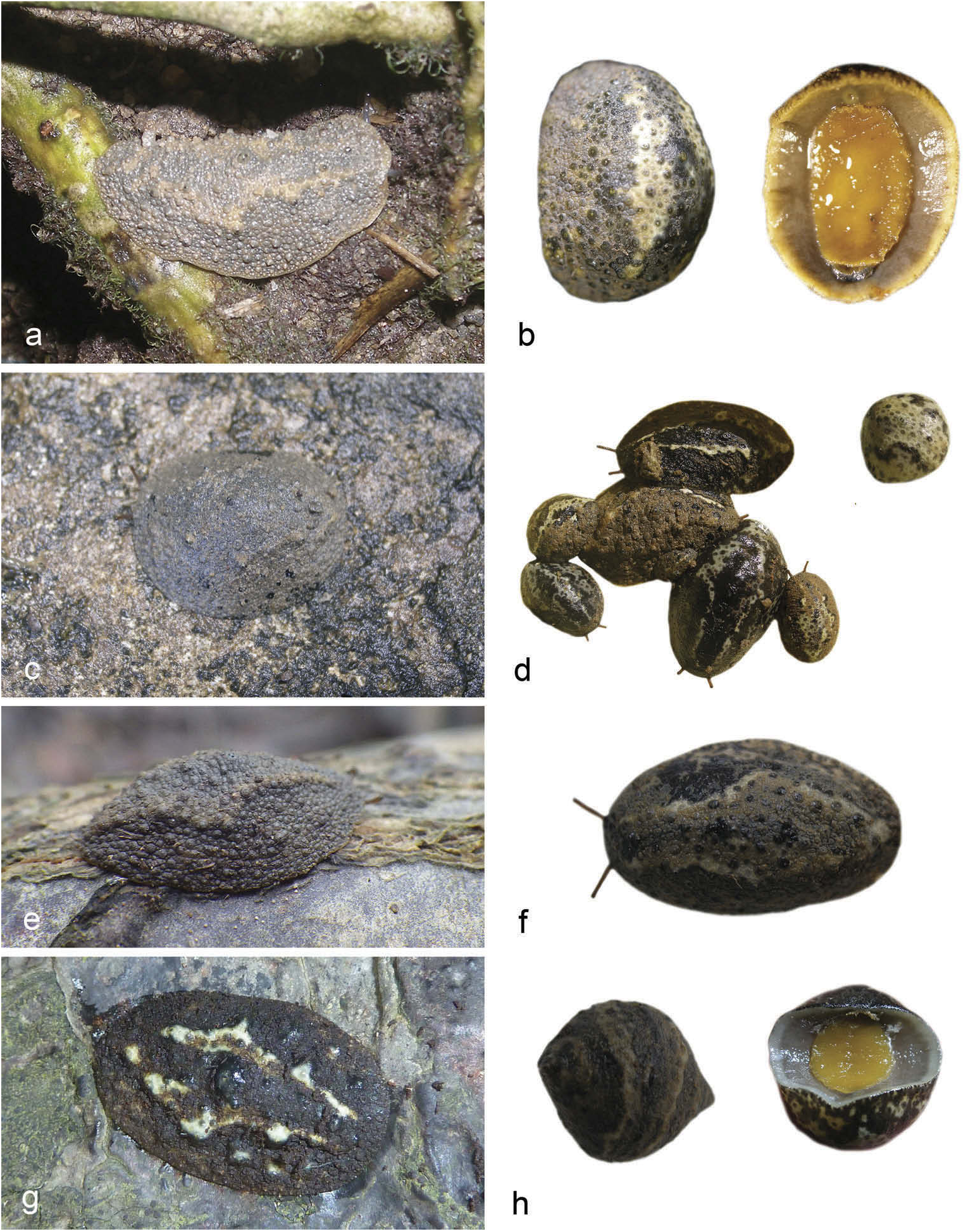

Habitat ( Figure 3 View Figure 3 )

Melayonchis eloisae is mostly found in the high intertidal, and it especially favours old Rhizophora forests with Thalassina mounds. It lives on trunks and roots of mangrove trees, often not muddy but covered with algae instead. It can also be found on dead logs and even, occasionally, on cemented walls (of bridges or ditches near mangroves). It is not found directly on mud.

Abundance

In the right habitat, M. eloisae can be abundant (for instance, we found dozens of specimens in Brunei). However, even when the habitat seems perfect for it, one may not find it or may find just a few individuals. So, unlike some species of Platevindex which are almost always found, one cannot really predict whether M. eloisae will be found.

Colour and morphology of live animals ( Figure 4 View Figure 4 )

Even though they are not found directly on mud, live animals are covered dorsally with a thin layer of muddy mucus, and the colour of their dorsal notum can hardly be seen. That thin layer of mucus makes them very cryptic. It may also help prevent desiccation. The colour of the dorsal notum appears after the thin muddy layer is removed. The background of the notum is usually black or dark brown, but it can exceptionally be light brown. The background is mottled by white areas. Most typically, those white areas form two irregular longitudinal lines, one either side of the central axis. Additional, irregular white areas can exist as well. The colour of the hyponotum varies between light greyish and dark brown but is always marked by a significantly lighter ring at its margin. The foot is orange, occasionally yellow. The ocular tentacles are short and extend for only a few millimetres beyond the notum margin when the animal is crawling undisturbed. The head is small and remains covered by the dorsal notum as the animal crawls. The body is not flattened. The dorsal notum is elongated, oval. The dorsal notum is thick. Its surface, when the animal is undisturbed, is not smooth. Dorsal gills are absent. Large papillae are absent but small conical papillae are present. About 10 of those papillae bear a black ‘dorsal eye’. A larger, central papilla bears three black ‘dorsal eyes’. In addition, the notum is finely granular. When the animal is disturbed (typically, if one touches its dorsum), it forms an almost perfect sphere, with a smooth dorsal notum. In fact, in the field, we called this species ‘black and white small ball’. Animals that are preserved without first being relaxed remain coiled up in a sphere. Crawling individuals can measure up to 25 mm, but most of them measure about 15 mm on average.

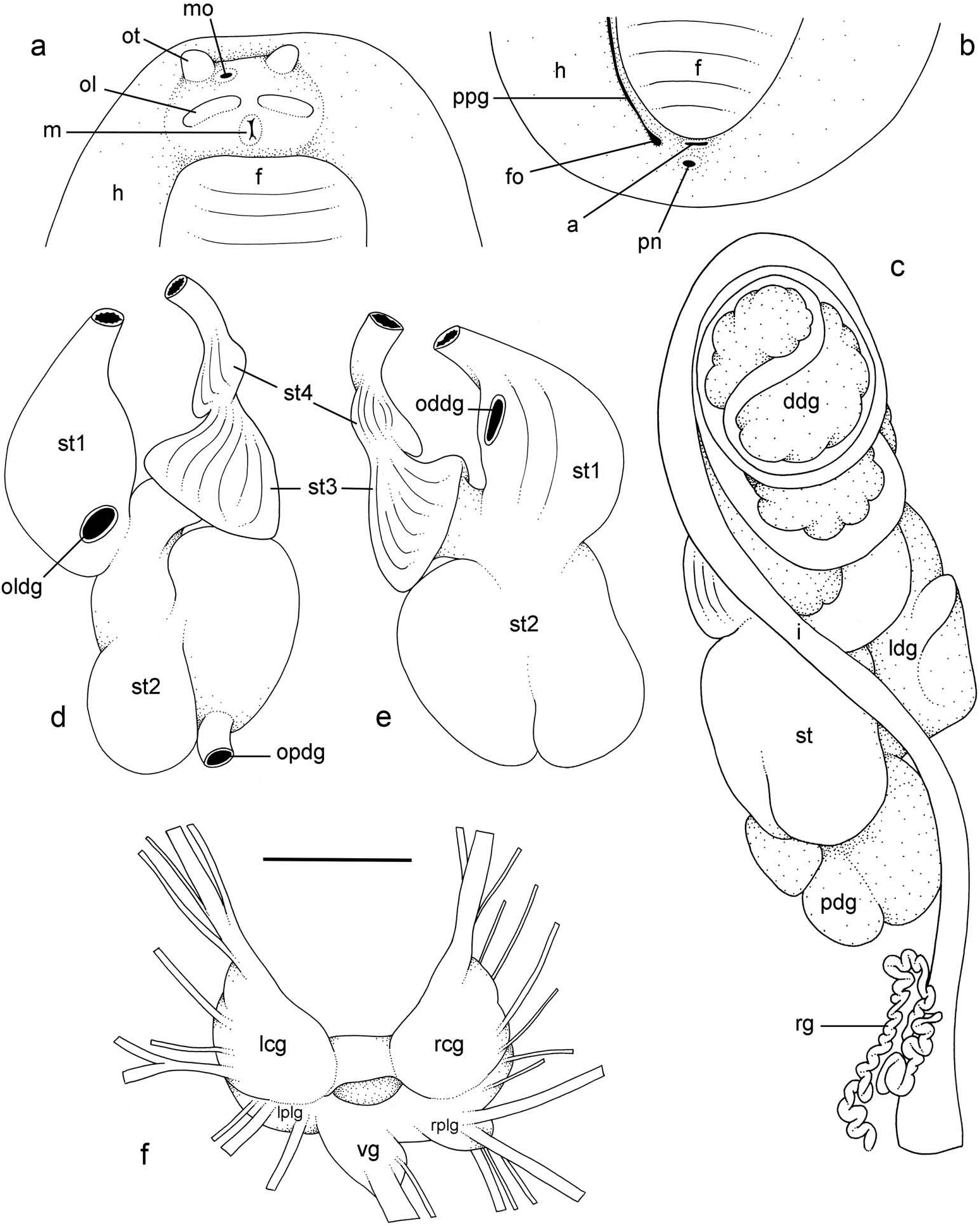

External morphology ( Figure 5a, b View Figure 5 )

Preserved specimens no longer display the distinct colour traits of live animals. The ventral colour, in particular, is homogeneously whitish or creamish. The width of the hyponotum relative to the width of the pedal sole varies among individuals and ranges from about 1/3 to 3/5 of the total width (in ventral view). The anus is posterior, median and close to the edge of the pedal sole ( Figure 5a View Figure 5 ). On the right side (to the left in ventral view), a peripodial groove is present at the junction between the pedal sole and the hyponotum, running longitudinally from the buccal area to the posterior end, a few millimetres from the anus and the pneumostome ( Figure 5b View Figure 5 ). The pneumostome is median. Its position on the hyponotum relative to the notum margin and the edge of the pedal sole varies among individuals but averages in the middle. The position of the female pore (at the posterior end of the peripodial groove) does not vary much among individuals ( Figure 5b View Figure 5 ). In the anterior region, the left and right ocular tentacles are superior to the mouth. They are outside the body if specimens were relaxed before preservation; otherwise, they are retracted. Eyes are at the tip of the ocular tentacles. Inferior to the ocular tentacles, superior to the mouth, the head bears a pair of oral lobes. On each oral lobe there is an elongated bump, likely with sensitive receptors. The male aperture (opening of the copulatory complex) is located below the right ocular tentacle, slightly to its left (internal) side ( Figure 5a View Figure 5 ).

Visceral cavity and pallial complex

Marginal glands (found in Onchidella ) are absent. The anterior pedal gland is oval and flattened, lying free on the floor of the visceral cavity below the buccal mass. The visceral cavity is not pigmented internally and not divided (the heart is not separated from the

visceral organs by a thick, muscular membrane). The heart, enclosed in the pericardium, is on the right side of the visceral cavity, slightly posterior to the middle. The ventricle, anterior, gives an anterior vessel supporting several anterior organs such as the buccal mass, the nervous system and the copulatory complex. The auricle is posterior. The kidney is more or less symmetrical, the right and left parts being equally developed. Occasionally, the right part is slightly longer than the left part. The kidney is intricately attached to the respiratory complex. The lung is in two left and right, equally developed, more or less symmetrical parts. Occasionally, the right part is slightly longer than the left part.

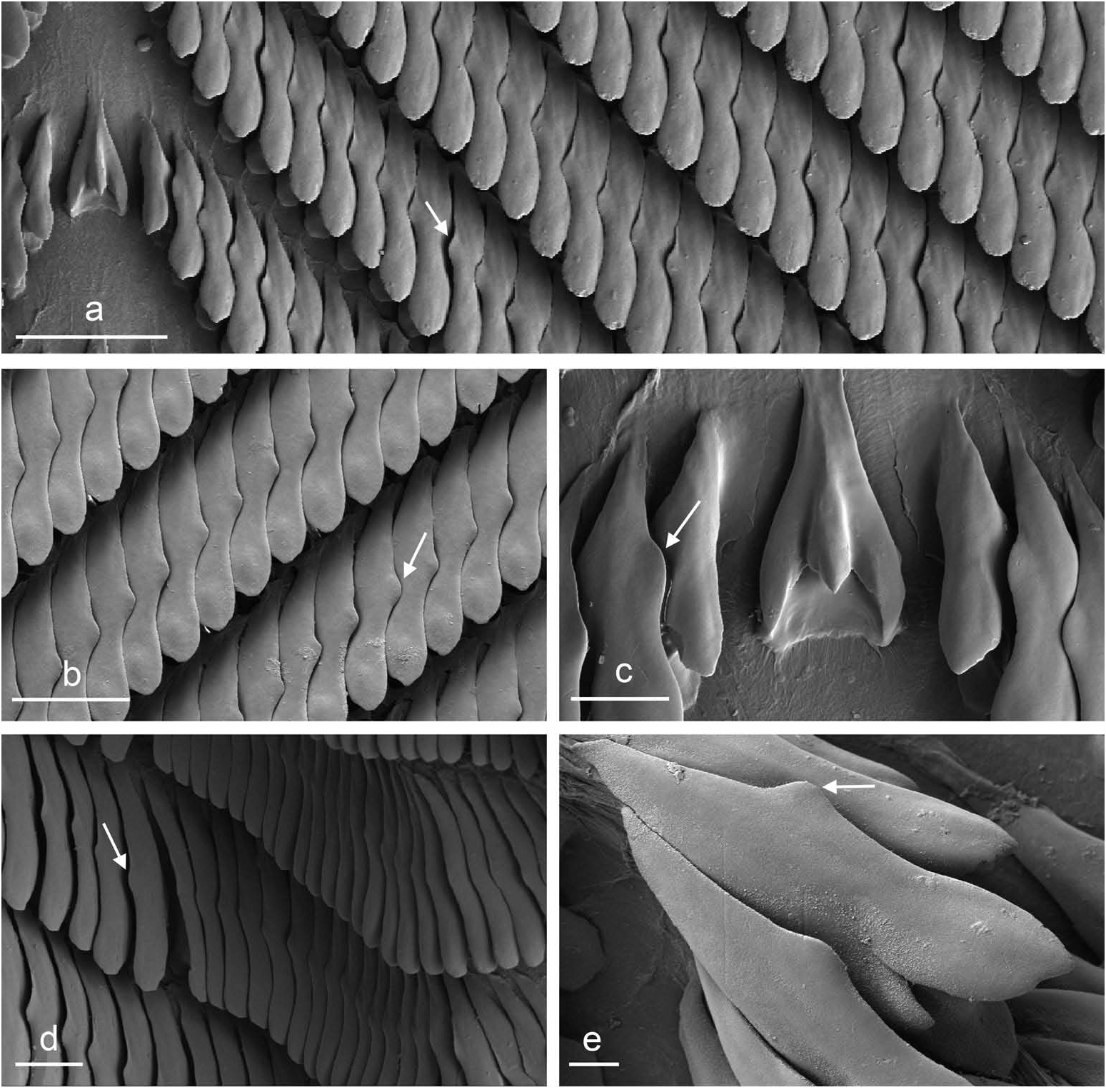

Digestive system ( Figures 5c–e View Figure 5 , 6 View Figure 6 )

There are no jaws. The left and right salivary glands, heavily branched, join the buccal mass dorsally, on either side of the esophagus. The radula is between two large postero-lateral muscular masses. Each radular row contains a rachidian tooth and two half rows of lateral teeth. Examples of radular formulae are: 66 × (110–1–110) in BDMNH station 34 #1 (24 mm long), 55 × (110–1–110) in USMMC 00007 #1 (22 mm long), 65 × (95–1–95) in USMMC 00007 #2 (20 mm long), and 45 × (75–1–75) in USMMC 00007 #3 (10 mm long). The rachidian teeth are unicuspid: the median cusp is always present; there are no distinct lateral cusps on the lateral sides of the base of the rachidian tooth ( Figure 6 View Figure 6 ). The length of the rachidian teeth is about 30 µm, significantly less than the length of the lateral teeth. The lateral aspect of the base of the rachidian teeth is straight (not concave). The half rows of lateral teeth form an angle of 45° with the rachidian axis. Along a half row, all the lateral teeth do not have exactly the same length and shape. The lateral teeth seem to be unicuspid with a flattened and curved hook, but there also is an outer pointed spine on the lateral expansion of the base. In most cases, the basal lateral spine cannot be observed because it is hidden below the hook of the next, outer lateral tooth. It can only be observed when the teeth are not too close or when teeth are placed in an unusual position. The length of the hook of the lateral teeth gradually increases (from innermost to outermost) from about 40–50 µm to 60–70 µm, excluding the first few (about 5) innermost and outermost lateral teeth which are significantly smaller than the rest of the lateral teeth. The inner lateral aspect of the hook of the lateral teeth is not straight. It is marked by a strong protuberance placed over the preceding adjacent tooth. This protuberance diminishes gradually and is inconspicuous in the outermost teeth (of which, as a result, the lateral aspect is almost straight). The outermost teeth are much closer to one another than the innermost teeth and, as a result, seem narrower. Finally, the tip of the hook gradually changes from pointed to round from the innermost to outermost teeth.

The esophagus is narrow and straight, with thin internal folds. The esophagus enters the stomach anteriorly ( Figure 5d, e View Figure 5 ). Only a portion of the posterior aspect of the stomach can be seen in dorsal view because it is partly covered by the lobes of the digestive gland ( Figure 5c View Figure 5 ). The dorsal lobe is mainly on the right. The left, lateral lobe is mainly ventral. The posterior lobe covers the posterior aspect of the stomach. The stomach is a U-shaped sac divided into four chambers ( Figure 5d, e View Figure 5 ). The first chamber, which receives the esophagus, is delimited by a thin layer of tissue, and receives the ducts of the dorsal and lateral lobes of the digestive gland. The second chamber, posterior, is delimited by a thick muscular tissue and receives the duct of the posterior lobe of the digestive gland. It appears divided externally but consists of only one internal chamber. The third, funnel-shaped chamber is delimited by a thin layer of tissue with high ridges internally. The fourth chamber is continuous and externally similar to the third, but it bears only low, thin ridges internally. The intestine is long and narrow ( Figure 5c View Figure 5 ). The pattern of its loops is intermediary between types II and III. A rectal gland is present ( Figure 5c View Figure 5 ). It is a long, narrow and coiled tube that opens in the left portion of the pulmonary complex. Its function is unknown.

Nervous system ( Figure 5f View Figure 5 )

The circum-esophageal nerve ring is post-pharyngeal and pre-esophageal. The cerebral commissure between the two cerebral ganglia is short but its length does vary among individuals. Pleural and pedal ganglia are also all distinct. The visceral commissure is short but distinctly present and the visceral ganglion is more or less median. Cerebropleural and pleuro-pedal connectives are very short and pleural and cerebral ganglia touch each other. Nerves from the cerebral ganglia innervate the buccal area and the ocular tentacles, and, on the right side, the penial complex. Nerves from the pedal ganglia innervate the foot. Nerves from the pleural ganglia innervate the lateral and dorsal regions of the mantle. Nerves from the visceral ganglia innervate the visceral organs.

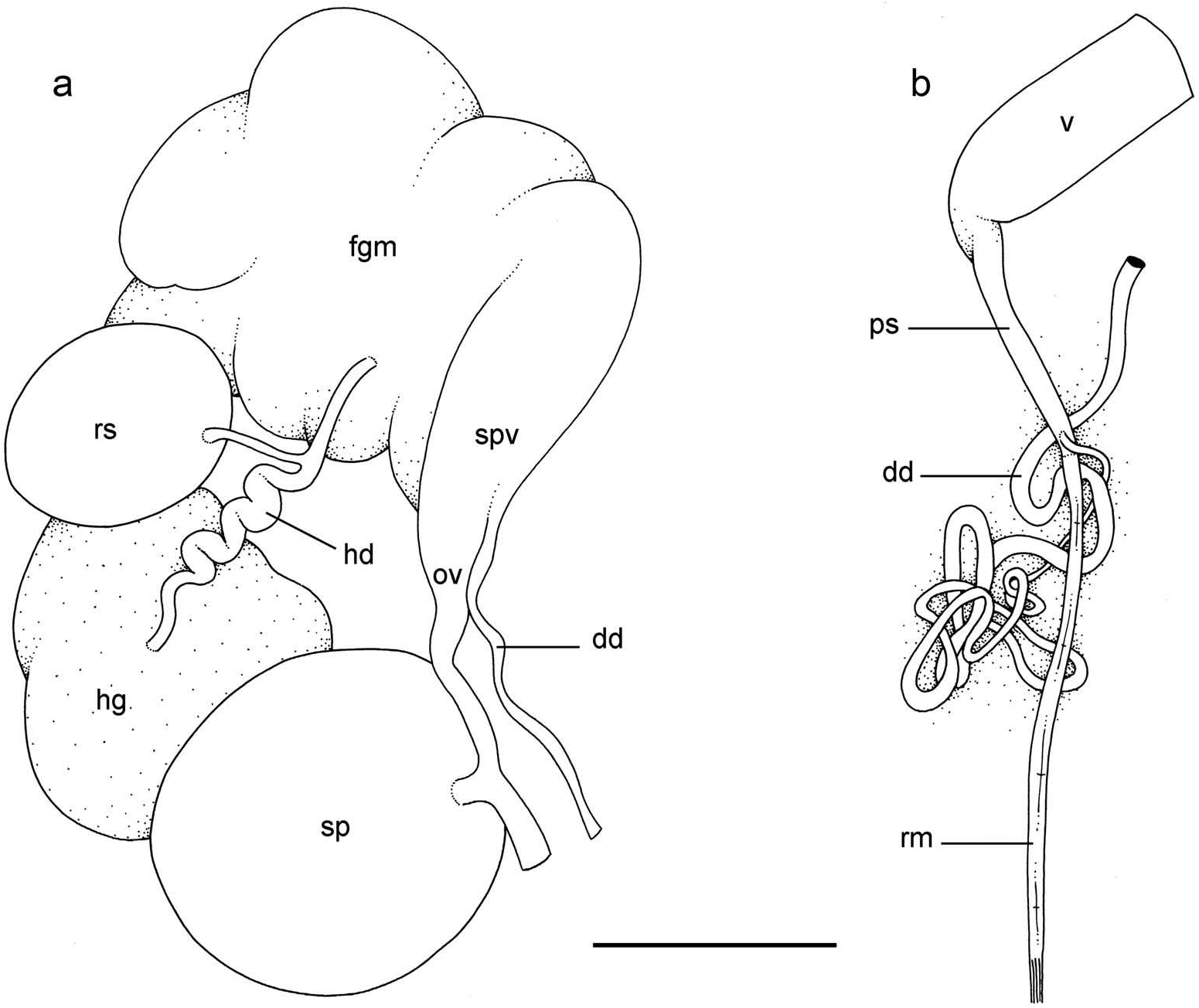

Reproductive system ( Figure 7a View Figure 7 )

Sexual maturity is correlated with animal length. Mature individuals have large female organs (with a large female gland mass) and fully developed,anterior male copulatory parts. Immature individuals may have inconspicuous female organs (or simply none) and rudimentary anterior male parts. The hermaphroditic gland is a single mass, joining the spermoviduct through the hermaphroditic duct (which conveys the eggs and the autosperm). There is a large and approximately spherical receptaculum seminalis (caecum) along the hermaphroditic duct. The female gland mass contains various glands (mucous and albumin) which can hardly be separated by dissection and of which the exact connections remain uncertain. The hermaphroditic duct becomes the spermoviduct (which conveys eggs, exosperm and autosperm) which is not divided proximally, at least not externally. The spermoviduct is embedded within the female gland mass, at least proximally. Distally, the spermoviduct branches into the deferent duct (which conveys the autosperm up to the anterior region, running through the body wall) and the oviduct. The free oviduct conveys the eggs up to the female opening and the exosperm from the female opening up to the fertilisation chamber, which should be near the proximal end of the spermoviduct. The spermatheca (for the storage of exosperm) is nearly spherical and connects to the oviduct through a very short duct. The oviduct is narrow and straight. The vaginal gland is absent.

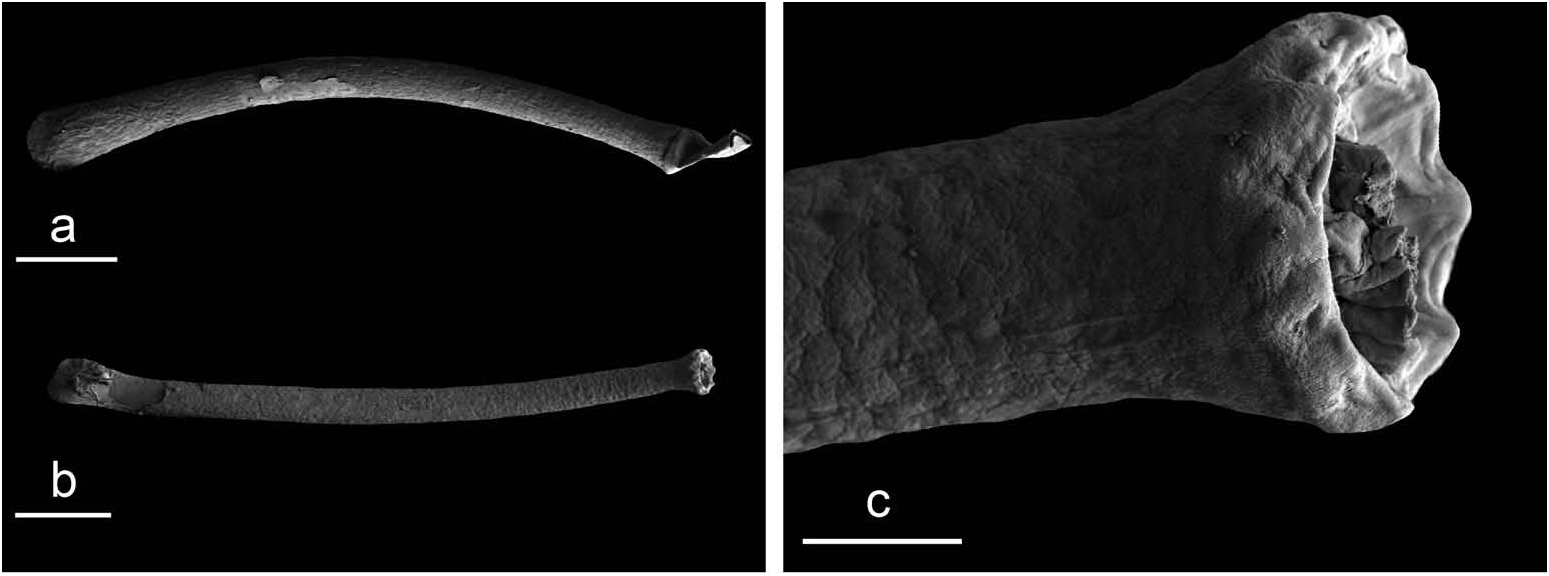

Copulatory apparatus ( Figures 7b View Figure 7 , 8 View Figure 8 )

The male anterior organs consist of the penis, penial sheath, vestibule, deferent duct and retractor muscle ( Figure 7b View Figure 7 ). There is no penial accessory gland. The penial sheath is short (less than 2 mm in length) and straight. The penial sheath protects a penis which consists of a short, elongated and slightly curved tube, about 0.7 mm long and 35 μm in diameter ( Figure 8 View Figure 8 ). There are no penial hooks. The vestibule is approximately as long as the penial sheath, but much larger ( Figure 7b View Figure 7 ). The insertion of the retractor muscle marks the separation between the penial sheath and the deferent duct ( Figure 7b View Figure 7 ). The retractor muscle is much longer than the penial sheath and inserts at about half the length of the visceral cavity. The deferent duct also is highly convoluted with many loops (in immature specimens, the deferent duct is significantly less convoluted).

Distinctive field diagnostic features

A table at the end of the introduction summarises the most important features that can help distinguish and identify Melayonchis species ( Table 3). In the field, individuals of M. eloisae can easily be recognised because they coil up into a sphere when disturbed. The presence of an orange foot and a notum with a black background and two longitudinal, irregular, white lines can also help identify live specimens in the field (even though the dorsal colour pattern does vary among individuals and the two white lines are not always present). When animals are observed without being disturbed while crawling and still covered with a thin layer of muddy mucus, then they are much harder to identify.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |